Most of those commenting on the guilt or innocence of Lucy Letby – the nurse who is serving 15 whole-life jail terms for murdering seven babies and attempting to murder seven others – don’t know what it’s like to work alongside a killer nurse. I do. Benjamin Geen, whom I worked with at Horton General Hospital in Banbury, Oxfordshire, took the lives of at least two patients during his time there.

Something in the nature of our interest in murderers has a habit of making us forget logic

Geen’s case has, like Letby’s, become popular with conspiracy theorists. Public fascination has been far greater with Letby. But the two cases share an attraction for those convinced that they have hit upon the ‘truth’. Living through Geen’s case made me realise, however, that ill-chosen fascinations can give rise to foggy judgements.

When I first met Geen in 2003, he was a cheerful young nurse just starting his career, and I was a junior doctor in the same emergency department. I remember the jokes about how patients stopped breathing on Geen’s shifts; these were gags often led by Geen himself, whose irrepressible cheer could be grating. Some young people are like that, and there is always someone whose shifts seem to coincide with more than the normal number of cardiorespiratory arrests. Given a random distribution of events, there always will be.

The problem was that, in Geen’s case, the events weren’t random. Geen drugged people because he relished the drama and heroism of resuscitation, and some did not survive. Between December 2003 and February 2004, 18 people treated in the hospital’s accident and emergency department suffered respiratory arrests or depressions while Geen was alone with them. Oxford Crown Court, where Geen was subsequently convicted of two murders and multiple counts of grievous bodily harm, heard that he was motivated by a ‘thrill-seeking’ temperament.

How did I miss the signs? Medics often have a habit of engaging in dark humour, but my memories of Geen, more than most, are tinged with it because he was, himself, so good humoured. Even in retrospect, I cannot think of him as alien; I remember him as being much like the rest of us. Had I known him only from reading about the case, I do not think I would view him in this way. I believe I missed the signs for the same reason we all did; except, in retrospect, they weren’t there.

Seeing the attention paid to Lucy Letby, and remembering Geen, makes me feel our interest in these matters inclines us to error. Working with Geen, and, indeed, liking him – he appeared to be a good nurse, and I still think of him as Ben – means that he remains human to me, in a way that those we know through their celebrity do not. But, oddly, that makes me more willing to believe in his guilt. Public commentary has suggested that Geen, like Letby, has been the victim of statistical blunders and legal incompetence, of the sort of complex chain of error beloved of TV dramas or conspiracy theories. Real people, though, are less likely to be caught up in such wild concatenations of misfortune than to simply have hidden flaws. We all do, and some people have flaws that are monstrous.

When the deaths in my department became suspicious, the pattern of events and the duty roster implicated Geen. The police were called in. When Geen arrived at work on 9 February 2004, he had a syringe in his pocket. Seeing the police officers waiting for him, he pushed the plunger down and emptied its contents into the fabric of his fleece. Vecuronium, an anaesthetic agent found in the blood of victims, was later discovered on his clothes. It was a chemical that had no place being in the pocket of a nurse arriving for duty.

Early in my medical career, I entertained the idea of injecting myself with heroin. I had a fever and sore throat. Looking in my medical bag for painkillers, it was all there was. I came close to taking the drug. Later, I wondered if Ben, buoyed by having helped resuscitate someone, failed to resist the urge to misuse the drugs he had access to, and use them to enjoy the same thrill again of bringing a patient back to life. Stepping impulsively across the border of normality can be easier than stepping back; experiences, as well as drugs, can be addictive. One honourable reason for an interest in murderers may be that we become more human when we recognise our own worst traits in the lives of others. Study monsters, and perhaps we are less likely to become monstrous; gazing into the abyss may make us less likely to fall.

We can also be motivated by another honourable concern: the fear that an innocent person is being punished for a crime they didn’t commit. Mistakes do happen; there are many stories of people spending years behind bars when they have done nothing wrong. But in Geen’s case, the idea that he is innocent seems fanciful. In 2009, the Court of Appeal said that the evidence against him was overwhelming; three applications for appeal to the Criminal Case Review Commission have been rejected.

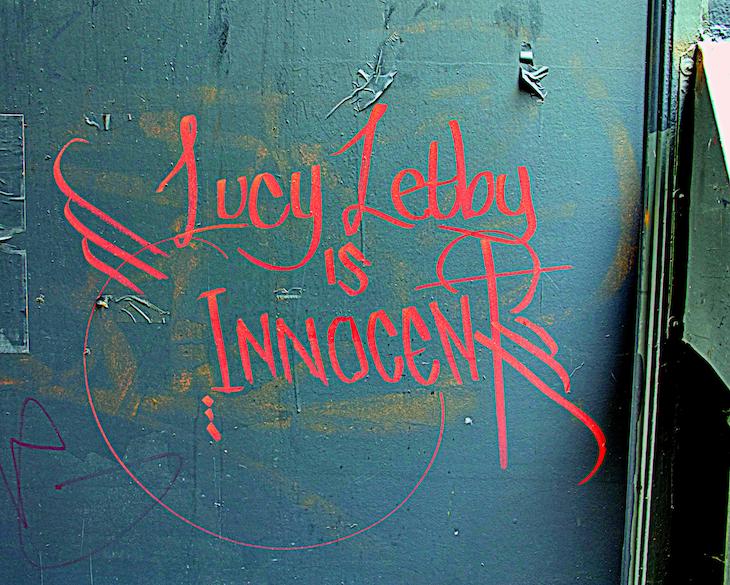

Yet still Geen’s defenders insist, as they do in Letby’s case, that a miscarriage of justice has occurred. What is obvious, though, is that much of the public interest in Letby, as with Geen, is not motivated by the thoughtful doubts or educated questions that arise from serious engagement. By far the bulk of discussion has something of the easy appeal of gossip. Journalists and politicians and those who pass these days for public intellectuals set bad examples when they dive in without fully reading up on a subject; flitting from one trending issue to the next, they parade, with all the glamour of celebrity, a type of thoughtless, opinionated confidence.

It’s odd, of course, to find that a colleague is a killer, and to be swept into the whirlwind that comes when a nurse kills your patients. It is striking, too, that, in the years since Geen was jailed in 2006 for at least 30 years, commentary about his case has ranged from the mistaken and misconceived to the frankly unhinged. The attention his murders garnered is minuscule compared to Letby. Mass murder has a morbid allure that is hideously increased when a pretty young nurse kills babies. But the reality is that morbid fascinations rarely invite our better thoughts.

How did I miss the signs?

Geen was convicted of two killings, but some involved in the case speculate that the true figure could be much higher. We may never know: a few alleged victims of Geen were cremated before suspicions were raised. But there are other commentators, who have no direct connection to the case, who think the real number of Geen’s victims is zero, and that he is the innocent victim of flawed statistics, bad science, and hospital cover-ups. What do they base these assumptions on? As someone who worked alongside Geen and struggled to come to terms with the reality that he was a murderer, I understand that it’s hard to believe that nurses are capable of taking lives, rather than saving them. But I have learnt that the sort of commentary that surrounds such cases is often motivated by hunches, intuition, or misinformed speculation, and less often by the evidence.

Something in the nature of our interest in murderers has a habit of making us forget logic. News, said Evelyn Waugh, is ‘what a chap who doesn’t care much about anything wants to read.’ It is interesting, of course, to pay some attention to the affairs of the day. But it is wise as well to monitor the nature of one’s motives, and sensible to remember that shallow interests yield shallow insights. Forming strong opinions about Lucy Letby seems as profitable as finding reasons to dislike Meghan Markle. Keeping a beady eye on human affairs is part of life, but it is a mistake not to be on guard against one’s own prurience. Geen was guilty of the crimes he committed. I do not believe that the debate about his guilt, or the even more profligate discussion of Letby’s, is driven by objective concerns over the evidence.

Comments