Matthew Parris

My father was an engineer. As a child I enjoyed ‘creative’ writing: stories, poems and so on. Dad said: ‘Try writing something useful. You know how to mend a bicycle puncture. Write for me, on one page, instructions for mending a puncture, to be read by someone who knows what a bike is, and what things like “spanner” and “puncture repair outfit” mean, but has never tried to do the job themselves.’ To my own and Dad’s surprise, I really enjoyed this exercise, which demands not just an ability to write clearly, but the mental exercise of putting yourself into a different person’s place, so you can explain. It is really an exercise of the imagination. All of us have experienced the bafflement of reading instructions drafted by someone who is unable to imagine the reader’s situation. In English-language teaching, much emphasis is placed on creativity and style, but the syllabus should specify that the skills of explanation be taught too.

Mary Killen

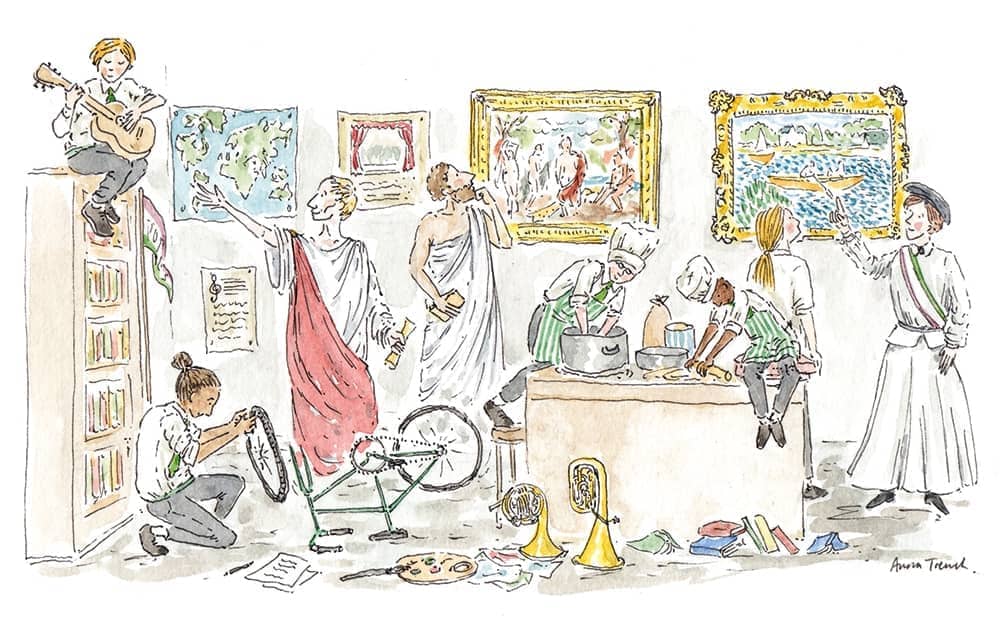

Children would gain so much social, financial and biological advantage from learning how to cook even ten basic dishes. A professional contact in the schoolroom advises that it would be even more productive if they learned in pairs – one child perceived as being ‘cool’ matched with one perceived as ‘uncool’. The exercise would promote bonding between the two tribes.

Peter Hitchens

I would try to see that all children were encouraged to read The Daughter of Time, a crime novel by Josephine Tey, in which a 20th-century Scotland Yard detective examines the belief (popularised by Shakespeare and almost universally held) that Richard III murdered the Princes in the Tower. If even a minority grasped its lesson – that majorities and conventional wisdom are often wrong, and public opinion is often mistaken – the future would be much safer than it now looks.

Jeremy Clarke

I’d bring back Singing Together, the BBC radio programme for schools. Folk songs, sea shanties, calypsos. Our class sang with joyful gusto and togetherness. I still sing them. I’d give older children an understanding of the power of advertising and make them aware they can see more images in 30 seconds than a medieval peasant saw in a lifetime. In every school I would employ a fearsome brute whose sole job is to administer chastisement with a regulation stick. Buddhist monasteries have them. One I saw in Ladakh was about 6ft 5in. He patrolled the child-monks’ lines, dramatically swishing his paddle, alert for the slightest infraction of the rules. The children laughed at and feared him in equal measure.

James Forsyth

What piece of British history would you have every child learn at school? You can make a case for all sorts of things: 1066, the Magna Carta, the Reformation, the Civil War, the Glorious Revolution, the Act of Union, empire or the world wars. But what everyone should reach 18 knowing is how they and their contemporaries came to have the vote. The tale of the expansion of the franchise is the story of the political and social transformation of Britain. At the risk of sounding overly Whiggish, it shows how progress was made and change achieved. It is, ultimately, a unifying story and one that should make us all realise the importance of our vote.

Melissa Kite

When I was a child I had a very wise kindergarten teacher who used to make all her charges sit still and quiet in their little chairs for five minutes of the day. Do they still do that? If not, I would teach ‘doing nothing’ in schools, because people have no patience any more. Teaching children the art of simply being in the moment would transform the world.

Rod Liddle

I was taught using modern educational methods. Something called Colour-Factor replaced mathematics. If it wasn’t for my father, when I was six, forcing me to learn by rote the times tables up to 12 because my school had no time for such reductionist and oppressive methods, I wouldn’t be able to count now. Knowing those numbers empowered me: it gave me an approximate sense of amounts. I didn’t understand the point of chemistry until, two years in, I saw a poster of the periodic table – and learned that by rote too. Once I had learned it and how it fitted together, my interest was at last piqued. Everything of value I have learned has been learned by rote. I didn’t appreciate poetry until I forced myself to recite poems by heart – ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’, ‘Indoor Games Near Newbury’, ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ (this last took some memorising) – then I was in love with it. My school, like pretty much all state schools today, despised rote learning. But it is invaluable, not merely in the acquisition of knowledge, but in the way in which it encourages you to investigate further, to ask questions. Teach them stuff by rote. They’ll hate it – and, later, thank you for it.

Tanya Gold

For children older than 14 I recommend the journalist Martha Gellhorn’s definitive account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the bureaucrat and architect of the Final Solution: ‘Eichmann and the Private Conscience’, published in the Atlantic in 1962. It is a superb piece of reportage: ‘He [Eichmann] comes awake only when documents are submitted in evidence’; ‘The old man cried out suddenly, “A planet without a visa!’”; ‘This man had a mother, a father, a wife, four brothers, four sisters. “I remain alone,” he said, and looked about him as if he did not know where he was’. The Holocaust is an overwhelming subject, but Gellhorn’s conclusions are unstinting, compassionate and practical. ‘We fear him [Eichmann],’ she writes, ‘because we know he is sane… He is a warning to guard our souls; to refuse utterly and forever to give allegiance without question, to obey orders silently, to scream slogans. He is a warning that the private conscience is the last and only protection of the civilized world.’

Rory Sutherland

Mixology. I have a daughter who studied philosophy. This is a pain, as it simply makes her both more argumentative, and better at arguing. This is absolutely not what I want when I get home from work. By contrast, children trained in mixology from primary school onwards would provide a huge solace to tired, fee-paying parents, and the skill would also benefit the pupil and the wider economy, since they could find employment in almost any bar in any country. The dirty secret of higher education is that you actually learn less at any university than you would if you were to spend the equivalent time contributing to the wider economy by working in a decent bar or restaurant.

Taki

As everyone without major brain damage knows, if it weren’t for the Greeks we’d still be living in caves and making hand signals instead of conversing. Hence, were I designing a school curriculum I would require studies of Ancient Greek philosophers, artists, orators, and above all, historians who convey to us the climate of Greek thought. This is harder than it sounds. To understand Julius Caesar it is not necessary to become a Roman general, but to understand Aristotle it is necessary to become, in a small way, a Greek thinker. In today’s world of special interests, full of people preaching their case, Athenian poets and philosophers are experts – as they claimed to be – on goodness and wisdom. Go Greek and you can leave your caves and hand signals behind.

Charles Moore

Every child of secondary-school age must be able to recite by heart a different pre-21st-century poem in English or Latin once a week.

Michael Heath

Music classes daily! Music of all kinds from all over the world to be taught – especially Thelonius Monk – with the exception of Stormzy. Reading. Everything you can literally get your little hands on that has pages as opposed to screens: books, newspapers, magazines and maps. Mobile phones strictly verboten! Excursions to live theatre, opera, the ballet and the cinema. And art galleries. Learn to draw, paint, write, dance and sing. Field trips to foreign places, with the chance to learn new languages and tell jokes in them. Learn social skills as opposed to social media. Be kind to others and they may be kind back to you if you are lucky. Whatever you do, don’t become a cartoonist or a crashing bore.

Lionel Shriver

This is going to sound hopelessly fusty and old-fashioned, but I would re-install the study of grammar and punctuation, which as far as I can tell is no longer taught in schools much at all. When this subject is dropped, children infer, understandably, that the structure of their language is unimportant, and happily adopt the convenient myth that there is no such thing as ‘correct English’. The resultant sloppiness of speech and writing continues into adulthood and explains why even print media and books are now strewn with errors, resulting in a loss of elegance, precision and shared cultural meaning. Start by having all children study Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style.

Bruce Anderson

Leaving aside the utilitarian aspects and science, education should have two primary aims. It ought to inform the young about their country’s history, and about their civilisation. I am only referring to England: the other portions of the UK are different, which brings difficulties. By the time they leave school, English pupils should have a sense of how their country has evolved. Starting at an early age, with Alfred burning the cakes, they should progress to the constitutional and political evolution from the end of the Middle Ages to the modern era. In view of contemporary nonsense, it is worth stressing that slavery had only a marginal impact on English political developments. What do they know of England who only England know? Certainly, but unless the young are grounded in their own country, they will be geopolitically adrift. The young should also know the difference between Rubens and Renoir, while appreciating the glory of western music. Guided by a good schoolmaster (of either sex) they should store up the raw material for a lifetime’s enjoyment.

Martin Vander Weyer

I would insist all sixth-formers learn a useful life-lesson about Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow – which was the basis of my old headmaster’s only joke in his dry-as-dust A-level European History course. ‘Hitler never listened to his teachers. So he failed to heed the lesson of Napoleon’s reversal in 1812 – and was destined to be beaten back from Moscow himself, in 1941-42. But you, idle boy…’ He pointed at me, somnolent at the back. ‘You have now learned this from me: you will never invade Russia in winter!’

Fraser Nelson

I’d force nothing on them. Great mischief has been inflicted upon children’s education by others deciding what they should read – it never works out well. I was given Across the Barricades by Joan Lingard as a pupil: it’s a West Side Story-style tale of a Protestant girl meeting a Catholic boy overcoming the tensions in Belfast. Until that book, no one in my class in the Highlands had any idea that Catholics and Protestants should be enemies, and thought the whole idea hilarious. So it ended up introducing sectarianism where it had never existed before. As the son of an English teacher, I have huge faith in the ability of teachers to know what their class will most enjoy. The wisest words even spoken about education in Westminster were by George Tomlinson, an education minister under Clement Attlee, who declared: ‘The minister knows nowt about curriculum.’ That’s true, with bells on, for journalists.

Comments