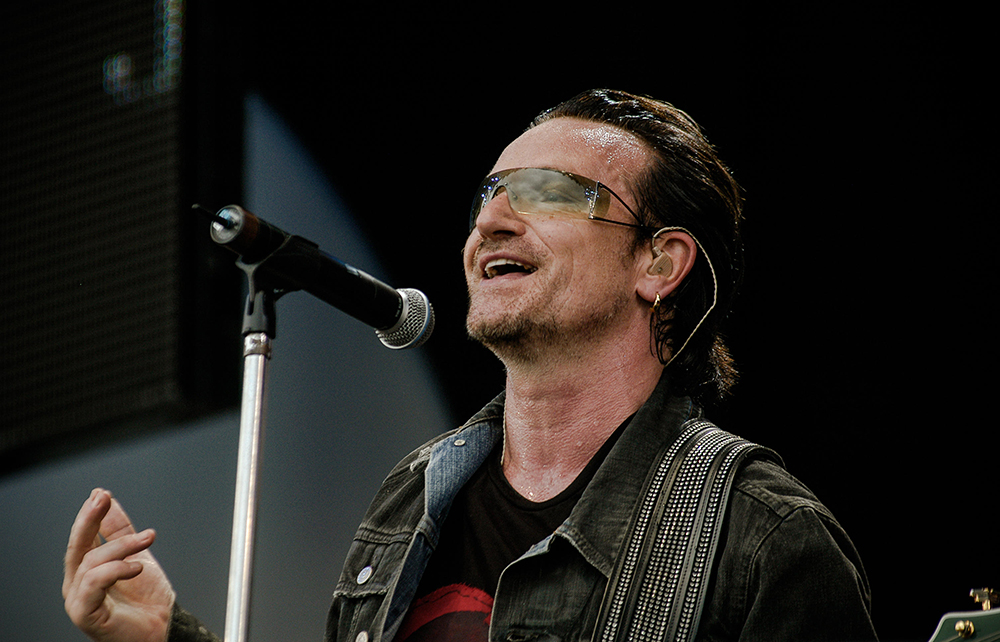

There are a few pop stars whose work I can’t help liking in spite of myself – their song-writing, that is. I’d be happy never to see the faces or hear the voices of Mick Hucknall or Chris Martin again, but the moment ‘Stars’ or ‘Trouble’ starts, I’m mesmerised – only to wonder crossly the minute the song ends: ‘Why couldn’t they have given it to someone with a decent voice?’ Think about it: dancers have choreographers and actors have scriptwriters, so why should we assume songwriters can sing? Bono’s another. I love some of his songs (‘One’, as performed by Johnny Cash, and ‘Where the Streets Have No Name’, by the Pet Shop Boys), but when faced with the awful actuality of his yowling, I remember what Prince once said about him: ‘You know what I’d do with a voice like that? Become a janitor.’

Surrender comes in at a whopping 563 pages, and I was already beginning to feel quite enervated by the time I’d read the press release informing us that Bono is an ‘artist and activist’ who has written an ‘honest and irreverent, intimate and profound’ book – which we’re lucky he got around to, considering his ‘more than 20 years of activism, dedicated to the fight against Aids and extreme poverty’. But isn’t having your press release calling your book ‘profound’ rather like giving yourself a nickname? Wait for someone else to do it.

Nevertheless, I dived in, and I can’t say I wasn’t entertained. The book reads mostly like a Craig Brown parody rejected by Private Eye for being too cruel. I considered underlining the most annoying passages for future reference before realising it would be quicker to highlight the bits that weren’t annoying. Suffice it to say I learned this from the first five chapters:

1. Bono has a different heart from the rest of us. (Did you doubt it?) The book starts with him on the surgeon’s table, his special heart having been ‘stressed’. But never mind. ‘We needed extra-strong wire to sew him up – he’s probably at about 130 per cent of lung capacity for his age,’ the awed sawbones tells Mrs Bono.

2. At 18, Bono had read Crime and Punishment – but he prefers the Ramones.

3. Aged 11, Bono already loved music, but, mysteriously, his mother told the principal of his new school (famous for its choir) that he had ‘no interest in singing’.

4. Bono’s father had a lovely voice and enjoyed performing opera; but when Bono sang, his dad ignored him. (Do we see a pattern here?)

5. The teenage Bono was so sexy that even trees became seductive in his presence.

There are so many unintentionally comic lines in this book that it’s hard to choose those which best sum up the bombastic force of the author’s ego. The loose, colloquial style is meant to be charmingly chummy, but it feels more like getting cornered by an arch bore at a party. So we have matchless gems such as: ‘I had a recurring voice problem.’ I particularly like the eyes-of-a-child shtick (Bono is keen on posing as a naif, as the ghastly drawings which accompany each chapter prove) when he walks with the mighty and accepts them as regular folk: ‘Warren Buffett might have become the richest man in the world’, but ‘the Sage of Omaha was still as real an American as you could hope to meet. He drove himself to our opening night.’ And: ‘There’s something in Rupert Murdoch of his presbyterian preacher grandfather.’ George Soros scolds: ‘Bono, you have sold out for a plate of lentils.’

Bono certainly talks a good redemption, but does he walk the walk?

Whether you’ll find this book endearing or irritating will depend mainly on whether you buy Bono’s basic USP: Good Guy in a Bad World. He certainly talks a good redemption, but does he walk the walk? His relationship with his vast wealth does not bear close inspection. He has avoided paying millions in tax in Ireland by moving U2’s royalties operation to the Netherlands. He set up an ‘ethical’ fashion label ‘to encourage trade with Africa and celebrate the possibilities and people of the continent’, and then moved the business to China, and was accused by the campaign group Debt and Development of robbing the world’s poor by stashing huge sums in a tax haven when the revenue might well have been used for overseas aid.

I’m sure Bono would deflect such criticism by putting his hand up and calling himself a sinner – of course he would, it’s so rock’n’roll – and indeed he gallantly claims to have been rescued by his wife: ‘This is the story of how Eurydice saved Orpheus… the story of how Alison Stewart saved me. From myself.’ The implication is that our humble hero would have been a right old Mr Lover-

Lover Man had he not been bagged by Alison as a teenager (‘I’d developed a bit of a reputation as a man around youth clubs’ – pure Alan Partridge). But being bad isn’t about how much money you put it about; it’s about putting your money, where the poor that you’re such an ‘activist’ on behalf of, can’t feel the benefit.

Similarly, Bono would like us to believe that he is ‘passionate’ about politics. But there’s nothing here on how Ireland has become one of the worst places in Europe to be a spirited woman or a lover of free speech, and where Christian teachers are jailed after refusing to lie about biological sex. Maybe it’s a mercy. When he tries to tackle serious subjects he can’t help but come over all Kumbaya. Writing about the Islamist massacre of young music fans at Paris’s Bataclan theatre in 2015, he beatifically concludes:

Though Islam may be uncomfortable with certain aspects of modernity, it is not a hostile force in the world. At its heart is service to the community above the individual. Islam. Salaam. Arabic for peace. Peace through surrender.

His prose reminds me of Michael Jackson’s face – the result of what happens when a pop star is so big that those who should be advising him that less is more are too cowed to do anything except indulge him. The following pearls are all too typical of the blather which distorts what could have been an interesting (and much slenderer) volume:

I love this oceanic feeling

Amniotic

Hypnotic

Some kind of underwater drum

A tom-tom

Ba bum ba bum ba bum ba bum ba bum.

I don’t believe Bono is a bad man. I think he means well. But he has mistaken himself for a great rock star, and convinced millions that he is. As he’s sold so many records, it’s an easy mistake to make. But to qualify as great, rock stars must be either sexy (Elvis) or profound (Dylan) or both (Deborah Harry). Of course it’s lovely to see people recognise their dreams, but couldn’t Bono have done it a bit more quietly? As I closed this book, I couldn’t help imagining a parallel life for him – as a janitor, happily humming the sweetest secret tunes in the whole of the Emerald Isle.

Comments