‘They’re selling hippie wigs in Woolworths, man… the greatest decade in the history of mankind is over,’ laments Danny the Dealer of the 1960s at the end of Withnail and I. These days, given the apparently insatiable appetite for all things 1990s, you could be forgiven for assuming that they’ve pinched that title. Nineties fashion and music are back: Pulp have just released their first album in 24 years, while Oasis are reforming for a series of mega gigs. There’s even been a Labour landslide.

The Face magazine, which launched the career of the ultimate 1990s supermodel, Kate Moss, is currently pulling in the crowds with its Culture Shift exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, while former Vogue editor Edward Enninful is curating The 90s, which will explore ‘a decade characterised by its bold creativity and rebellious spirit’, for Tate Britain next year.

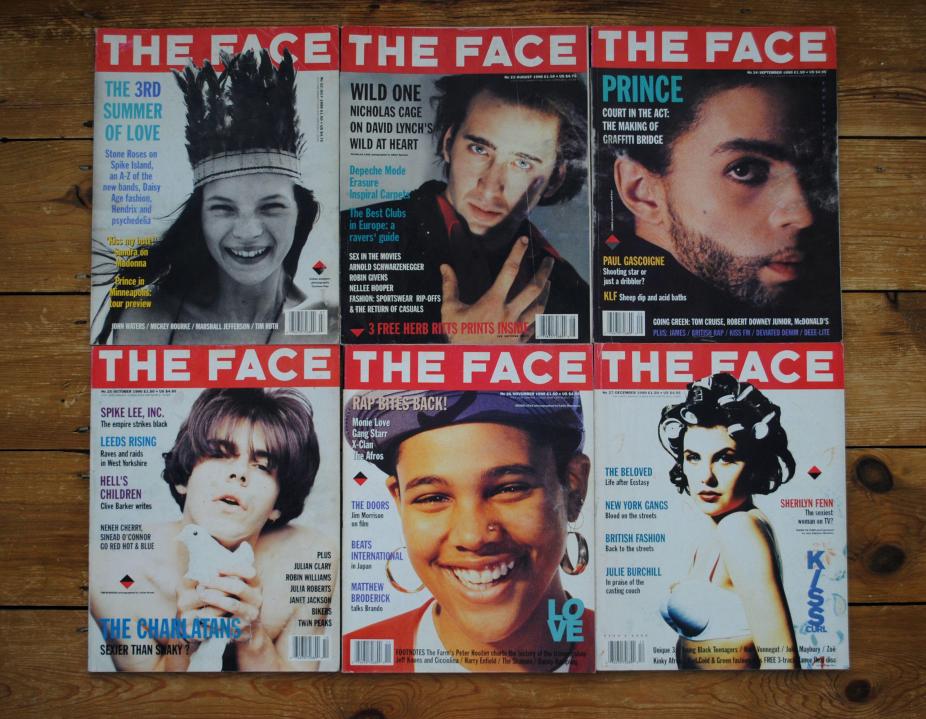

If academics can use the phrase ‘the long 18th century’ to cover a more natural period of British history than that defined by the calendar, then I’m calling it for ‘the short 1990s’. It began with the Face’s ‘3rd Summer of Love’ issue of 1990, featuring a 16-year-old Kate Moss on the cover (pictured above), and died with Kurt Cobain in 1994. That was where the ‘bold creativity and rebellious spirit’ lay – in rave culture, grunge and the anti-fashion photography of Corinne Day. From 1995 it all went a bit Pete Tong, as they used to say.

Every generation tends to romanticise the decade in which they came of age – yet the 1990s were my manor and I don’t get nostalgic about bucket hats, Britpop, cargo pants or the cringe-fest that was Cool Britannia. As a first-time voter in 1997 I remember precisely how long the brave new dawn of New Labour lasted, accompanied by the dire soundtrack of D:Ream’s ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ (one of many nadirs in 90s music).

This, after all, was a decade that started with Italia 90 – ensuring anyone of my vintage starts twitching when the words ‘England’ and ‘penalties’ are mentioned – and ended with the Millennium Dome. Still a child at the start of the 90s, I was too young for acid house, though I could hear the raves on the old second world war airfield three miles away and longed to join them. My cassette of Nevermind was played so much that the tape spooled out and eventually snapped but I never got to see Nirvana live. By the time I was old enough, they’d cancelled all their tour dates after Kurt Cobain’s overdose in Rome. I remember hearing the news of his death on Radio 1 in the village pub where I worked and weeping into the sink of dishes I was supposed to be washing up. Not only was the rite of passage of going to Reading after getting my GCSE results rendered pointless, but now I would never find A Man Who Would Understand Me.

Every generation tends to romanticise the decade in which they came of age – yet the 1990s were my manor and I don’t get nostalgic about bucket hats, Britpop, cargo pants or the cringe-fest that was Cool Britannia

It’s said that a country gets the politicians it deserves, but apparently this applies to bands, too – and I don’t know what my generation did to deserve not only Tony Blair and Gordon Brown but Liam and Noel Gallagher. What my parents had in the hard, bluesy rock of the late 1960s – freedom, sex, rebellion, the things teenagers crave – was absent from smug, self-satisfied Britpop. I wanted Jimi Hendrix at Monterey, not Jarvis Cocker being arch or Blur being ironic. I eventually found the release I desired in the darkest, sketchiest techno clubs when I got to university. Our raving happened inside. With a few exceptions (Portishead, P.J. Harvey, Radiohead) I bought very few albums in the second half of the 90s. The pleasure of going out to a physical store to buy a CD now seems a quaint anachronism.

Much of the 90s nostalgia is driven by Gen Z, longing for a simpler, more carefree era that they never knew. Without smartphones or any form of mobile communication, there was a huge amount of freedom. You could go to clubs and parties that were out of bounds by telling your parents the correct lies about staying over with a friend. Most of us made it out of our teens without needing to be medicated for anxiety. I spent half my gap year in India and only called home a handful of times, though I did write letters.

At the time, of course, we had no idea we were living through the prelapsarian period before the digital age, when social media and the internet would wreck everything from adolescent mental health to enabling Ticketmaster’s price-gouging. We went out a lot and got trolleyed on cans of Red Stripe and cheap ecstasy tablets. There were no ‘sober-curious’ among my friends. Everyone smoked and cigarettes were ridiculously cheap (£2.20 for 20 Marlboro Lights). I was the last intake to get a free university education in 1997.

My mum may have had a blast in the 60s but when she found out she was pregnant at 18, they stopped swinging pretty damn fast. Thanks to the agony aunts in Just Seventeen and More! magazine exhorting us to make him use a condom every time (at the peak of the Aids crisis), 90s teenage pregnancies – in my cohort, at least – were virtually unknown.

The past, as L.P. Hartley said, is a foreign country – but it’s not necessarily one you’d want to revisit. Homophobia, thanks to the long shadow cast by Section 28 and Aids, was rife in the 90s, as one of my oldest friends reminds me. He didn’t come out until after we’d left school. I went to his civil partnership in the late 2000s; they’ve since upgraded to marriage and adopted two little boys. None of this was conceivable in a decade which opened with the ban on openly gay men and women working for the British diplomatic service still in force.

They may be selling bucket hats on Amazon, the Woollies of the 2000s, but you won’t convince me that the 1990s were the greatest decade in the history of mankind – no matter what Gen Z say. All I really miss about those days is Kurt Cobain and having an abundance of natural collagen – that and the cheap fags.

Comments