Why do we box? It’s an almost ludicrously inefficient form of combat. The last thing the SAS suggests its soldiers to do is put their dooks up. But boxing is nonetheless the world’s leading combat sport — millions watch boxing in lockdown, and when we’re all allowed out, thousands will head first to the pub, then out into the streets and carparks, to throw punches at each other’s heads. Why?

I have the answer. It came to me by a combination of Joanna Lumley and a fight I once witnessed between cobras.

Boxing is not a great form of combat — not if your aim is to put your opponent out of action fast. But Joanna, visiting a boxing gym in Cuba for a recent television programme, made a crucial point: ‘It’s the most natural thing in the world — you put your fists up.’ She was right.

There are Sumerian images of boxing 5,000 years old. Evidence for boxing has been found in ancient Babylon and on Egyptian papyrus. Boxing was part of the Olympic Games in 688 bc. What’s more, when Voulters fought Hassett in the battle of 2Ex at Emanuel School, they put their fists up. When my neighbour Ah-Chuen on Lamma Island, Hong Kong, took exception to a visiting Japanese engineer, he conveyed his reproof with swinging fists. It’s what people do. It seems not to vary from culture to culture: it’s a human thing.

Boxing hurts the hands too much to carry on for long, but it’s quite good at sorting out the winner from the loser

If you want to win a fight, the default ploy is to kick your opponent in the balls and perhaps then in the head. Saves untold trouble. But boxers don’t do that, because it’s against the rules, and bar-room fighters tend not to either, because there seems to be a power-ful inhibition that stops them.

So people swing punches at heads, and the problem is that unless you’re wearing boxing gloves it hurts: hitting bone against bone isn’t smart. Ben Stokes, the England cricketer, broke his wrist punching a locker after he was out first ball, and had to miss the World T20 championship. Later he was in trouble for a street fight, over-zealously protecting a gay couple — demonstrating that it hurts less when your fists are anaesthetised by alcohol. The pain in the aggressor’s hands acts as a safety measure.

Padded gloves were introduced into boxing by the Marquess of Queensberry in 1867. They don’t protect boxers from the savagery of bare-knuckle fighting; they protect their hands so they can land serious concussive blows in comparative comfort. Boxing is a highly specialised form of combat: a limited target and fists that don’t hurt.

So let’s get to those cobras.

The most efficient way for a cobra to win a fight is obvious: after all, they are armed with large fangs that inject lethal venom. But the two male snakes I saw fighting in Sri Lanka weren’t trying to bite each other. Instead they were wrapped round each other like a stick of barley sugar, and were trying to bear each other to the ground.

Lethal creatures choosing a non-lethal form of combat… it’s a pattern you can find repeated again and again. Impala rams don’t try to gore each other’s entrails out, they lock horns. Humpback whales posture at each other. Birds sing. Many primate species fight and make up again, as explained in Frans de Waal’s classic work of ethology, Peace-making Among Primates, in which he contends that the reconciliations are more important than the combat.

Lethal combat is far from unknown in many species, but generally speaking it’s the last resort, and happens when two equal males can’t resolve a dispute any other way. As a generalisation, combat is a genuine test of skill, strength and experience, but lives are not often at risk. Ritual predominates over lethal danger.

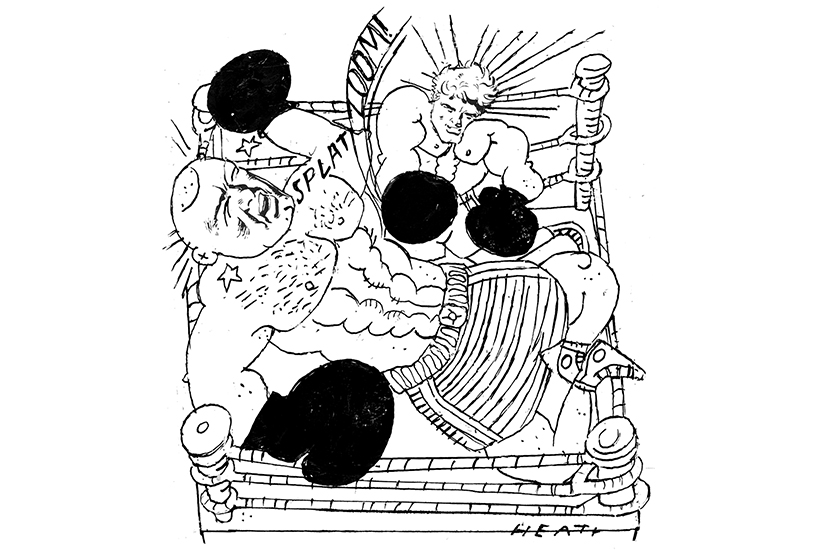

And that is why humans box. Boxing is not efficient: but it’s not supposed to be efficient. The whole idea is that it’s inefficient. It hurts the hands too much to carry on for long, but it’s quite good at sorting out the winner from the loser. As a bonus, the loser carries the marks of combat for a good week or so afterwards: black eyes, swollen noses, cut lips, red ears: an advertisement of his opponent’s enhanced or retained status — hence the ancient jest: ‘You should see the other guy.’

More dangerous forms of combat are mostly rejected. People sometimes get dangerously carried away with a fallen opponent, but in the main, a punch-up is an effective way of setting a dispute with minimal damage. It hurts and humiliates, sure, but both parties walk away. In Nevil Shute’s novel The Chequer Board, Corporal Duggie Brent is a commando who takes his combat training into a pub. He has lost his appreciation of pub-fight etiquette, unintentionally kills his man and is tried for murder. Murder is not supposed to happen in a pub fight.

I had always assumed that the fist–fighting convention came from watching boxing, or from watching films in which characters throw massive punches without sustaining so much as a sore knuckle. But where did boxers or film-makers get their ideas from? The fact is that fist-fighting is an archetypal form of combat. It’s the way people fight when they’re not fighting for their lives. In normal circumstances, when people fight for honour or precedence or access to females, they put their fists up — and afterwards, though the winner is a good deal happier than the loser, they carry on living and breathing, as cobras do.

Comments