Labour had better get used to headlines of economic upgrades. There’s about two dozen major forecasters out there, and each will take a turn to say that Britain’s doing better than they’d thought. To have such good news repeated will be a headache for Labour, as Iain Martin blogs today. But Labour are right to latch on to the caveat: the GDP number are not much use to someone facing a decade of wage stagnation. Words can be deceptive in economics: if you read ten news stories from ten forecasters talking about upgrades, it doesn’t necessarily mean things are getting better. The Treasury recently released five-year forecasts from the people it follows (pdf, here) and it’s not much better than the fairly glum forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Anyway, is Britain growing faster than America – as The Times declared in its headline today? In this three-month period, yes. But the overall picture isn’t as encouraging:-

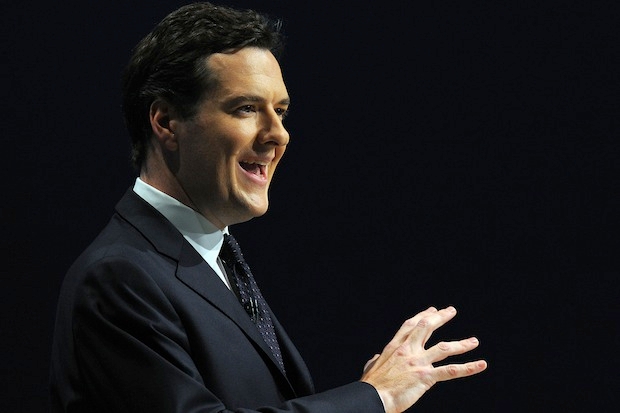

Crucially, immigration is a factor in Britain. It wasn’t so long ago that Osborne’s Treasury was saying that GDP per capita, rather than the headline GDP figures given by the OECD et al, was the more important metric. But this basis, the recovery simply does not exist.

Labour will be trying to focus on wages. And much as though I hate to admit it, they have a point. As Ed West and I argued in a cover piece recently, Osborne’s recovery plan (based on monetary activism but fiscal conservatism) really is a plan for trickle-down economics. The official policy of QE involves reviving the economy by inflating assets. Unsurprisingly, the richest own most of the assets. Those who have investments find the value of these rising. But for those who only have cash in the bank – or no savings at all – there is not much to be optimistic about.

If Labour can get its head around the effects of QE, and work out the the distributional impact of monetary policy is way more scandalous than any tax policy, it may have a critique. Those who have the most assets have done the best, while the poorest face inflation that outstrips earnings. It’s sometimes said that inflation of below 5pc is nothing: remember the 1970s? But what matters the gap between inflation and salary growth. Put the two together, and you get the kind of misery depicted below:-

Comments