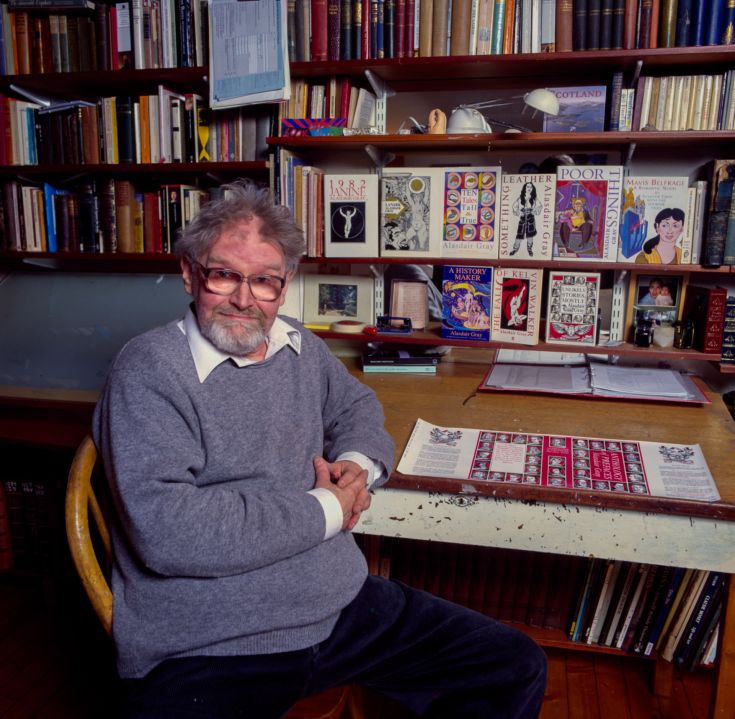

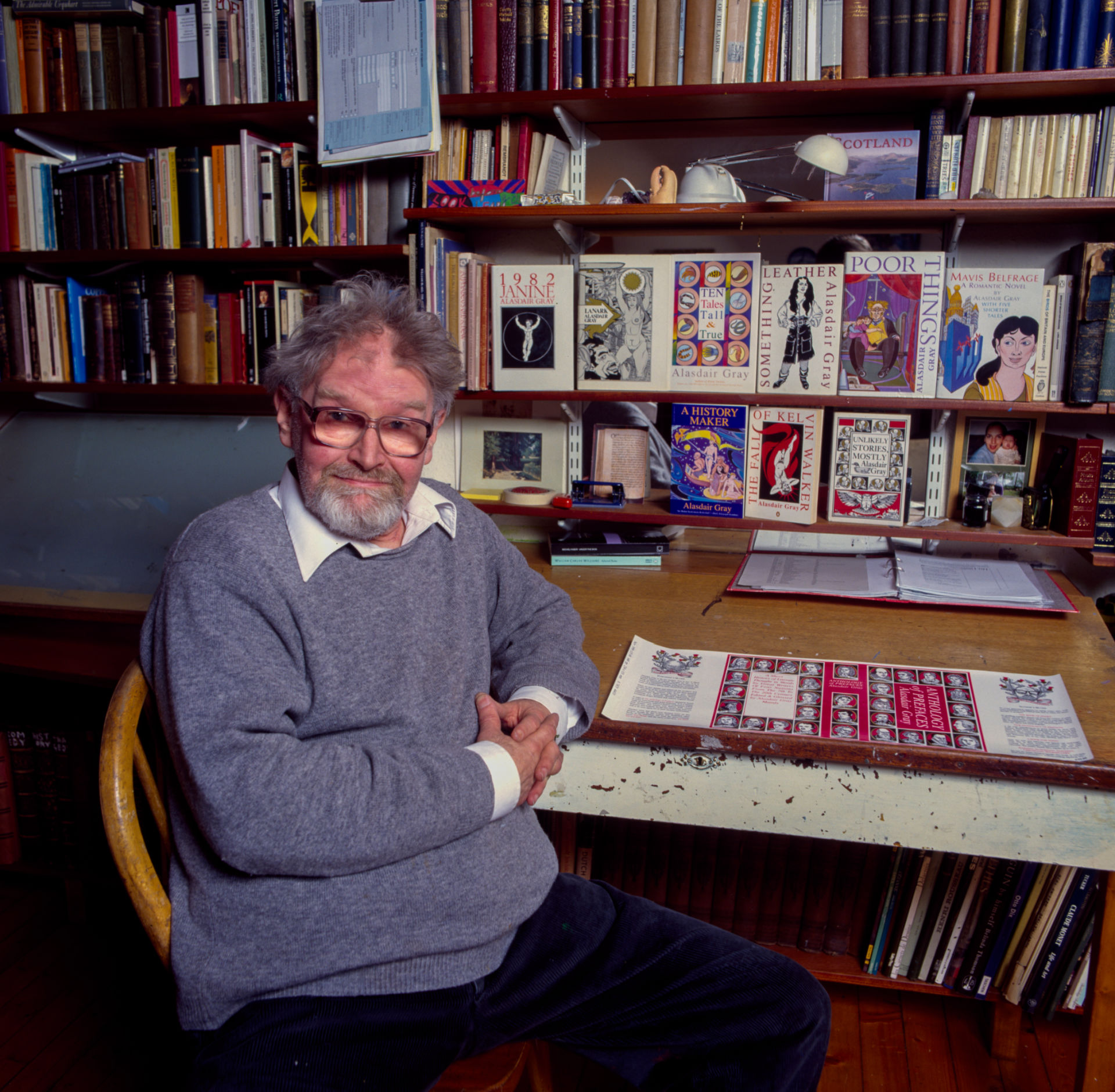

It’s awards season in the movie industry and the film Poor Things, based on the novel by the late Scottish writer and painter Alasdair Gray, is flying high. To date, it has received more than 180 nominations in various award categories, including 11 Oscars and 11 BAFTAs, and has chalked up 51 wins.

What Alasdair would have made of the film version of Poor Things, I don’t know. He could be a hard man to please. It has certainly brought his extraordinary imagination to an entirely new audience. I imagine Alasdair would have disapproved of the film leaving its Scottish roots behind (although Willem Dafoe has an odd stab at a Scottish accent). But the film does full justice to Alasdair’s dazzling vision and I can only think he would have thoroughly approved of Emma Stone’s gleefully fearless portrayal of Bella Baxter.

I met Alasdair Gray when I was a student at Glasgow University, around 1969, when I rang the doorbell of his West End flat to ask him to come and read some of his work for our literary society. He invited me in for tea but was stammering so badly that I began to think a reading was a terrible mistake. Then suddenly, he adopted a performance persona and started quoting the opening lines of Milton’s Paradise Lost (‘Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit of that forbidden tree…’) and he did so fluently and without the slightest hesitation.

Years later, when I was a radio drama producer at Radio Scotland, Alasdair came in to record a tribute to his playwright friend, Joan Ure, shortly after she died. When the recording engineer heard him stammering away, he went white with fear. I said to him: ‘Just wait!’ Sure enough, when the cue light came on, Alasdair read the entirety of his script without the slightest stumble. At the end, when the red light went off, he said anxiously: ‘W-w-was tha- that that all right?’

There are endless Alasdair Gray stories. In the 1980s I encountered him in the Ubiquitous Chip, the fashionable restaurant in the West End of Glasgow. He was painting murals there in exchange for generous payment in meals. (Being Alasdair, he spent the money lavishly, inviting his many friends to join him for suppers.) On this occasion he was painting his distinctive images on the wall behind an ornamental pond and had laid a plank across the pond to enable him to reach the wall. We chatted briefly and I went to join my dining companion. A few minutes later, there was a loud splash and a startled cry. Alasdair had stepped back to admire his work.

When we started work on the BBC film The Story of a Recluse early in 1987, I met him again at the Ubiquitous Chip. The script was based on an unfinished Robert Louis Stevenson story, which Alasdair had completed in a speculative manner. Bill Bryden, then head of drama at BBC Scotland, thought the script wasn’t working and I was asked to take over the production because I knew Alasdair well and it was felt I could negotiate script changes with him. I had been told that Alasdair had point-blank refused to rewrite it and I anticipated a difficult lunch.

However, as we sat down, the first thing he said was ‘If you give me £1,750, I’ll write anything you like.’ It turned out he had put on an exhibition of the paintings of himself and four friends, spent £1,750 on the catalogue and failed to make any money. Now the printer wanted to be paid and Alasdair needed the money. Job done.

I hired the brilliant Scottish director Alastair Reid and we met up with Alasdair at Hawthornden Castle, outside Edinburgh, where he had gone to write. The castle had been purchased by a member of the Heinz family and turned into a writers’ retreat. The warden was a young man busy writing his own first novel – Ian Rankin, working on the first Rebus. The retreat was magnificent, but poised on the edge of a precipitous cliff, with low balustrades on the balconies. When I saw the amount of alcohol that was provided in the evenings, I feared we might lose our author before he completed his mission. Alasdair was certainly a prodigious drinker, but somehow survived.

For the film, he now wrote himself and his producer and director into the decidedly postmodern script. Actor David Hayman played Alastair Reid as a completely manic director, arguing with his writer; Bill Paterson played me as (of course) a measured and sensible producer; we had a negotiation with the actors’ union, Equity, in which we agreed that only Alasdair Gray could play Alasdair Gray. He was literally uncastable. Alasdair duly came to Edinburgh to film with us, including a scene where he narrates the story while the Forth Rail Bridge is noisily being constructed behind him.

The evening after his location filming, Alasdair got very drunk, lost his hotel room key and lay down to sleep in the corridor outside his room. A kindly night porter found him and let him in. Next day, as he came to check out, Alasdair realised he didn’t have enough money to pay his bill, and he had, of course, no credit card. Without telling anyone, he abandoned his luggage in the foyer and left the hotel to find a bank. His disappearance caused a mild panic and I received messages on location that he had gone missing.

Meantime, Alasdair had signed a cheque in the bank and watched the money being counted out on the counter in front of him. The teller asked him for his bank card. He didn’t have it. He was then asked for any proof of identity. He had none. Instead, he left the bank, found a book shop, bought a copy of his book Lean Tales, returned to the bank and showed the teller the self-portrait that adorns that book. They gave him the money.

The Story of A Recluse starred Stewart Granger, a post-war Hollywood heartthrob, in one of his final roles. It also featured Scottish stalwarts Gordon Jackson and Andrew Keir, but these days is probably of most interest for its fledgling star: Peter Capaldi. Peter had graced Bill Forsyth’s film Local Hero a few years earlier but had actually begun his career, like me, at BBC Scotland, where he worked in the graphics department and designed the original T-shirts when I started a radio comedy show in 1981, called Naked Radio.

Rodge Glass, Alasdair’s biographer, tells me that Alasdair was unhappy with the final outcome of Story of a Recluse but does not know why. Certainly, Alasdair never complained to me. The broadcast itself was on BBC2 on Christmas night 1987 and was very successful, despite a bizarre incident. A few minutes into the transmission, there is a fake breakdown in the film, when the action stops and Alasdair himself appears on screen to explain why he wants the story to go in another direction. This ‘breakdown’ was very clearly signposted to the transmission engineers but, obviously, not clearly enough. The duty engineer in Television Centre leapt to his control and stabbed up the BBC test card for a few seconds, until he realised his error and the transmission resumed. He was most apologetic when I rang up to scream at him, so much so that I ended by wishing him ‘Merry Christmas’. In any case, the viewers seemed to think it was a deliberate device, enabling Alasdair to interrupt the action. If Alasdair had thought of it, it might well have been deliberate.

Rodge Glass points out that Alasdair was often an unreliable witness. In his book Of Me and Others, he mentions me as a BBC producer, but actually confuses me with a colleague, Norman McCandlish, whom he felt was letting him down over a different project. This was unfair on Norman, but I’ve always felt it motivated Alasdair when he came to name his main character in Poor Things: McCandless.

I have on my wall a portrait, given to me by Alasdair, of his first wife, Inge. They had a fraught relationship (in fact, at one point Alasdair rented my flat for a few weeks while they were separated) but it is a striking image which I have cherished for forty years. Alasdair Gray was, unquestionably, one of Scotland’s most talented and original artists. With Poor Things his work is finally reaching a genuinely global audience.

Poor Things is in cinemas nationwide.

Comments