This book falls into two parts. The first is a brisk account of Britain’s involvement with India and of the backgrounds of those people who were principally responsible for unscrambling that relationship. It contains most of the facts that matter, if rather too much social trivia that does not, and is generally fair. Where it is unfair is in its dismissal of Mountbatten as a trivial playboy. It is permissible to make fun of some of the wilder schemes which he championed during his time at Combined Operations — notably the iceberg-aircraft carrier Habbakuk — but unreasonable to dismiss the ingenuity, energy and formidable organising powers which created the machine that made possible the invasion of Europe in 1944. Mountbatten was, indeed, often preoccupied with trifles, or with his status as a member of the royal family, but to claim that he ‘engaged himself almost full time’ in arranging the marriage between his nephew Philip and the future Queen is absurdly to underestimate the range of his activities and to exaggerate his role as matchmaker.

By the time that the second part of this book begins — dealing with the coming of independence and the partition of India — the reader (or, at any rate this reader) is therefore expecting a hatchet job on the last Viceroy, a reprise of the gospel according to Saint Andrew Roberts. The contrary proves to be true. Harold Nicolson in his diary remarked how curious it was that ‘we should regard as a hero the man who liquidates the empire which other heroes such as Clive, Warren Hastings and Napier won for us’. But, von Tunzelmann goes on:

Mountbatten was serving his country with as much loyalty, courage and determination as had those other heroes. Mountbatten turned a stagnating mess into perhaps the most successful retreat from empire in history — from the point of view of the imperialist nation, at least.

She examines the three main charges against him — that he mishandled the problem of the Sikhs, failed to make proper use of the British army, and transferred power with disastrously reckless speed — and acquits him on all of them. Certainly she criticises certain aspects of his operations but she is equally ready to show that all the main protagonists — Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah in particular — were at times guilty of obstinacy, pride, ill-temper and rank bad judgment. She conveys vividly the terrifying pressures under which they were all working: the massacres that besmirched partition were bad enough, but von Tunzelmann leaves one in no doubt as to how much worse they might have been.

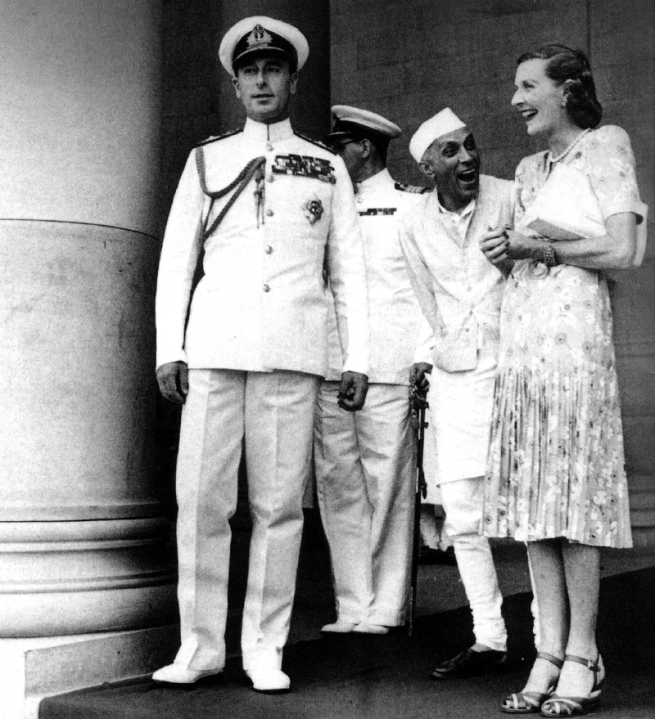

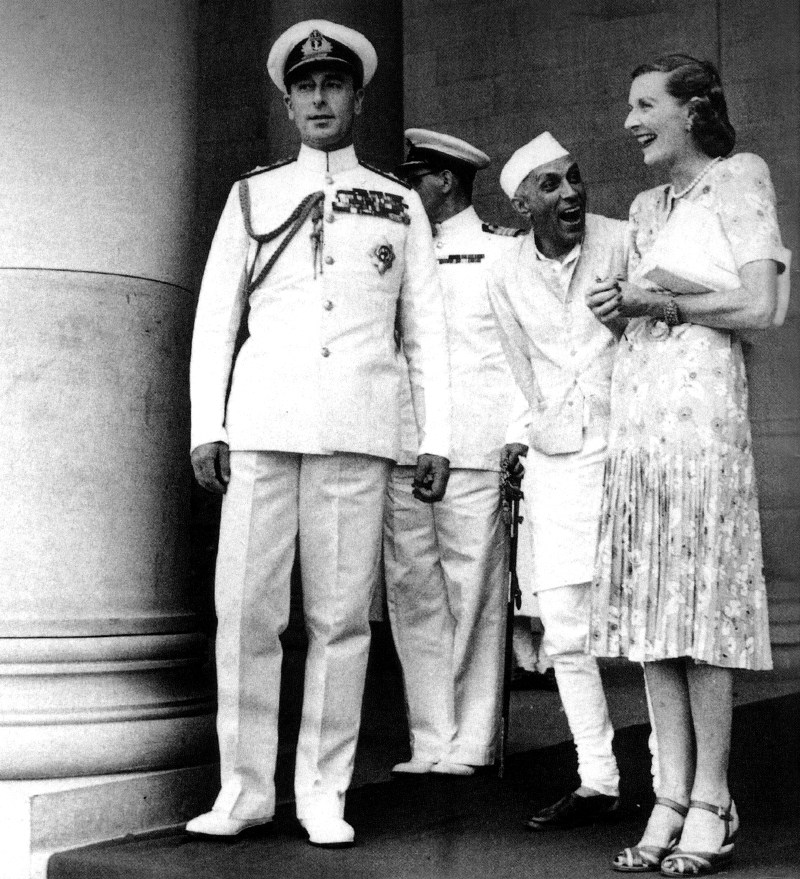

The heroes are all shown to have had their frailties; the heroine, Edwina Mountbatten, is alone almost immaculate. Her achievements were, indeed, prodigious, but the author exaggerates her importance — sometimes it seems as if Mountbatten would have been incapable of performing his task without her constant guidance, if not control. The remarkable relationship between Nehru and the two Mountbattens is described with sympathetic understanding.

Von Tunzelmann suggests that the ‘affair’ between Nehru and Edwina began far earlier than May 1948 — ‘the line later perfected by official biographers’. It depends what you mean by ‘affair’. No one doubts that a close friendship existed while Mountbatten was still Viceroy but Nehru himself dates to a weekend in Simla in mid-May the discovery that ‘there was a deeper attachment between us, that some uncontrollable force, of which I was only dimly aware, drew us to one another’.The point is of importance, since Pakistani historians in particular insist that Mountbatten as Viceroy was prejudiced in favour of the Indians because of Nehru’s baleful influence, exercised through the Viceroy’s wife.

The subtitle of this book, ‘The Secret History . . .’ suggests that the author has had access to hitherto unknown sources and is offering the reader sensational revelations. If such sources exist they are singularly well concealed. Von Tunzelmann has, however, worked conscientiously through a mass of published and unpublished material. From it she has created a compelling narrative, sometimes controversial, occasionally perverse, never boring or unintelligent. It will be interesting to see what she tackles next; there is every reason to hope that it will be well worth reading.

Comments