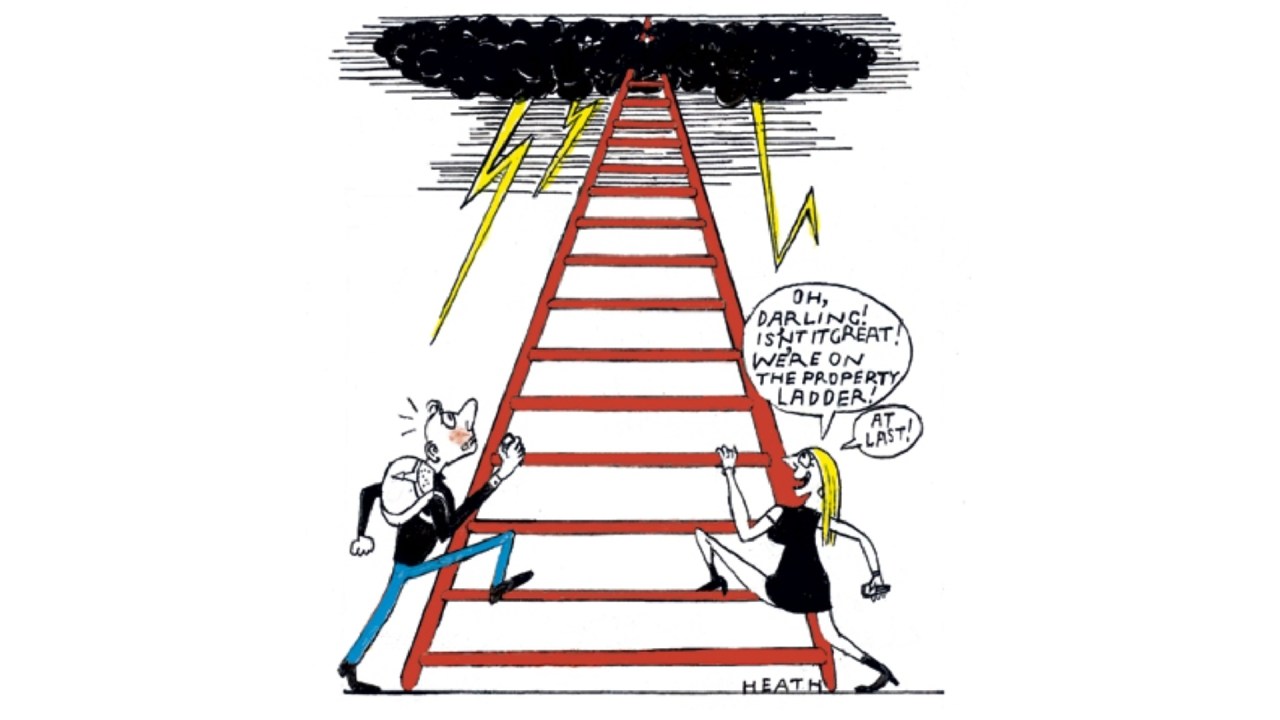

Is there anything that might cause the much-predicted crash in UK house prices? Not – evidently – a pandemic (which perversely caused prices to surge). A sharp, upwards jerk in the Bank of England’s base rate to 4.5 per cent didn’t do it either.

The latest edition of the Office for National Statistics’s UK House Price Index – the most comprehensive of house prices indices, but which tends to trail Halifax and Nationwide – shows that prices rose by an average of 4.1 per cent in the 12 months to March. That is down from 5.8 per cent in February and is lower than inflation, indicating a real-terms fall in house prices. But it hardly represents a crash. And according to Rightmove this week, asking prices are sharply upwards, indicating confidence among vendors that the market will track upwards in the coming months.

Also published this morning, but which tends to be noticed rather less, is the ONS Index of Private Housing Rental Prices. This shows that rents, too, are rising – though not at the rate which some anecdotal evidence would suggest.

Across the UK the average rise in the 12 months to April was 4.8 per cent, with little regional variation on mainland Britain. The rise was lowest in the north east (4.2 per cent). It was 5.0 per cent in London and Yorkshire and the Humber. The highest rise was 5.2 per cent in Scotland and 9.8 per cent in Northern Ireland.

Scotland’s case is interesting because since last October the country has been under a system whereby rent rises are capped for existing tenancies. At present, landlords are restricted to raising rents by no more than 3 per cent once a year. However, there is no restriction on what landlords can charge at the start of a tenancy. The result seems to be that landlords are asking more upfront in order to compensate for their inability to raise rents by more than the statutory amount during a tenancy.

What happens to rents in England from now onwards will be the subject of much intrigue, because of the much-tougher regulatory environment which the government is steadily imposing on landlords. Landlords have already lost many of their tax perks. This alone is reported to have caused many to leave the sector. But now Levelling Up Secretary Michael Gove has revealed proposals to ban so-called ‘section 21 evictions’ which will mean tenants (in most cases) will have the right to remain indefinitely so long as they pay their rent and behave well.

There will be exceptions for homeowners who need to reclaim a property in order to live in it. Moreover, the government is demanding that all rental properties meet at least Energy Performance Certificate grade C (to apply to new tenancies from 2025 and existing tenancies from 2028). This could impose huge costs on some landlords who may be tempted to sell rather than pay for improved insulation. The measure threatens to blight millions of properties. Fewer than half of homes in Britain currently meet grade C on an EPC.

In future, it may not only become illegal to rent those properties; it may become difficult to buy them, too, if mortgage-lenders take fright. It will certainly not help to alleviate a property shortage which has kept property values rising even through a pandemic and the sharpest recession of modern times.

Comments