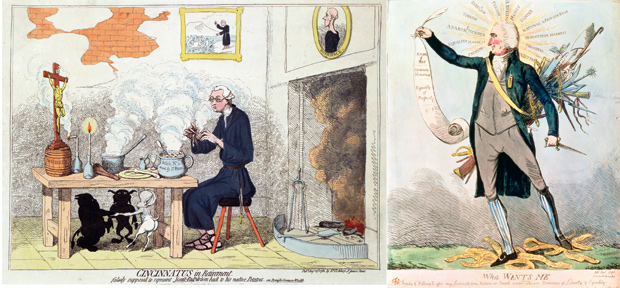

What is the origin of left and right in politics? The traditional answer is that these ideas derive from the French National Assembly after 1789, in which supporters of the King sat on one side and those of the revolution on the other. Yuval Levin in The Great Debate, however, argues not for seating but for ideas: that left and right enter the Anglo-American political bloodstream via the climactic public clash in the 1790s between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine, the prime movers in a pamphlet war that convulsed opinion and engaged readers on two continents.

If this is right, then the touchstone of modern political debate in Britain and America is not capitalism v. socialism, or religious fundamentalism v. cosmopolitan secularism, but an earlier and deeper disagreement over the nature of the modern liberal political order itself.

In late 1790 Burke published his Reflections on the Revolution in France. That revolution had been celebrated from the first amongst intellectuals, radicals and bien-pensants in Britain, and many people naturally assumed that Burke the great reformer would join his protégé, the Whig leader Charles James Fox, in acclaiming it. It came as a profound shock for them to read the Reflections — both a profound statement of political philosophy and a devastating critique of revolution itself.

To none was the shock greater than to Thomas Paine, who had made his name as the author of the revolutionary tract Common Sense in 1776. Now he saw that Burke’s book demanded a rapid and equally trenchant public response. The result was The Rights of Man. There followed dozens of further pamphlets, as opinion divided over the issue, while the revolution in France descended — as Burke had predicted — into anarchy, terror and war.

Levin, editor of National Affairs magazine, described as a ‘one-man Republican brains trust’, sets the scene well. On the one hand we have Burke, the ‘philosopher in action’. Here is a man who combines deep learning and reflection with a mastery of the facts at hand, is always conscious of the limitations of individual human reason and sees society as a priceless providential inheritance, which each generation must maintain and enhance for posterity. On the other hand there is Paine, whose hatred of authority in any form is so great that it extends even to acknowledging previous thinkers (‘I scarcely ever quote; the reason is, I always think’). He is a man who rejects the claims of tradition and convention and seeks to reconstitute government and society itself according to abstract reason.

Levin is commendably even-handed—perhaps too much so. Burke was often overblown and self-righteous, but without doubt he was a man of enormous personal integrity and dignity. Paine, by contrast, rarely retained the admiration of his supporters. He was a shameless sponger, who was sprung from jail in France by James Monroe (the future president) only to stay on in Monroe’s house unbidden for two years afterwards. Having tried to ingratiate himself with Burke, he later ran a wholly dishonest campaign to denounce him (falsely) as the recipient of a ‘masked’ or secret royal pension.

But the differences go deeper than this. Burke is a genuinely complex thinker. He operates at many levels, across a wide range of fronts; he has a very subtle understanding of how facts condition theorising; and it takes real time and effort to engage with him. Paine is not complex at all; indeed he rejects complexity as such. For him what matters is the unimpeded exercise of abstract individual reason in the moment. His simplicity is a crucial source of his rhetorical power. Yet its effect is to reject deep truths in favour of straightforward falsehoods, and to lead him into contradiction.

So, then, are these two truly the first framers of left and right? At one level, clearly yes: as I have argued myself, Burke is the first conservative and Paine is a canonical radical. But what is so striking is the degree of cross-dressing in politics today, as slogans overtake reflection amid an endless search for genuine legitimacy and authenticity. Indeed the irony is that, as government has grown, so has the number of self-professed Burkeans of the left seeking to preserve the status quo, while Paineans of the right want to begin all over again.

Needless to say, this misreads both Burke and Paine; indeed it makes one despair for the future of Burkeans, especially in American politics. This excellent book will tell you why.

Comments