Almost the whole of the British political class failed to understand that the rise of Ukip after the 2010 general election was not some fringe irrelevance but was in fact likely to have major consequences.

Academics Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin were two of a select band of political futurologists who were onto the Ukip advance early. By the time their insightful book Revolt on the Right was published, Ukip had already forced an EU referendum pledge out of David Cameron and the book was therefore read by many dumbfounded Westminster insiders as if it were a crammer for a module that had unaccountably not been covered in the standard curriculum.

Ukip’s arc rose and then fell away just as rapidly, and its brand is surely now too tarnished to allow it to be the vehicle for any new ‘Revolt on the Right’.

But the absence to date of any such sequel is both a curiosity and an important part of the contours of our politics. On the left, Keir Starmer and Labour face a plethora of alternative parties dug into serviceable niches and with parliamentary representation: the Lib Dems, the Greens, the SNP and Plaid Cymru.

Where Ukip looks like a has-been, various other entities risk becoming never-weres

All these parties occupy space on the liberal-left and all therefore limit Starmer’s ability to tack hard back towards the blue collar and socially conservative ‘Red Wall’ voters Labour has lost. All, for instance, are for more foreign aid, more immigration and more indulgence of progressive ID politics.

Yet no party of the right on the British mainland has any representation in the Commons other than the Conservatives. Where Ukip looks like a has-been, various other entities risk becoming never-weres.

Chief among these is Reform UK, the successor outfit to the pop-up Brexit party that lived and breathed for one tumultuous year. Under its new leader Richard Tice, Reform is flatlining in national opinion polls at around 2 per cent, seems unlikely to secure representation on the Greater London Assembly or in devolved chambers in Scotland or Wales, and is heading for humiliation in the parliamentary by-election in Hartlepool, where Tice won a 26 per cent vote share in Brexit party colours in 2019.

Then there is the Reclaim party of Laurence Fox and pretty much only Laurence Fox. The voluble actor has achieved a big social media following and has wealthy backers but was brought back down to earth with a thud last week when a poll came out showing him running at 1 per cent in the race to be London Mayor. There are then several other right-wing start-ups that would love to have even that single percentage point under their belts, such as the Heritage party set up by ex-‘Kipper David Kurten.

It is not as if these parties have no issues to go at. Lack of delivery on immigration control, the continued suspension of core civil liberties, high taxes and public spending, excessive foreign aid, the massively expensive zero carbon drive and the sacrifice of free speech on the proverbial ‘altar of political correctness’ would all seem to amount to low-hanging fruit for a right-wing insurgency.

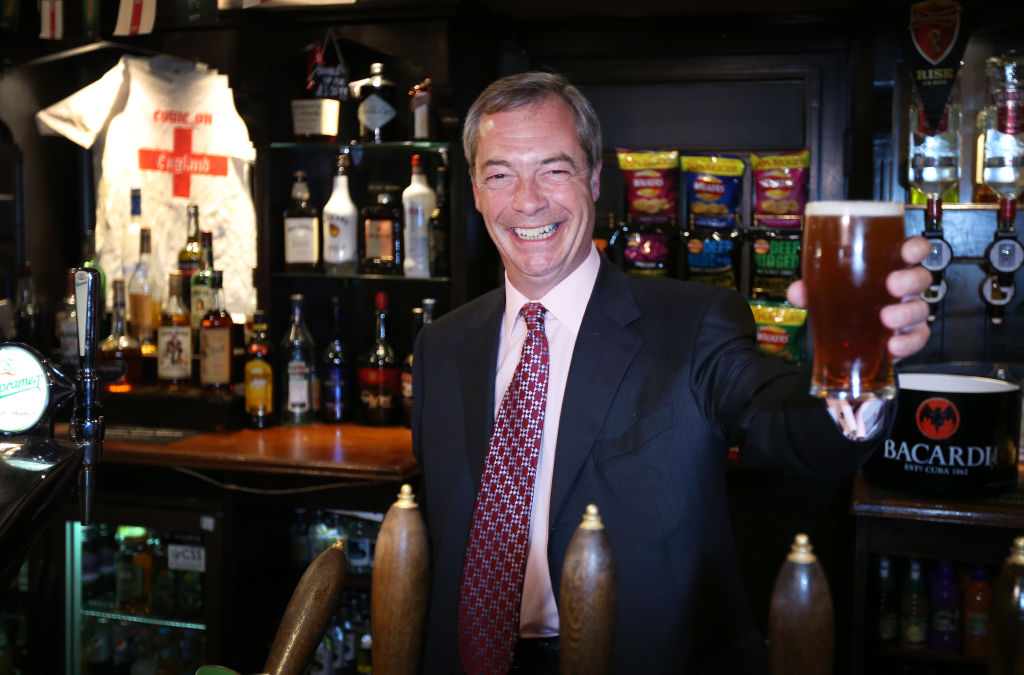

So why isn’t it happening? For starters, getting a political party going is a time-consuming undertaking. Local branches of active members must be formed to establish footholds in actual communities and render the entity real rather than merely a series of tweets. The Brexit party was a singular exception to this rule thanks to the extraordinary prevailing circumstances and the fame and association of Nigel Farage.

The withdrawal of the Farage factor from the scene is another problem. There is no single natural talisman for the right outside the Tory party. Irked right-wing voters do not know where to turn to register their disgust.

Just as importantly, there isn’t actually all that much disgust around. The PM’s strong second half showing in the battle against Covid – especially on the vaccination front – is keeping the vast majority of the electoral coalition he assembled in 2019 on board. That is bolstered by bullish economic forecasts and the success of his administration in holding unemployment in check in the face of the pandemic.

Equally, the would-be challengers seem to be prioritising the wrong issues. There may have been 20,000 or even 100,000 people marching against lockdowns in London on Saturday, but polling shows the vast majority of voters are comfortable with the pace of unlocking. That is hardly likely to change as unlocking advances.

Tice’s Reform UK – by far the most credible candidate for lift-off – seems shy of getting engaged in emotive ‘culture war’ issues or even prioritising immigration control, preferring instead to bang the drum for smaller state, lower taxes Thatcherism. Tice was said to strongly believe such an approach would gain traction in Hartlepool as well as Hertsmere. Well, it hasn’t. Not in either place.

Should Tice manage to get himself onto the GLA next week at least he will have secured himself a stable perch and some democratic legitimacy. If he doesn’t then it is hard to see Reform UK amounting to much.

It may just be that when voters gave Boris Johnson that 2019 landslide they were also giving him the right to do things his way for a good few years and most people will not be in the mood to reassess anytime soon, no matter what scandals are presented to them by a breathless media.

Any young academics looking to make their names with a new tome about right-wing insurgencies would be well-advised for now just to keep tabs on the best navigator of these currents. When Nigel Farage returns to the fray – as he probably will one day, whatever he says now – it will be a sign that the wind is back in the sails. For now, a flotilla of vessels under the command of rookie sailors is struggling even to get out of harbour.

Comments