Like the fearful townsfolk of Dodge City awaiting the arrival of outlaws, the residents of Notting Hill have been chalking off the hours. Many have resorted to drilling wooden boards over their windows and doors. Some have hired private security and left the city for the weekend. It’s Carnival once again, that annual ritual of comradeship which often degrades into violence, passed off as a community triumph.

Yes, it’s time for the traditional bank holiday fib. If only those most directly affected could speak freely. The police officers, for instance, who must wear coat-hanger smiles, even as they see drugs dealt openly by aggressive young men. These smiling officers sometimes find themselves spat at, punched and headbutted. But they must continue grinning.

They mean well, these coppers, but they’re overrun by hundreds of gang members, for whom the weekend is an unlosable game. To attempt to police the event properly would offend the common law which states that, at Carnival, anything short of murder is considered an acceptable price to pay.

The emergency services might have a few tales to tell when it comes to revealing this bank holiday fib. Last year there were 53 assaults on emergency workers, and 349 arrests for breaches of the peace. One woman was killed by a man brandishing a zombie knife. Another man was beaten to death by a reveller. Eight separate stabbings were recorded. So much for the spirit of fellowship.

Doctors and nurses could also supply convincing evidence. A friend who worked as a surgeon at St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, told me the weekend is the busiest of the year, and by far the most unpleasant. ‘We have to stitch them up,’ he said, ‘not that we ever read about it in the papers.’ Many of the stitched-up prefer not to give names, and are eager to leave hospital as soon as they can, to escape the attentions of rival gang members who follow them there.

This is believed to be the 57th Carnival held in Notting Hill, the parish in west London where many Caribbean folk settled when they came to this country after the second world war. But in recent decades, Notting Hill has become an encampment of new money, where the larger houses can fetch more than £10 million.

What, therefore, is the purpose of continuing to stage this rendering of Caribbean culture in an area dominated by American and French millionaires? Why not move it to Kensington Gardens, as some have suggested? If they can put on pop concerts over a weekend, as they do in Hyde Park, surely there should be no problems with arranging a procession of floats and steel bands. It would also make it far easier for the police to control who gets into the event, frisking visitors as they enter through park gates.

Police officers have been told not to join in the dancing and general cavorting, which seems reasonable enough on aesthetic as well as professional grounds

Why, some might ask, do we need a Caribbean festival at all? Allowing for the fact that traditions can alter over the decades – food being the most obvious example – there is little to unify the different peoples of the Caribbean; not even cricket, a common language of the past, which few now bother to play or watch. Steel bands and calypso, the bedrock of Carnival, come from a Trinidadian tradition, while the majority of West Indians living in London share a Jamaican background.

This confusion is partly why ‘the largest street party in Europe’ has incorporated a subculture of sound systems to bolster the older traditions. Rap is now the lingua franca of the younger generation, though whether this loud and confrontational music would have impressed the Windrush generation must be considered doubtful. But it gives Carnival an edge, so that’s all right.

As usual, the prelude to Carnival has been a kerfuffle. Police officers have been told not to join in the dancing and general cavorting, which seems reasonable enough on aesthetic as well as professional grounds. And some civil libertarians have got worked up about facial-recognition technology, which, they claim, treats black people as potential suspects. Isn’t everyone a potential suspect? Just as I’m a potential rapper, given I have a larynx and too much time on my hands.

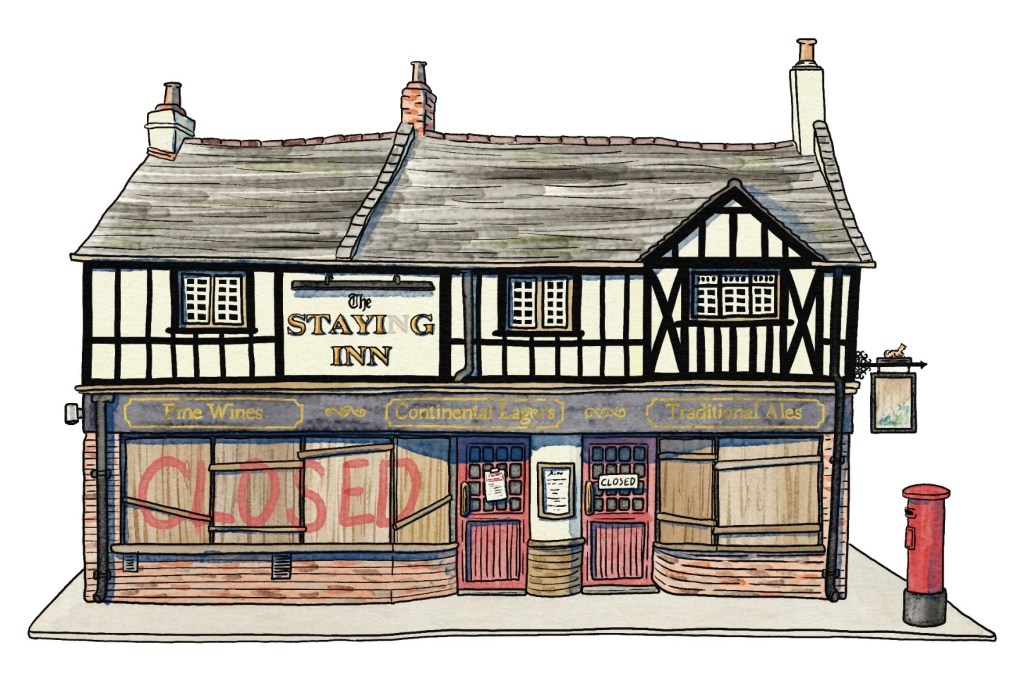

Is it worth it, this festival which disturbs a whole corner of London and regularly leads to death? Once upon a time, when violence was less of a feature, the answer was an emphatic yes. Then it became a guarded yes. Now there appears to be no good reason at all.

Life will of course resume once the sound systems are wheeled off and the locals return to clear away broken glass and mop up the blood. A police spokesman will blush as he says Carnival was a joyous occasion, enjoyed by thousands of well-behaved revellers. The organisers will claim it was the best yet. Until next year.

Comments