You could be forgiven for thinking you’d inadvertently turned back the clock. Cross the threshold into the majority of British schools and what appears to confront you is a workforce of unmarried women. Surely it’s 1904 not 2024, and teaching is still a spinster’s business? For, in the average 21st-century school, each and every woman teacher – married, unmarried, divorced, celibate, cat-loving, asexual or simply overworked – is addressed by her pupils as ‘Miss’.

The problem comes when ‘Miss’ is more than linguistic laziness. Could it in fact imply contempt?

I’m not talking about ‘Miss’ as a regrettable replacement for a name, as in ‘I asked Miss for some lined paper’, though that’s bad enough. I’m referring to the translation in pupil speak of Mrs Brown to ‘Miss Brown’, Mrs Bentley to ‘Miss Bentley’, Mrs Clark to ‘Miss Clark’, and so on. This is not new-wave feminism, a trendy revisionism by which any woman with a PGCE proudly takes ownership of the once-despised single-woman’s title. Neither is it prompted by historical empathy, a way of expressing solidarity with the forgotten legions who previously forfeited both their jobs and financial independence when, recklessly, they chose to marry. On the contrary, it’s something mostly outside the control of the women teachers in question (though many appear acquiescent, indifferent or both, presumably ground down by years of Ofsted’s silliness, slashed budgets, leaking classrooms and downwardly mobile teenage happiness levels).

The new Misses are not crusaders. These are not women happy to shed their spouses in the workplace and stand and be counted alone, confident of expertise unconnected to their emotional, domestic or sexual arrangements. Rather, the modern Miss is a victim of teenage diction. It’s simple: children can’t or won’t pronounce ‘Mrs’. They call every woman with a mark book ‘Miss’.

It may be laziness. It may just as easily arise from indifference, informality or ignorance. Thanks to current debates about gender, the significance once associated with titles now belongs to pronouns: ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘they’ are more pressing distinguishers than yesterday’s ‘Miss’, ‘Mrs’, ‘Doctor’, ‘Dame’. Anyway, in a first-name culture, does it matter? It’s 2024 and everyone’s Dave, Daisy or Dorcas, regardless of age, eminence and the closeness or otherwise of the relationship between speaker and object. In this chummy world even the monarch is invariably referred to as ‘King Charles’ instead of the loftier, more remote-sounding ‘The King’. And perhaps, for a growing majority of those of pre–marriage age, there’s genuine confusion about the difference between the similar-sounding Miss and Mrs.

So is it important? Few women in western democracies are brought up to regard marriage as an achievement that merits trumpeting in all contexts. As a profession, teaching can claim to have used language to promote gender equality – witness the horrible ‘headteacher’, which has so ruthlessly muscled aside ‘headmistress’ and ‘headmaster’ – so a one-size-fits-all feminine descriptor that ignores distinctions in partnership status can be seen as an aspect of this non-discriminatory work culture.

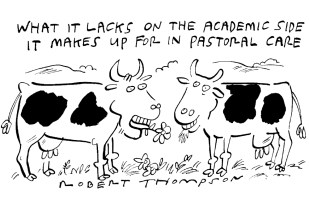

In a country where the gulf between state and independent schools sometimes appears alarming, there’s also a democratic universality about this ‘Miss–supplants-Mrs business’, which is as widespread in smart boarding schools as in those edgier establishments that inspire television documentaries. (The all-boys boarding school that refers to all women teachers as ‘Ma’am’ is obviously an exception; applied to everyone, Ma’am is as non-individualised as the universal Miss, and it’s possible that there are women teachers who don’t wish to be considered either American or royal.) The problem comes when ‘Miss’ is more than linguistic laziness. Could it in fact imply contempt, suggesting that, in the opinion of her pupils, the hapless operative in charge of the classroom oughtn’t to have stood a cat in hell’s chance of bagging any sort of life partner?

For the foreseeable future, women teachers have no choice but to accept a development that seems to defy reasonable explanation. This isn’t a condition treatable on a case-by-case basis. Children who have never managed ‘Mrs’ won’t manage it for any one affronted married woman, however forceful the particular woman. Only joint action will suffice. And teaching unions may feel they have more pressing issues with which to contend.

In 1927, at a time when women teachers still lost their jobs on marriage, the Times Educational Supplement was moved to reassure its readers: ‘The woman teacher who marries has not lost the benefit of her training or experience.’ That such a statement was necessary possibly lessens the irritation of current permissive Miss-ishness. If women teachers are always officially unmarried, each of them ‘Miss’, there can be no question of losing their hard-won benefits.

Comments