For more than twenty years, Brian was left to rot on a methadone prescription. Month-after-month of opioid replacement therapy was the best course of action, his treatment team concluded, making no effort to definitively end his debilitating drug dependency. For Brian’s parents, watching their son slowly succumb to the steely grip of addiction, it was two decades of agony. Then, in 2018, a ‘top up’ hit of street Valium proved too much, and – as they put it – he was at last ‘released from his torture’.

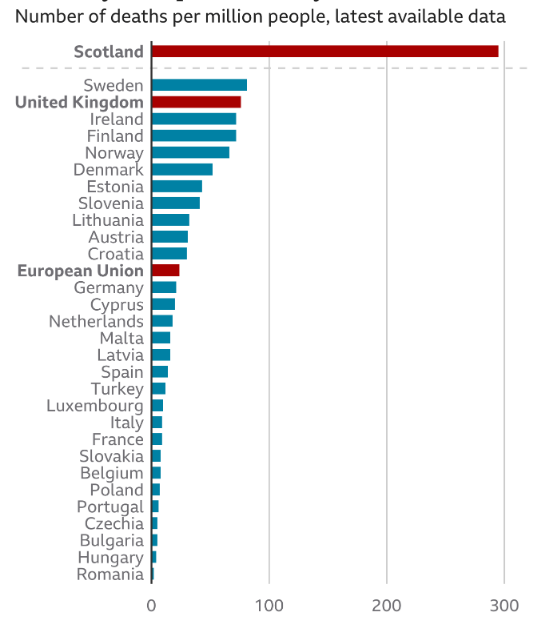

In Scotland – which has the worst recorded drug death rate in Europe – such stories are disturbingly common. But is the SNP doing enough to tackle an epidemic which is spiralling out of control?

Last year, more than 1,200 Scots lost their lives in drug-related cases, figures released today reveal. It is the nation’s highest drug death rate since records began, more than three times that of England and Wales.

Worryingly, the worst is almost certainly still to come. When, next year, the human cost of 2020’s coronavirus turmoil is counted, a further jump is anticipated, with Police Scotland reporting ‘significant increases’ in drug-related deaths during lockdown.

Behind each of these individual tragedies – young men and women robbed of their futures, heartbroken families hollowed out by years of vicarious suffering – there lies a bitter political struggle of blame between the SNP and Westminster.

Scotland’s SNP government has long called for a radical drugs policy rethink, pushing for safe consumption rooms and the effective decriminalisation of Class A substances for personal use. Pro-independence ministers argue that this would safeguard the most vulnerable addicts, stem the spread of blood-borne viruses, and slash the number of overdoses.

But the UK government – which oversees Scottish drug law from London – isn’t convinced. A report by the Scottish Affairs Committee echoing Edinburgh’s calls was roundly rejected by Whitehall recently, with ministers pointedly refusing to declare a drugs-linked public health emergency north of the border.

But Scotland’s festering drugs crisis isn’t merely a result of Westminster intransigence. For over a decade, SNP promises of progress have fallen flat. Yes, policy innovation is hampered by the strictures of half-century old UK legislation, but that doesn’t explain – nor excuse – the parlous state of Scotland’s fragmented and under-resourced addiction services.

It is no coincidence that cuts to treatment budgets since 2015 (stretching into the tens-of-millions, according to some estimates) have coincided with accelerating drug deaths. And although back in February Edinburgh pledged an additional £20m to help reverse the trend, it seems that lessons simply aren’t being learned.

‘That money isn’t new, it’s a restoration of funding that was cut over the last few years. We need genuinely new money, as well as a dedicated drugs policy government minister or Recovery Champions like they have in England’, Annemarie Ward, chief executive of Faces & Voices of Recovery, told me recently.

On the frontline of the nation’s drugs emergency, her group – which helped Brian’s parents – takes particular issue with the government’s commitment to a methadone-focused treatment system. ‘It just isn’t what gets people well. You’re just holding them, you’re managing their symptoms, but you’re not actually helping them get well,’ argues Ward.

The static nature of Scotland’s opioid replacement model isn’t the scheme’s only issue. Methadone – an exceptionally potent substance – was implicated in, or potentially contributed to, almost half of 2018’s death toll, official statistics reveal. Misapplication is a massive issue, too, with around half of patients estimated to be on too low a dose, compelling many – like Brian – to ‘top up’ with a dangerous cocktail of street drugs

Is there a better way of dealing with Scotland’s drug problem? It is obvious that a balance needs to be struck between harm reduction initiatives (like the methadone programme) and services that strive to get people off drugs altogether.

In Scotland, what is clear is that not enough money is allocated to rehabilitation schemes, with many patients funnelled towards opioid replacement schemes. This failure by the Scottish government to focus on getting addicts clean is why talk of safe consumption rooms feels hollow. Removing dirty needles from circulation and paring back the incidence of overdose are, of course, laudable ambitions. But without efforts to wind down the habitual drug use of those in greatest need, the cycle of death and despair in Scotland will never be broken.

Alasdair Lane is a Scottish journalist

Comments