Bit late now, isn’t it, to complain about the exams debacle? Where were they, Angela Rayner, Keir Starmer, the teaching unions, Nicola Sturgeon and the BBC on 18 March when Gavin Williamson fatally decided to scrap this year’s A-levels and GCSEs? If they were throwing their rattles out of the pram, it wasn’t loud enough to be heard.

The grounds for that idiot move was ‘to give, pupils, parents and teachers certainty, and enable schools and colleges to focus on supporting vulnerable children and the children of critical workers’. That, you note, was before the start of lockdown. Yet if ever there was a problem that could be seen a mile off, it was the consequences of this disastrous decision. It is an unlovely trait to say I told you so… but I told you so, here. Cancelling exams was guaranteed to cause problems out of all proportion to the supposed benefits. As we now find.

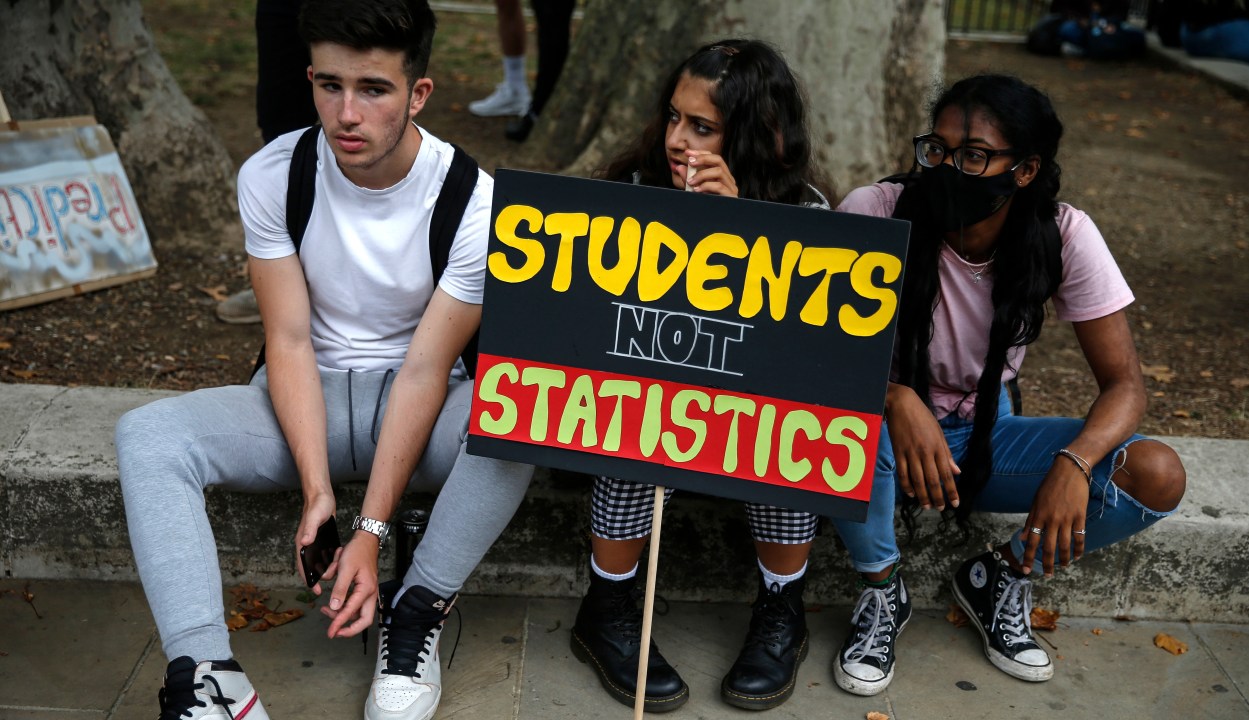

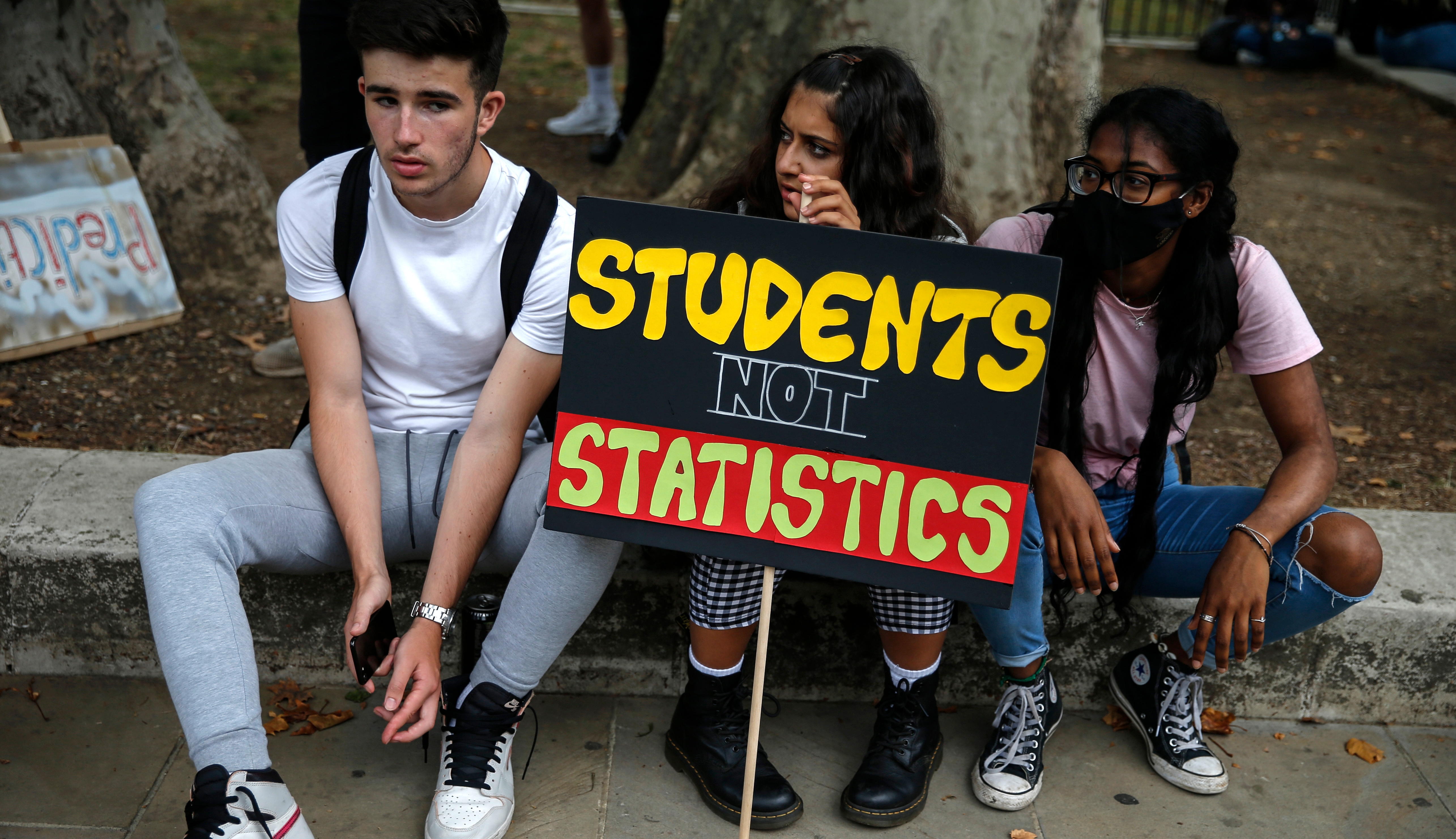

The fuss is happening now, but any idiot could have seen this coming

Examinations could have been held if there had been the political will to do so. But it would have required the Education Secretary to have reversed his decision by mid-April at the latest to give schools and exam boards time to prepare. It would probably have required the exams to have been postponed a little, until July, to allow for unique circumstances, with results a little later than normal. It would, crucially, have required teachers actually to teach pupils from two year groups for three months as opposed to not teaching them at all.

My son will be getting his GCSE results on Thursday – until there’s a U-turn on that too; give it time – and he has had just two, possibly three actual lessons since the start of lockdown. In physics. And his school is rated outstanding. So, he’ll be returning in a couple of weeks without any actual tuition for six months. That is, if he is returning. In his school, you need to perform well at GCSEs to be admitted for A-levels.

If there had been exams, schools would have had to prepare their pupils for them. They’d have had to reopen for those year groups – and since they were open anyway to teach key workers’ children, clearly that wasn’t out of the question – or have had to organise proper structured online classes, just like private schools were doing. As The Spectator pointed out in this week’s editorial, private schools managed to teach a far greater proportion of pupils than state schools. But to say as much doesn’t quite do justice to the real situation. Private school pupils had an actual school day throughout lockdown, with proper classes in different subjects. State school teachers simply put assignments online and left pupils to get on with it. Some teachers marked the work that was sent in, and chased up work that wasn’t. Most didn’t bother.

That would not have been acceptable if heads’ minds had been concentrated by the prospects of exams. They’d have had to provide poorer students with laptops to allow for online classes; more to the point, teachers would have had to teach. Some schools could have physically opened – used canteens, sports halls, open spaces, and staggered classes. They would have had to cancel study leave after Easter when students are normally left to get on with their revision at home – which I’d quite like to see done away with anyway. And schools would certainly have had to open for the exams themselves and invigilate them. All that would have been difficult, but it was definitely doable. And yet it wasn’t even attempted.

In the absence of exams, how did Ofqual think it was going to arrive at a formula for estimating grades that wasn’t either inflated or unfair? Requiring teachers to rank pupils in grade groups isn’t a guarantee of integrity. Poor schools and department heads, given an opportunity to inflate their own performance, were unlikely to pass over that opportunity. As we find in Scotland. Yet relying on mock exams was inherently unfair given how many pupils went into them with a light heart, not thinking that – surprise! – these would be one of the means used to judge their hypothetical performance. The rules of the game were changed retrospectively, after 70 minutes of play. How did Ofqual think that was going to work out? The fuss is happening now, but any idiot could have seen this coming.

But the problem goes further back than March. When the PM appointed Gavin Williamson I thought it was a bit weird. I mean, you could see Mr W as Business Secretary, just about, if you were charitable… but education? Was Boris mad or did he just not give a toss about the most important department in government? The latter, it turns out. There hasn’t been a good reformist Education Secretary since Michael Gove, but to give the job to somebody with absolutely no discernible aptitude for it was bound to end badly, and that was before the pandemic struck.

It’s too late now to put any of this right. And it’s the PM who’s squarely to blame.

Comments