In recent years, sensitive music critics have attempted to replace krautrock with kosmiche as the consensus term for the wild and wonderful music that exploded out of West Germany during the 1970s: Can, Neu!, Cluster, Faust. A word that literally translates as herb-rock, cooked up by glib Brits who had read too many war comics, lacks a certain gravitas, and nobody would describe Tangerine Dream or Kraftwerk as rock anyway. The Hamburg journalist Christoph Dallach opens his invigorating oral history with a spirited argument about the label, but sticks with it anyway. So krautrock it remains.

In this story, it is impossible not to mention the war because no country in the world has been less at ease with its recent past than Germany. ‘We wanted to understand and compensate for it with our music,’ says the free-jazz saxophonist Peter Brötzmann. Teenage rebellion against parents meant something very different when those parents had served on U-boats or the Eastern Front. Those too young to remember the rallies and air raids themselves grew up around teachers and neighbours who used to be Nazis but didn’t like to talk about it.

Thus, saturated in trauma, shame and denial, the krautrock generation talked about the necessity for a cultural zero hour long before punk did. With barely any German heritage to build on, a resistance to emulating Anglo-American rock’n’roll and no conventional commercial ambitions, they designed their own futures. As Can’s titanic drummer Jaki Liebezeit puts it, they were ‘making something out of the cultural poverty of a total breakdown of civilisation’. There really was nothing to lose.

Dallach sweeps us from the shell-shocked aftermath of the war to the crazed ferment of 1968, when musicians crossed paths with communards and future terrorists. Life in Berlin’s Kommune 1 sounds like an exhausting cycle of orgies and meetings, and even the orgies had rules. You get the impression the musicians were constantly eluding conversations about the class struggle. In some bars, recalls Faust’s Hans-Joachim Irmler: ‘If you went in on a Monday, you could think yourself lucky if you got out again on a Wednesday.’ The krautrockers may have resembled the radicals – a whole chapter is devoted to the significance of long hair – but their revolution was purely musical. According to Jürgen Dollase of Wallenstein: ‘The 68ers were uptight – we 69ers were hedonists.’

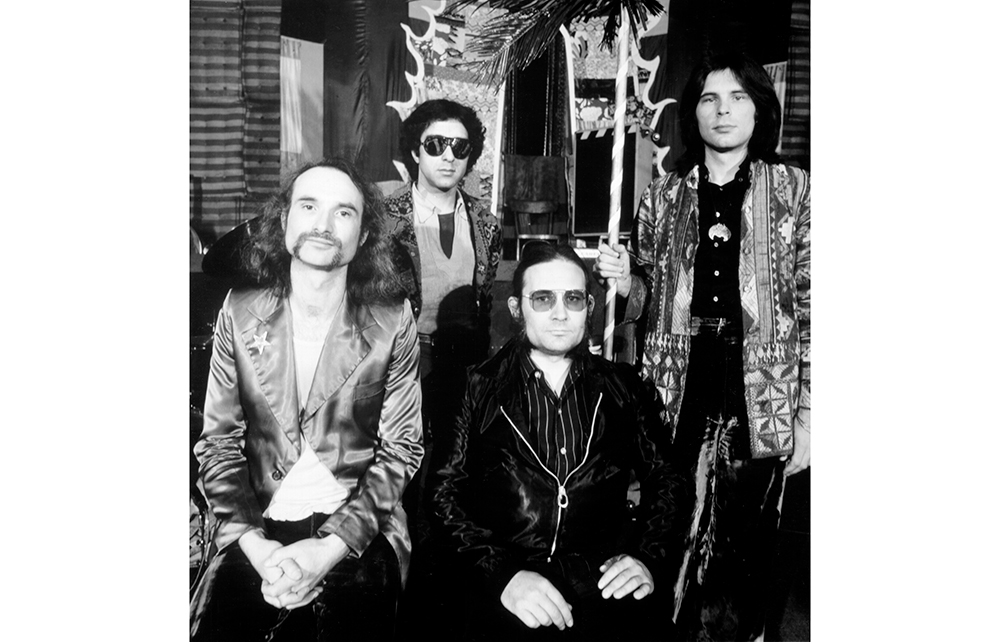

The dearth of life-changing hits, agonising fame and tales from the road sets Neu Klang apart from most scene-based oral histories. Its cameos include not only David Bowie and Iggy Pop but Werner Herzog, Bridget Riley and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Krautrock describes a time, place and attitude rather than a sound. There were amiable collaborators and frosty hermits, sleek futurists and shamanic noisemakers, classically trained virtuosos and impish disrupters who could barely play. What united them was a tremendous sense of freedom. Synthesiser pioneer Klaus Schulze sums up the general ethos as a ‘third way’ between pop and the avant-garde.

One poor soul claimed to have discovered ‘the sound of all sounds’ and was determined to tell the Pope about it

The music may invite earnest reverence, but the stories behind it are often hilarious. Neu!’s gentlemanly guitarist Michael Rother recalls being incapacitated by a hash cookie midway through a show. Fortunately, ‘no one at the gig cared; the whole audience was completely stoned anyway’. Faust isolated themselves in a remote squat, walked around naked and were once raided by police with machine guns on suspicion of belonging to the Red Army Faction. Their record label optimistically billed them as ‘the German Beatles’. Another standout character is Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser, the psychedelic Svengali who liked to spike his bands’ drinks with LSD and record the lengthy results. One poor soul claimed to have discovered ‘the sound of all sounds’, a surefire hit, and was determined to inform the Pope about it.

The members of Can appear throughout the story as droll refuseniks: no to dogma, no to hippies, definitely no to communes. ‘Our political act was Can,’ insists the fabulously highbrow Irmin Schmidt. They were an anti-rock band in which five giant egos somehow managed to commit themselves to equality. They would improvise for days, then edit the best bits into an album and never played the same show twice. At the end of one unusually challenging night of screams and drones, the last man standing was, of all people, the actor David Niven. ‘It was great,’ he said, ‘but I didn’t know it was music.’

This is not, despite the subtitle, a definitive story. In a scrupulous oral history, major figures who have died or have declined to talk are voiceless. But Dallach caught many of them in time and asked the right questions. The great irony of krautrock is that Germany’s most enduringly influential gift to popular music was beloved abroad but snubbed at home, as if nothing valuable could emerge from Germany. There is something heroic about the musicians’ determination, in the face of apathy and hostility, to turn a cultural landscape of ghosts and ruins into a garden of delights.

Comments