‘Have you met Sperm?’ a friend from Westminster School asked me at a teenage party once. Sperm was a charming, pretty, confident girl but, still, I didn’t feel quite ready to use her startling nickname on our first meeting.

My own nickname – Mons, Latin for Mountain or Mount – seemed unadventurously fogeyish by comparison. I didn’t pass it on to Sperm.

Old school nicknames can be fantastically rude – but the ruder they are, the more affectionate

Old school nicknames can be fantastically rude – but the ruder they are, the more affectionate. Sperm happily responded to the nickname – and her friends used it in an utterly friendly way. They had long detached the word’s meaning from its use as a name.

Canvassing my friends, they came up with some extraordinarily insulting names that their schoolfriends still use now they are in middle age: Deafy (a hard-of-hearing boy); Conehead, lovingly abbreviated to Cone; Cyclops, the boy who lost his eye in a javelin accident on sports day; and Sauerkraut, the German girl at an English boarding school. Most chillingly of all – straight out of Evelyn Waugh – was the nickname bestowed in a 1970s minor public school: Mum’s Dead, to which the bereaved boy cheerily responded.

The journeys of school nicknames can be wonderfully complicated. They often derive from opposites. Mastermind, for instance, was the name given to a remarkably dim friend of mine at Eton. Another pal is called ‘Lentil’ – rather a friendly-sounding name until you find out it’s short for his school nickname, Lentil Brain.

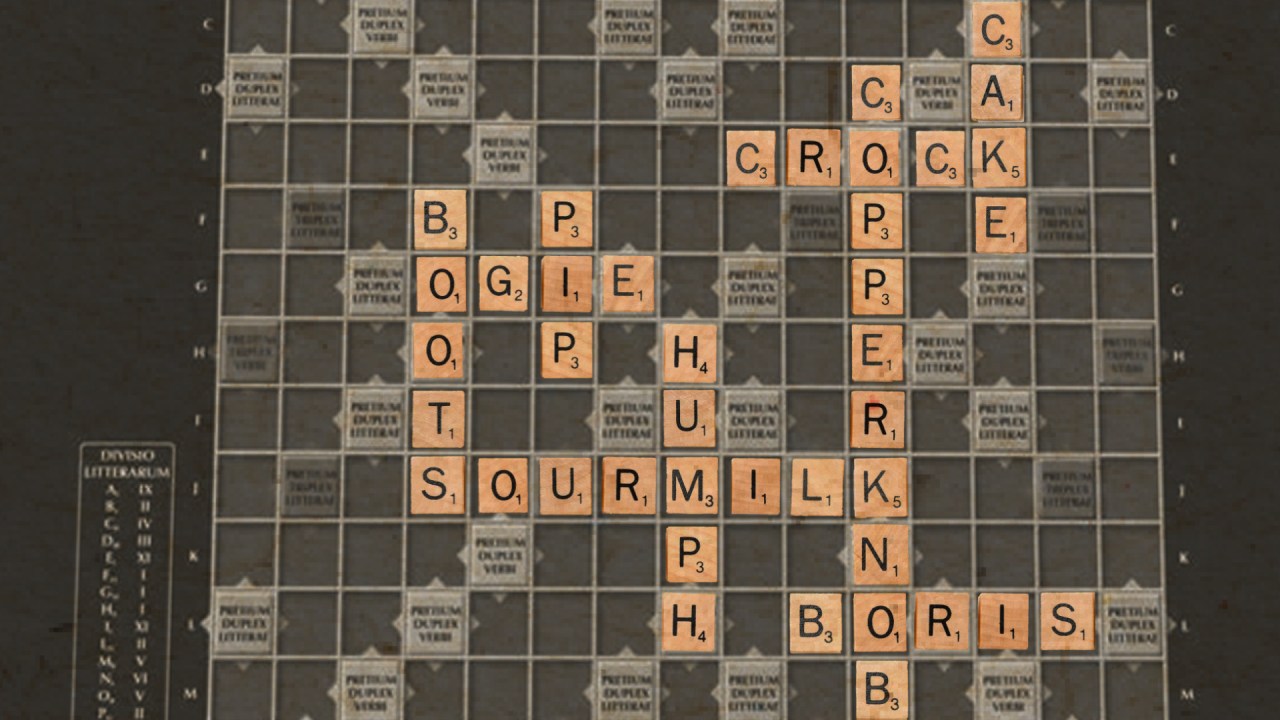

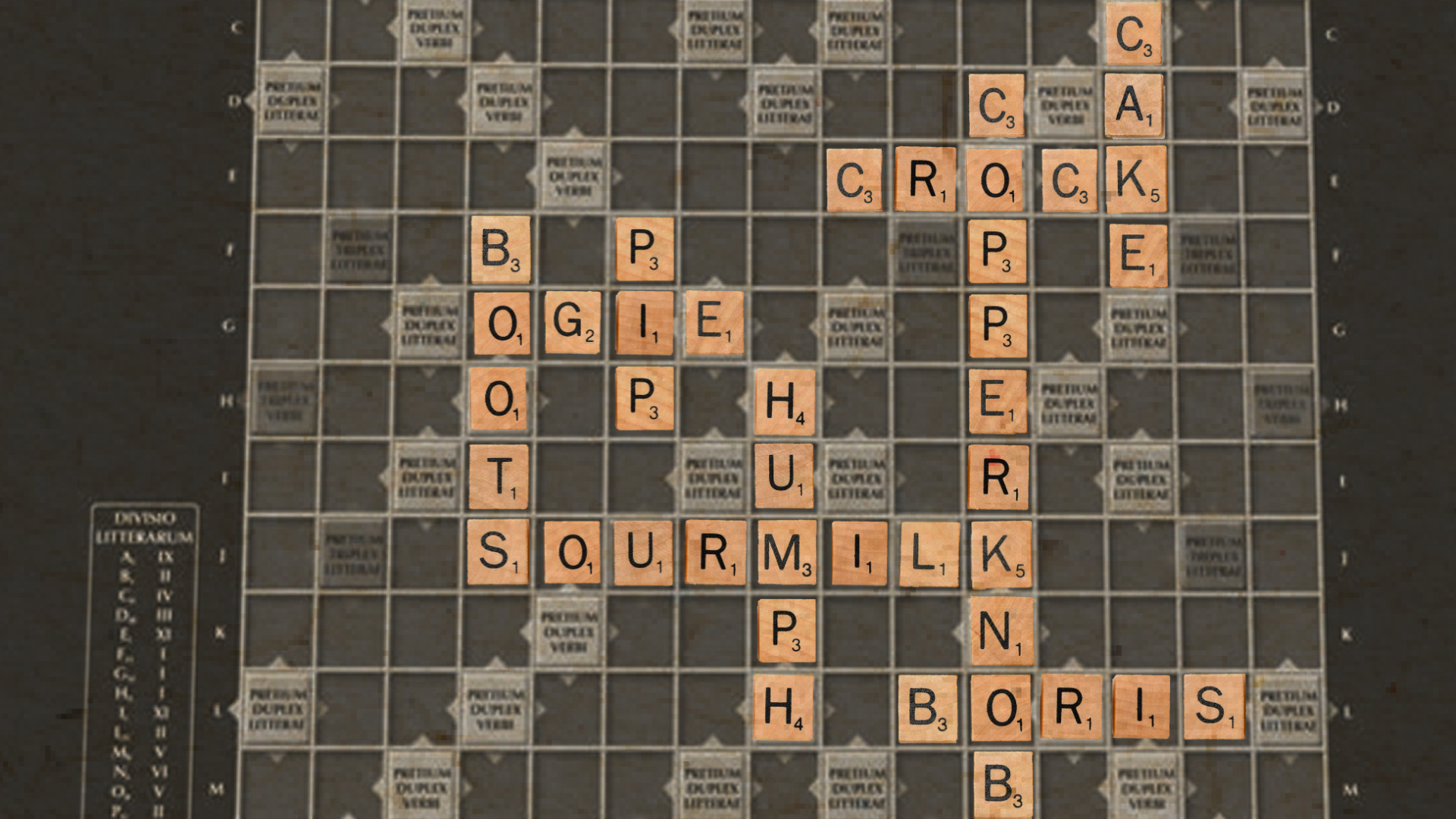

School nicknames have been around for ever. Percy Bysshe Shelley, mercilessly bullied at Eton, behaved in such an odd way that he got called ‘Mad Shelley’. Also at Eton, Aldous Huxley was dubbed ‘Ogie’, short for ‘Ogre’. At Harrow, Churchill was called ‘Copperknob’, because of his red hair. Thanks to his birdwatching prowess at prep school, Michael Heseltine was ‘Great Tit’.

More recently, at Marlborough, Kate Middleton was called ‘Squeak’, and her sister Pippa was ‘Pip’. Perhaps the most famous school nickname of all is Boris Johnson. The only people who use his real first name – Alexander, or Al – are his family. Boris is his second name, which, thanks to its eccentricity, his fellow Etonians immediately latched on to.

Books, too, are great sources of witty school nicknames. Who can forget the Fat Owl of the Remove, dear Billy Bunter?

In Enid Blyton’s classic boarding school novel, The Twins at St Clare’s, Prudence is nicknamed ‘Sour Milk’ by Roberta, known in her own turn as ‘Bobby’. In Malory Towers, Daphne ‘Daffy’ Hope calls Violet ‘Your Highness’ and the teacher Miss Potts is named ‘Potty’ by the girls. In David Copperfield, David is nicknamed ‘Daisy’ by Steerforth, the dandy, because he’s so naive.

Fictional schoolmasters also were given nicknames, notably in Terence Rattigan’s The Browning Version, where the stuffy old classics master Crocker-Harris is known as ‘the Crock’ or the ‘Himmler of the lower Fifth’.

And then there are the old nicknames of the Bash Street Kids in the Beano, Fatty and Spotty, now over-sensitively changed to Freddy and Scotty. How sad that British comics are cancelling nicknames when they used to be the great creators of them: from Minnie the Minx to Roger the Dodger to, best of all, Dennis the Menace.

Even the most horrible nicknames are harmless – when the bearer is happy to use them. But disaster looms when you cook up a nasty nickname for someone that they don’t know about.

A boy at my school, Freddy, had a slight hunchback – thus the cruel nickname ‘Humph’. At least we never used it to his face until the catastrophic day when someone said, ‘Nice to meet you, Humphrey’, having been told his nickname unwittingly and having thought it was his real name.

An American friend tells me nicknames were little-used in his New York schooldays. Their popularity in Britain depends on our peculiar taste for abusing our best friends in order to show intimacy – much easier than having to admit you like them.

That tendency is particularly marked in British private schools and the upper classes. Thus Boots – Evelyn Waugh’s nickname for his old friend Cyril Connolly, short for Smartyboots, thanks to Connolly’s dangerously suspect intellectual pretensions.

The Mitford sisters were inveterate nickname-droppers, as in ‘Cake’, their name for the Queen Mother after she shrieked the word with huge enthusiasm on spotting a large cake at a party.

But the Great British Nickname is at threat in an era of cancellation and sensitivity readers. Nicknames have even been taken away at some universities to reduce ‘micro-aggressions’. Instead, new undergraduates are asked to give the name, nickname and pronouns they would like to be known by.

That defeats the whole point of nicknames – they are conferred by others on you, not created by you. A self-conferred flattering nickname – ‘Charity’, say, or ‘Sweetheart’ – isn’t worthy of the name.

How tragic it would be to lose teasing nicknames. As The Spectator’s agony aunt, Mary Killen, aka Dear Mary, puts it: ‘Nicknames are micro-affections, not micro-aggressions.’

Some of them are too simple and abusive to be touching – I recall dear old ‘Fart’ Moriarty. But many have a bewitching magic, rooted in faraway schooldays, when inspired abuse was turned into a fine art.

Where is Sperm now? We sadly lost touch. But I do hope she has reached great professional heights – Dr Sperm, perhaps, or Professor Sperm CH – where her inspired nickname lives on to amuse new, distinguished audiences.

Comments