Since becoming Labour leader, Keir Starmer has single-mindedly been trying to persuade red wall voters that Labour is ‘patriotic’, just like them. He thereby hopes to clear away those cultural barriers that have arisen between Labour in the north and midlands where voting for the party used to be almost instinctive. As he said in his first leader’s speech back in September, Starmer wants red wall voters to ‘take another look’ at Labour now it is under his leadership: he wants to show them that it is no longer the party of Jeremy Corbyn and his supporters.

But many in his party don’t like what Starmer is doing, because a significant number of Labour members — being middle class and university-educated — are not just like red wall voters. At the moment the party is arguing over Starmer’s use of the Union flag but this is a disagreement that goes deeper than which adornment the Labour leader should stand next to when making a speech. It is, for some Labour members, an existential matter.

If the recent past is any guide, Starmer will have an uphill battle to persuade members of the virtues of his strategy. For, even before Corbyn became leader, Labour members were arguing, not over a flag, but a mug.

During his ill-fated leadership, Ed Miliband struggled with the same issue now faced by Starmer

During his ill-fated leadership, Ed Miliband struggled with the same issue now faced by Starmer: once habitual Labour voters in what used to be called the ‘traditional’ working-class were drifting into the hands of Ukip. The ostensible reason was immigration, then seen by 45 per cent of voters as the most important issue facing Britain. But beneath that was the sense — especially in those parts of England yet to be described as the ‘red wall’ — that Labour no longer represented ordinary working people. Miliband did his best to rebuild a connection, speaking of a ‘British dream’ and ‘one nation Labour’, a concept borrowed from one nation Toryism. He even sacked Emily Thornberry from his frontbench for mocking a householder flying the English flag. But nothing seemed to work.

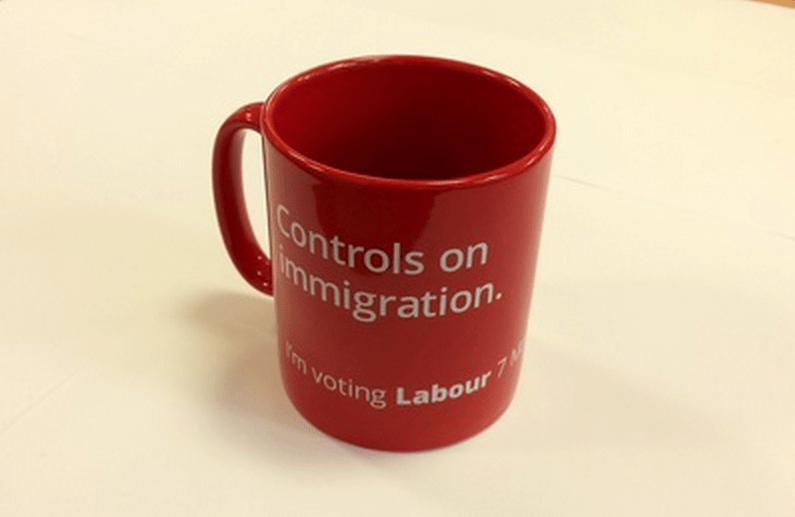

In advance of the 2015 election, and as one last throw of the dice, Miliband launched the party’s five main pledges, one of which was ‘controls on immigration’. While still arguing that Britain had benefitted from immigration, he promised to recruit more border staff, stop serious criminals entering the country while preventing employers from exploiting immigrants by under-cutting wages, amongst many other measures. He hoped to prove that Labour still cared about the issues that those considering voting Ukip felt were important, while not embracing racist anti-immigrant feeling.

As a means of raising money for the campaign, Labour sold mugs on which the five pledges were reproduced, including one that baldly stated: ‘Controls on immigration’. At which point Twitter caught fire with condemnations from Dianne Abbott and Owen Jones, the latter of whom called the ‘Farage wannabe mugs’ to be scrapped. The hashtag #racistmug even trended for a while. For many members, even to talk of controlling immigration — something all nations do — was a betrayal of a principle: in one target seat, the Labour candidate even refused to distribute leaflets which outlined the party’s immigration policy, personally throwing them in a dustbin.

This reaction rather undercut Miliband’s strategy, which was in any case too little and too late to stop his party bleeding votes to Nigel Farage. Yet when Miliband stood down after the disappointing 2015 result, Labour members — with Abbott and Jones prominent among them — turned to the candidate who appeared least likely to pander to anything that might be seen as anti-immigrant sentiment: Jeremy Corbyn.

During Corbyn’s leadership — thanks to Brexit but also to manifesto pledges such as promising to teach the unjust nature of the British Empire as part of the national curriculum — Labour’s relationship with red wall voters deteriorated further. Corbyn did try to appeal to them — he even supported the ending of free movement as part of a Labour Brexit deal. But his anti-imperialism, which saw Corbyn doubt Russia was responsible for the 2018 attack on Salisbury, proved his heart was not in it. Despite Labour advancing economic policies that would have significantly benefitted the red wall, in 2019 it turned towards Boris Johnson.

If Labour’s problems with these voters have got worse since 2015 then many of those who joined the party to support Corbyn mean that its members are even less likely to support the kind of performative patriotism that Starmer is currently employing. For at least the offending immigration mug expressed an actual policy with which they disagreed: Starmer’s embrace of the flag is purely symbolic with no policy implications whatsoever.

Instead of showing that Labour has changed, Starmer has only highlighted how little it has. With the Conservatives intent on fighting a culture war over public statues and monuments, Starmer desperately needs to close down his party’s vulnerability on this truly trivial matter so he can gain a hearing for issues of real material substance such as how best to run the economy, where Labour still badly trails the Conservatives. His members need to decide if they want to argue over the meaning of patriotism or to achieve power. Just now the evidence suggests too many of them still want to play a mug’s game.

Comments