Since I began to watch films on video and not so much in cinemas, I have found that I sometimes get the itch to rewind reality itself, in order to check on what I have seen. There must be many oddities in my way of seeing of which I am less aware. Julian Rothenstein, a one-man art movement, intends to expose some of them in The Redstone Book of the Eye, a collection of almost 300 full-page pictures with very little commentary.

It’s about seeing, and the eye is secondary, really, even though we are drawn to others’ eyes in daily conversation. Or in some cases we avoid eye-contact. In British culture this may signify guilt; in Caribbean culture it may signify deference. It is a pity to mistake the one for the other. Rothenstein includes a photograph by the Barcelona photographer Joan Colom of a man in a crumpled suit, sitting on the kerb and crying aloud (one can almost hear him), while a young man with his girlfriend and an old woman turn to look at him, as they pass by. While Catalans, by and large, are not quite so given to staring as Castilians, the tendency remains, alternating with an acquired ability to blank the socially unwanted.

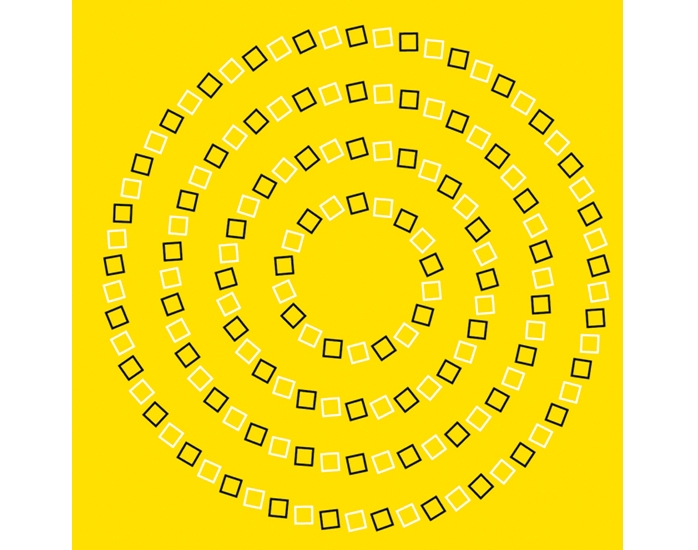

Perhaps the most powerful culture-bound image in the book is of 23 fried eggs arranged on the floor around a lavatory pedestal. It may be clean enough to eat your breakfast from, yet the appetite evaporates. Some of the more mechanical teases in the book are also striking. One captioned ‘Circles or spirals?’, a pattern of angled boxes, simply cannot be credited as a series of concentric circles unless the reader follows the pattern with one finger. This optical illusion appeared in Redstone’s Psychobox (2004), and indeed there is a familiarity derived from past publications about this new Redstone collection that makes it less startling: Soviet illustrations from the 1920s, Mexican folkloric images from The Day of the Dead, inkblot tests, upside-down heads. It might, say, have been good if, instead of yet another ‘three heads, four bodies’ design, it had included an example of the ancient ‘three hares with two ears each and only three in total’ design, mysteriously ubiquitious from Throwleigh in Devon to Dunhuang in western China.

The least reliable section is ‘The Comic Eye’. One man’s laugh is another’s groan, as when we come to Wim Delvoye, a Belgian conceptual artist possibly best known for tattooing pigs. (He has bought a pig farm in China, where attitudes to animal welfare are different from those in Belgium, even though the pigs are anaesthetised when the tattoos are done.) He has also published a series of photographs of trivial messages hewn out of vast rock faces. ‘David, just popped out for a moment, back in 10 mins’ covers an escarpment above a river. Except that the rock-carving has not been made. It is a mere proposal for an art-work, produced from a manipulated photograph. This, I feel makes it less interesting, indeed unfunny. But there it is on page 126. There are times it is best to turn a blind eye.

Comments