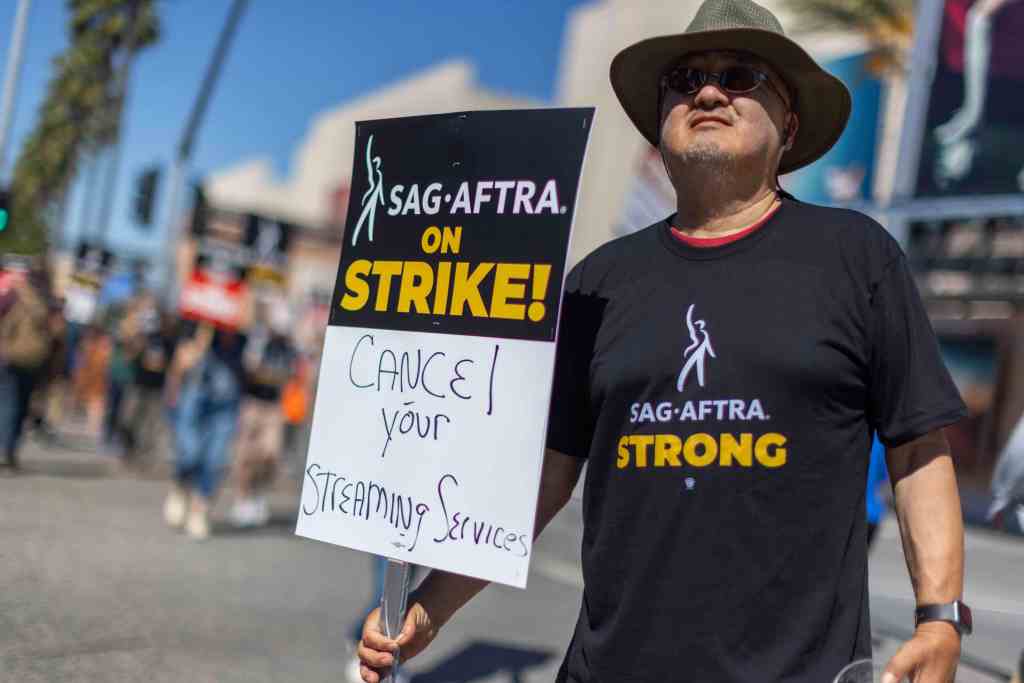

For the past week Hollywood’s film and television actors have been on strike, plunging Los Angeles’s most famous industry into chaos. Performers joined screenwriters (who have been striking since May) on the picket line after talks broke down in what has become the first simultaneous strike in more than 60 years.

The strikes have attracted plenty of headlines, not least when the cast of Oppenheimer walked out of its UK premiere last week. But do we really care if studios have to shelve Fast and Furious 15, or if the latest superhero movie fails to take flight – or indeed if the entire cocaine-encrusted edifice crumbles into the Pacific Ocean?

Hollywood has been a busted flush ever since the moguls decided the only way to maintain their mansions was to appeal to the least discerning demographic, namely hyperactive teenagers

The truth is, Hollywood has been a busted flush ever since the moguls decided the only way to maintain their mansions was to appeal to the least discerning demographic of all, namely hyperactive teenagers. Bar the odd patronising ‘heritage’ movie designed to make old people feel fuzzy, studios gave up on adult audiences a long time ago.

As grown-ups we demand involving stories that move us in some way; far easier and more lucrative for the studios just to give the kids more of what they want. Those grim out-of-town multiplex cinemas have come to resemble industrial units where young, concentration-averse brains are loaded with buckets of sugar while being blasted with 89 minutes of epilepsy-inducing ‘product’.

Up until the pandemic the studios remained cock-a-hoop – millennials were their most lucrative audience yet, and while producers still relied on star quality to bring in the punters, with AI that could all be about to change. The formulaic nature of so many Hollywood scripts means that AI can rustle up a half decent action movie in the time it takes a real screenwriter to question their integrity. And when storylines depend more on an actor’s ability to look convincing against a green screen than their talent for reflecting the sad complexity of human existence, why not dispense with them too?

There’s no doubt the pandemic hit the industry hard. Veteran media analyst Michael Nathanson says: ‘The economics of the industry are very challenging – the worst that we’ve ever seen.’ With wages plummeting and the streaming giants haemorrhaging subscribers, is it any wonder Tinseltown has lost its sparkle?

Fran Drescher, president of SAG-AFTRA – the union that comprises the Screen Actors Guild and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists – reflects the sombre mood of her union members. ‘The entire business model has been changed because of streaming, digital and AI,’ she says. ‘At some point, you have to say “no, we’re not going to take this any more”.’ For ordinary writers and performers it’s a mess – but for the moneymen the latest technological breakthrough couldn’t have come at a better time for an industry in severe decline.

The strikes now affecting production feel a lot like the denial stage of the grieving process, with creative types angrily refusing to accept that the technology they once dismissed as a joke has finally caught up with them. Yes, the future of the entertainment industry looks uncertain, but what these poor loves fail to grasp (or more likely choose to ignore) is that the Hollywood fat cats with whom they are clashing couldn’t give a flying picket about their plight. The Burbank bean-counters’ only concern is the bottom line and whether the multiplex kids they have come to rely on will notice or even care if a favourite action hero is replaced by an artificially intelligent counterfeit.

I have watched those remarkable clips of a deeply faked ‘Tom Cruise’ and am frankly flabbergasted by the uncanny realism on display; extraordinary to think we are witnessing, in real time, that long-anticipated moment where reality and fakery become indistinguishable. While older film buffs may question the ethics of the great talent replacement, younger audiences who have grown accustomed to interacting with lifelike video game characters may simply shrug and move on.

Performers are being naïve if they think they can hold back what looks increasingly like an unstoppable tide. For now, it is only background artists suffering the indignity of full digitisation, but as AI expands should we really expect studios to continue paying flesh and blood stars when digital doppelgangers can do the same job cheaper and more efficiently and without the need for Botox and stretch limos? Think about it: Tom Cruise turned 61 this month, meaning his days as a pretty boy action hero are numbered; Harrison Ford is 81, meaning retirement can’t be far off. Mission Impossible and Indiana Jones have been spectacularly successful franchises – why should they have to end, the studios might argue, just because the original actors are no longer on the payroll?

At the premiere of the most recent Indiana Jones movie Ford spoke of his concerns for the future of the industry: ‘What scares me about AI is when it begins to pretend to be a creative opportunity.’ Well, Indy, that day is nearly upon us and no amount of hollering is going to make the future go away.

When asked about the secret of good acting, Noel Coward famously snapped: ‘Say the lines and don’t trip over the furniture.’ If AI has its way, actors won’t even need to worry their pretty little heads about that.

Comments