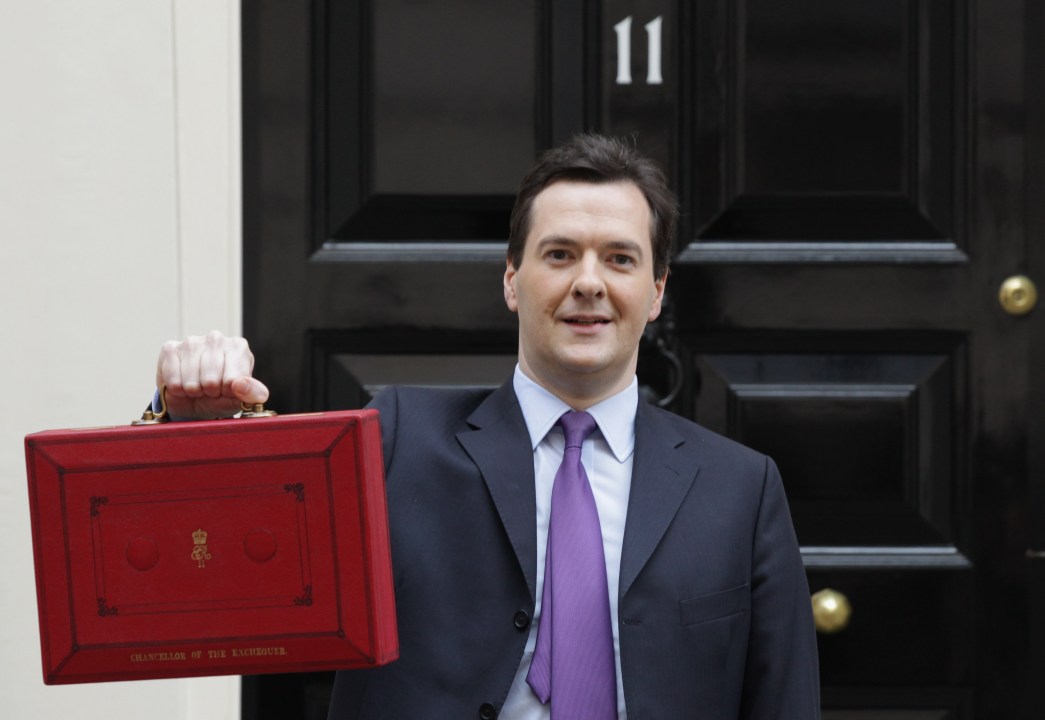

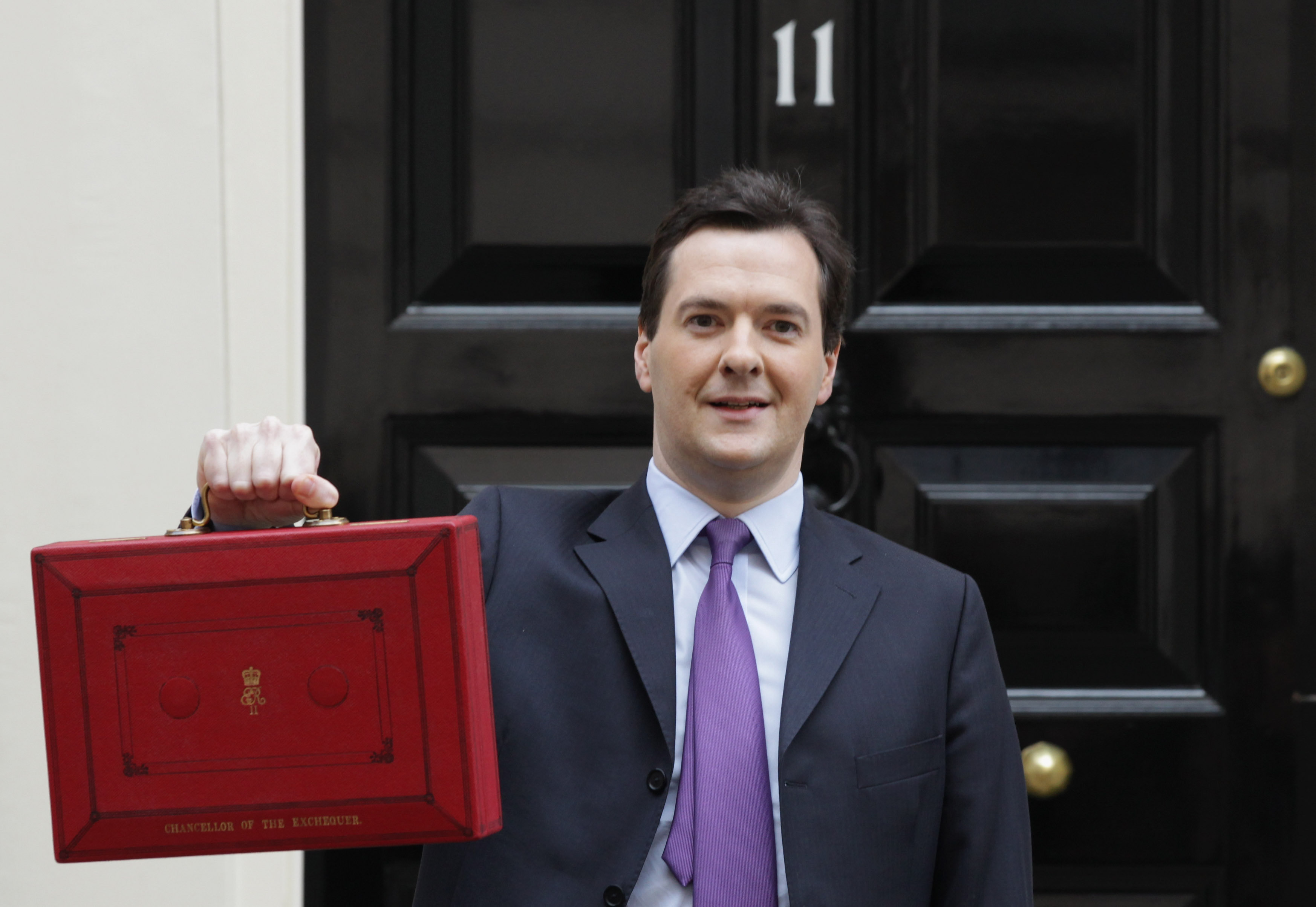

By now, George Osborne will have seen tomorrow’s GDP figures and I suspect will be

having a mid-afternoon whisky. Ed Balls will be warming up for his demands for a Plan B. “Austerity isn’t working,” he’ll say — and will doubtless tour TV studios with his usual

bunch of dodgy assumptions which he hopes broadcasters won’t challenge. Here, as a counterweight, are a few facts and figures about austerity, how harsh it is, etc. — and the case for a Plan

A+.

By now, George Osborne will have seen tomorrow’s GDP figures and I suspect will be

having a mid-afternoon whisky. Ed Balls will be warming up for his demands for a Plan B. “Austerity isn’t working,” he’ll say — and will doubtless tour TV studios with his usual

bunch of dodgy assumptions which he hopes broadcasters won’t challenge. Here, as a counterweight, are a few facts and figures about austerity, how harsh it is, etc. — and the case for a Plan

A+.

1. Where are the “deep, harsh” cuts? The Q2 GDP data will complete the economic picture for the first year of George Osborne’s time in the Treasury. But where are the cuts? The Treasury produces figures for current spending each month. Here they are below, in cash terms and adjusted for CPI inflation. It’s pretty clear that the “fast, deep” cuts Balls talks about do not exist. Osborne does intend to cut, but they are only now beginning to take effect. The GDP data simply cannot be a response to cuts, and it’s economically illiterate to expect otherwise.

2. Osborne’s cuts are only a tiny bit more ambitious that the plans Alistair Darling published in his 2010 Budget. Below we compare the two spending totals, and we look at the rate that debt is accumulating under the two. Under Brown, net debt would have risen by 59 per cent. Osborne plans to increase national debt by a still-eye-watering 51 per cent. The language these two use is very different, but their plans simply don’t differ that much.

3. 3.4 per cent: the secret figure. It suits neither Balls not Osborne to actually quantify the total cuts: 3.4 per cent spread over four years. This basic figure can’t even be found in the Budget document. Why not? Because (I suspect) Osborne wants to make out like he’s a radical deficit-tackler, Balls wants to make Osborne out as a maniacal cutter. The below graph lets the figures speak for themselves:

Strip away the costs of debt and dole, and departmental spending is falling at a faster rate. But this should be seen in the context of the unprecedented rise in departmental spending under Labour:

4. Inflation is the real villain. Mervyn King’s Bank of England has been fighting a losing battle against inflation, at a time when pay has been flat. Result: a fall in real income, and less economic activity. The below graph explains much of the economic pain of late.

5. And inflation, not jobs, is the killer. The IPPR’s “debt is dandy” manifesto today calls for a “Plan B” that puts “jobs first” – a cliché, which has

no grounding in what is actually going on. While inflation has been a killer, employment has not. In those first 12 months, UK jobs have been created at the rate of 1,900 a day giving us the

second-highest job creation rate in the G7. Just who is taking these jobs is, of course, another matter. The Labour Force Survey data suggests that foreign-born workers account for 81 per cent of

the employment growth:

6. Osborne has raised taxes too much. The Chancellor jacked up VAT to 20 per cent in January, contributing to the cost of living problem. He dragged millions into the 42 per cent tax rate. And, in April, the effective top rate of tax went up to 52p (with the NI rise). This is how Britain’s top rate of tax now compares to other countries:

Having the third-highest top rate of tax on the planet is an odd recipe for growth.

7. Internationally, the cuts are hardly drastic. Below are some measurements which put Britain’s modest fiscal contraction into historical and international perspective:

The TUC today said that only a “right wing nutter” would seek to halve a deficit in four years. But compared to other countries, this timeframe is not unduly ambitious. Looking abroad, many countries haven’t even said when they’ll get rid of their deficit, but let’s take the deficit half-life: the time taken to halve the deficit.

8. Osborne’s tough talk has created a problem. The Chancellor adopted Darling’s plan: modest deficit reduction, and rather than frontload the cuts the pain is spread over a long period of

time. But Osborne has created for himself a spin problem. He is talking up his cuts, wrongly comparing the deficit to a credit card balance and talks about “paying down the deficit” as if

such a thing were possible. One pays down debt, not the deficit. All this has created a situation where (according to a recent poll) just 9 per cent realise that the national debt is rising and 70

per cent think it’s falling. Osborne may be taking all the political pain, while making none of the economic progress.

9. The above figures will appear nowhere in tomorrow’s debate. I had hoped that the new Office for Budget Responsibility might make such points, injecting sense into the debate as

the Congressional Budget Office does in America. But the OBR does not intervene, and Osborne dislikes making economic arguments. More’s the pity. In Britain, we seem doomed to debate our economic

future using almost no statistics: I suspect no one, in tomorrow’s reports or Wednesday’s press, will quantify the cuts. The result is that the public is being misled into thinking debt is

falling.

10. We don’t need a Plan B. We need a Plan A+. Osborne has been prescribing plenty of medicine to the Eurozone recently (a cynic might believe he’s planning an “it started in the

Eurozone” as an excuse, if his growth doesn’t materialise), but Britain needs his attention. We are in danger of falling into a high-debt, low-growth trap — the same as has ensnared

Italy. The sluggish GDP growth is due to a combination of domestic and international factors, but has a simple remedy: a plan for growth. I have advocated what I’ve called a Plan A+ which is to cut

taxes for the low-paid. Sweden did this, as a recession remedy, and watched as its unemployed moved into work because they had a far greater incentive to do so. It happened there, it can happen in

the UK.

I’m in Stockholm right now, and this will be my last post for a fortnight: I’m off to enjoy sun, sea and supply-side economics. Things have come to a pretty pass when Sweden has become the best place in Europe so to do.

Comments