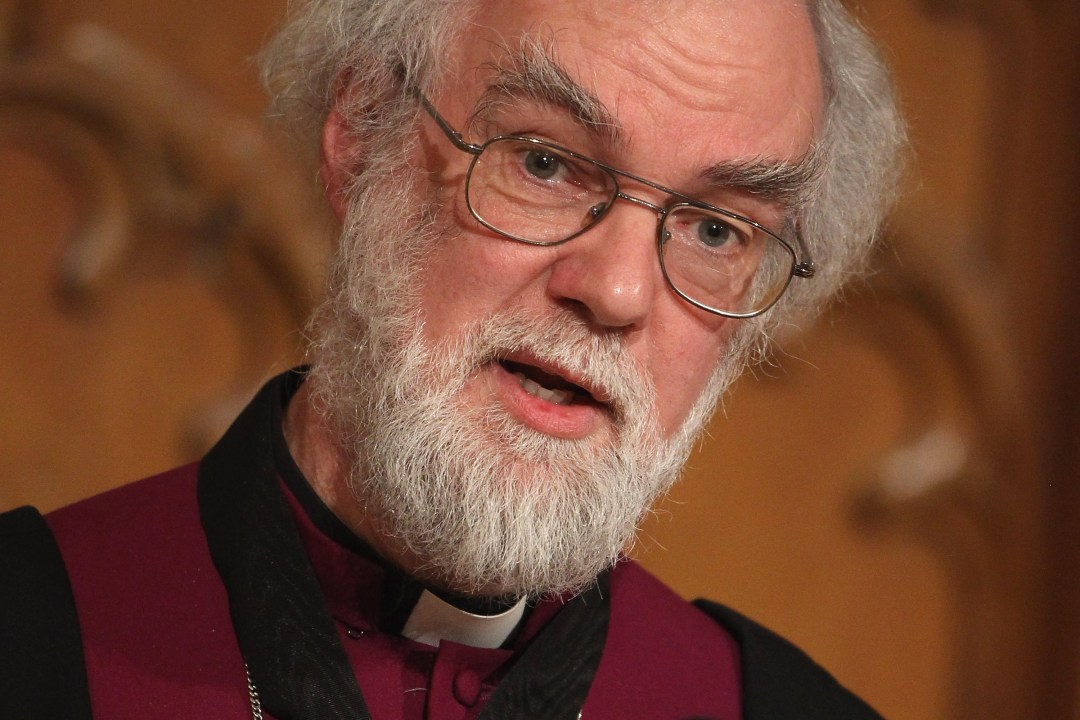

Rowan Williams will step down at the end of 2012, having been Primate of All England for a decade. It is already clear that his term of office has been disastrous. Church people have affection for him, respect even. He is not blamed for the disaster, since he is only doing a job he was asked to do — not one he sought. He was a bishop of the Church in Wales almost by accident, because of his academic fame, not because he had ever wanted to be a career bishop.

Nobody has accused him of ambition, though there is perhaps a little vanity there — about his poetry and his interest in the remoter depths of philosophy and theology. But he seems a lot more genuine than, for example, the disappointingly flaky Bishop of London, Richard Chartres, or the invariably grandstanding Archbishop of York, John Sentamu — and he possesses a spiritual sincerity, which draws on his unpretentious, compelling concern for the disadvantaged. Being Archbishop of Canterbury has been for him a burdensome, unrewarding task. The beard and untidy hair have made him extremely recognisable. Rowan’s image promises (more than anything he has actually said) a touch of John the Baptist. Unfortunately, it has been impossible for those outside or on the edge of the Church to be clear what he believed in or wanted.

He has probably failed to hold the Anglican Communion together. Yet its angry splits seem less significant than he feared they might be. Handing on Anglicanism in one piece was to his mind what justified his stance on homosexuality: that someone in a physically active and publicly known gay partnership should not or certainly could not be consecrated to the episcopate. It has not occurred to him that ordinary people, including church members, do not regard bishops as a special category on some hotline to the Almighty from which Deans, for example, are barred. And that therefore his readiness to have homosexuals becoming deans as consolation prizes simply looks hypocritical, irrational and absurd to most people — who do not want to have their own Archbishop apparently kowtowing to evil prejudices apparently endorsed by senior Anglican clerics in parts of Africa.

But his biggest failing has been his poorly communicated vision of what he senses really matters about the Church of England as an English institution. It does not of course mean the same to the whole English nation, but it is a rock in our culture — regardless of whether one is a non-conformist or an atheist. There was never before an Archbishop of Canterbury who seemed not to believe in that in his bones and in his heart. But Rowan is a Welshman and an intellectual, and believes in the Church of England as merely a part of a much larger historical accident. No other Archbishop would so readily have accepted the downgrading constitutionally implied by Gordon Brown’s decision as prime minister to abdicate the choice between two candidates for CofE bishoprics — including Rowan’s successor, whoever he or she may be. If it no longer matters to the nation who the CofE chooses on its own account to play this role (what is implied by the deal between the Scottish PM and the Welsh Archbishop), why maintain the charade of establishment, except as some sort of ongoing respect for the small, genuinely convinced element in the population — including immigrant minorities who may be more consciously serious about how religion supports their culture than many non-paying or non-playing ‘members’ of the CofE.

It is nearly seven years since he explained to me why he had to remove himself from any particular line. He talked about ‘trying to secure a fair debate’ rather than being achiever of a manifesto, and he sees this ‘above the fray’ role as being appropriate for all bishops — though as No 1 Archbishop he also said ‘I can’t speak as though my views were the views of the Church’, being (as he is) conscious of the ‘megaphone effect’ of the office. ‘When I try and say something in the public arena about issues of public concern, I have to try and identify matters than can be pretty firmly anchored in common Christian conviction.’

The trouble is that this is not how most archbishops have behaved. Even the saintly Michael Ramsay allowed himself to be strongly identified with Anglican-Methodist reunion and exposed his sadness

when that suffered defeat. The two decades since Rowan’s own Anglo-Catholic ‘party’ in the church split apart in 1992 — when Liberal catholics broke ranks to give the women

priests measure its narrow two-thirds majority — have been specially ill-suited to a hands-off approach from an Archbishop who in effect has knuckled under as the new

‘Evangelical’ majority has secured its power in the CofE. Rowan’s attempt to ‘Speak for the Church’ in a way that, as he puts it, “can claim to be more than just

an individual’s ideas’ has not really fitted the bill. For the last decade, it has felt as if a carnivorous institution were being led by a vegetarian.

Anglicanism is a reformation tradition, reflective of adversarial English politics, where over the centuries people have agreed to disagree. Rowan hasn’t played that game. Instead he has

given the impression of not speaking from his own heart, but more like a doctor who tells you what’s good for you or (even worse) what he feels the good book implies. In truth it does not

matter much exactly what people in the CofE pews think or believe. Like the clergy they believe a very wide range of different theological propositions. But, very specifically, people do not want

to be told what they ought to think. Believers have an instinct about how and what they believe. The primary object of religions is not to create a larger more extreme bunch of converts. Religions

are effective because their believers and supporters already know where they stand, and act from that. True, CofE Anglo-Catholics and Evangelicals have spent the last almost 200 years fighting

about their title deeds and caring a great deal about what the truth really is. And Rowan is probably too much of a genuine though liberal Anglo-Catholic — a type that has been rare at

Cantuar. But for most people the sort of scruples he has manifested about using his post to advance his party — and assuming there is a kind of unity somewhere — makes no sense. His

justification for his approach to the wielding of his authority does not relate to the reality of the Anglican church in England. We are a country where betraying your friends has been seen as more

heinous than betraying your nation.

Rowan’s abandonment of Jeffrey John was by and large simply incomprehensible to most people – and indicative of weakness, misjudgment, abuse of power, and muddle-headedness. The explanation

could only be that Rowan was incapable of serious political calculation — since John was victimised for having engaged in an argument about teaching with honesty as well as subtlety. Rowan

appeared to be so much the clever academic that he was simply unable to be his own person or to think straight. We were stuck with him, and he could obviously be counted on to be always too

understanding of both sides of any argument and too naive about the partisanship appropriate to the development of convictions.

The consequence of Rowan’s playing by rules that no Archbishop of Canterbury had ever used before and that most church people have never understood has been totally bewildering. On his watch,

and quite bizarrely, the country has happily embraced the idea of civil partnerships and of women priests. Large numbers of Anglican clergy have contracted with civil partners. Yet the leader of

the whole CofE charade has been seen desperately trying to shut the stable doors long after the horse has bolted. There’s something depressingly wrong-headed about that. Surely a man who had

persuasively concluded that active homosexual relationships might be capable of being free from sin in the Christian sense owed it to the Church, and to the society that Church existed to serve, to

contribute his further insights to the development and refinement of the Christian understanding of sexuality. It is not easy to reconcile the Christian tradition on this matter. But it is now

necessary because what the Church had been teaching about sexuality, drawn from the Bible, is widely regarded as contemptible – and the sexual misdemeanours and hypocrisy of the clergy have

rendered that teaching completely insupportable.

Since the role of Archbishop is undoubtedly a political role, however much Rowan dislikes the establishment of the Church, his disengagement from all argument has undermined his authority and

effectiveness. It is a convention of the British constitution that the Queen does not let on ever what she thinks about issues or individuals. But that active discretion has never applied to her

Archbishops — especially where what Rowan has said on sexuality ‘remains on the table’ — as he has put it. He does not need to pose in this way, which has meant that he has

abdicated from providing a clearly focussed sense of direction — and hoped people would regard this approach as justified scrupulousness. But it has severely limited his influence that nobody

has really been able to be clear what his objectives were in his personal exploration and theological re-examination of the inherited Anglican Christian tradition — for which he certainly has

a powerful affection. We can appreciate much more clearly what he cares about in secular political terms than what ultimately matters to him in Church terms.

There are good reasons why Archbishops and Bishops of the Church of England have tended for the last 200 years to follow a headmasterly model, even if not — like Geoffrey Fisher — an

actual former public school headmaster (of Repton). One could describe the CofE as follows: Canterbury is HM, York deputy HM — and the rest of the House of Bishops are like public school

housemasters, with the parish clergy as sort of prefects and the laity as the boys being educated and paying the fees. The arrival of women in the house of bishops will not change things, any more

than women parish clergy have undermined the fundamentally masculine model of Anglican church order. But of course Rowan comes at all of this as an outsider — in fact neither current

Archbishop is Church of England, or specially sympathetic to what the CofE has represented or how it does its job in the English cultural mix.

The reason Rowan’s innocence of English synodical government has been so bad for him and for the Church (he was a distinguished and liked academic, from the disestablished Church of Wales who

never ran a parish or an English diocese) is that he had never had the opportunity to develop any familiarity or concern with how the CofE goes about its work or what its role really is. Most

previous archbishops (Geoffrey Fisher, Randall Davidson, even the outsider Cosmo Lang) at least went through the hard grind of doing a ‘housemaster’s’ job as diocesan bishop,

engaging with the discourse in the House of Bishops or the Lords.

I have known and, like most people, been impressed by Rowan ever since first hearing him speak at the second Loughborough Catholic Renewal conference in April 1983. Since then I have heard him

numerous times. He is a fundamentally nice and good man, with a very fine brain, and has done the job of Archbishop of Canterbury honestly and sincerely. It is true that when he talks he tends to

preach, but even at General Synod I have heard him be truly inspiring in what he says. Along with others, I campaigned for him to get the top job. I had some practical experience of him having

served on the executive committee of Affirming Catholicism from 1996 to 2002 — because Rowan helped build that by now unimpressive ‘liberal catholic’ Anglican movement in the CofE

by being one of the speakers at its launch conference in 1990 at St Alban’s, Holborn. And in 1999 I got him (as then Archbishop of Wales) to chair its ‘millennial’ appeal for

funds.

Rowan is a strange mixture of lefty and liberal, the former instinct leads him to believe in prescriptive egalitarian social solutions, the latter relates to how he interprets language and faith

— where he can seem progressive or unprescriptive or elusive about what is actually meant by a doctrine or a teaching. For him spirituality would seem to be the poetry of faith: he appeals to

Christians with liberal instincts because doctrinal in a literal sense. Language is the stuff of philosophy and theology, and when Rowan distinguishes between the God he believes in and sundry

other interpretations of what God is thought to be and to want from us, it is easy to conclude that Rowan is ‘on the side of the angels’ — that indeed he shares one’s view

(whoever one may be). Perhaps that is a useful pastoral gift, seeming onside.

The General Synod has often given Rowan standing ovations and warm endorsements perhaps mainly because the theological language he uses is nebulous or ambivalent enough to make a wide variety of

religious-minded people feel comfortable (being ‘inclusive’ is an Anglican mantra, though more of a myth than reality). However, it is much much rarer for the Synod to actually do what

Rowan says he wants, or vote the way he wants — because he usually draws back from that sort of leadership exercise. Often it is unclear how passionately he is committed to getting something

through. When both Archbishops suggested the women bishops Measure needed to be revised and made more user-friendly for conservatives who will never accept women bishops, the House of Clergy took

not a blind bit of notice. Rowan stated what he thought — but implied that others should make their own minds up, which is not how generals win battles or headmasters maintain a

school’s orderly sense of direction.

I thought I probably knew what kind of Archbishop he would be — less of a witty diplomat than Runcie, but as convincing in his well-articulated spirituality and vision as Michael Ramsay.

However, when I sent him a card from the Starnberger See in summer 2002 congratulating him on taking the job, I wrote that I well knew he would have to displease a number of his supporters in this

new role. I felt he would not proceed as his predecessor George Carey had done — politically blinkered and working exclusively for his own ecclesiastical party (in Carey’s case fairly

conservative Evangelicalism). I did not expect him to abandon the causes in which he had seemed to believe — as he has done — in order to play the chairman above the arguments. I also

did not appreciate how very little he understood or related to the Church of England.

Comments