The police initially treated last weekend’s stabbings on a train near Huntingdon as a possible terror attack, before confirming it wasn’t. Since then, it has been widely reported that the suspect, Anthony Williams, told one of his victims that ‘the devil’s not going to win’ as she pleaded with him not to stab her. So instead of terrorism, the outlines of another familiar British tragedy have begun to take shape: a violent outburst by a man apparently in the grip of severe mental illness.

Why would someone with severe mental illness be able to roam in public? It is partly because of underfunded public services. The number of mental health beds in the NHS decreased by a quarter between 2010 and last year. A psychiatrist weighing up whether or not to section a potentially dangerous patient has to wonder where they would be put. A survey this year from the Royal College of Psychiatrists found that almost three-quarters of respondents said they had made an admission or discharge decision ‘based on factors other than the patient’s clinical need’.

The cost to the state of sectioning is enormous. A psychotic patient may require round-the-clock supervision. In 2023, the average cost of outsourcing a single patient to a private mental health provider in Northamptonshire – often a necessity due to lack of capacity – rose to just over £700,000 a year.

Another change has been more ideological: the shift towards treating severe mental illnesses within the community instead of within institutions. This began in 1961 when the then health secretary Enoch Powell delivered his ‘Water Tower’ speech, in which he denounced the old Victorian asylums as ‘isolated, imperious’ and ‘majestic’. Over the following decades, Britain dismantled almost all of its long-stay asylums. The 1983 Mental Health Act formalised that shift, embedding a rights-based model that prioritised voluntary treatment and deinstitutionalisation. This progressive trend has continued virtually uninterrupted ever since.

The case of Valdo Calocane in Nottingham in 2023 should have caused a reckoning with the country’s unwillingness to properly resource acute psychiatric care. Calocane, a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic who killed two university students and a school caretaker in random stabbings, had been detained in a psychiatric unit four times in two years. A Care Quality Commission review concluded that there were ‘systemic issues with community mental health care which, without immediate action, will continue to pose an inherent risk to patient and public safety’. The families of those murdered went further, saying that the professionals involved had ‘blood on their hands’.

Axel Rudakubana, who murdered three young girls in Southport last year, had been known to local child mental health services since February 2021. In March 2022, Rudakubana told police officers who found him on a bus with a knife that he wanted to kill someone. He was discharged from mental health services two years later – six days before the murders took place. The parents of Elsie Stancombe, killed at the age of seven, said their ‘daughter paid the price’ for the failure to take action.

Zephaniah McLeod, a paranoid schizophrenic who stabbed one man to death and injured seven others in September 2020, had told a psychiatrist two years earlier that he was hearing voices that said: ‘Kill ’em, stab ’em, they’re talking about you.’ The mother of the dead man said: ‘My son bled to death in the street at the hand of someone well known to many agencies.’

At each inquest, the same phrases recur: ‘known to services’, ‘failing to take medication’, ‘missed opportunities’. And yet the structural problems remain. What’s more, Britain’s mental health establishment is, in some respects, taking steps to worsen them.

Over the past ten years there has been a political demand to reduce sectioning, particularly in regards to black men and people with autism and other learning disabilities. Labour’s 2024 manifesto promised to ‘modernise’ the 1983 Act. This has resulted in a Mental Health Bill, introduced in the House of Lords in November last year and making its way through parliament. One element of the modernisation plan relates to ethnic disparities. The Labour manifesto stated that the system ‘discriminates against black people’. Black people in England are around three and a half times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act, and seven times as likely to be placed on a Community Treatment Order.

Each time the same phrases recur: ‘known to services’, ‘failing to take medication’, ‘missed opportunities’

Within the NHS, the fear of discrimination is already institutionalised through the recently introduced Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework, which every mental health trust must implement. It obliges them to publish data on racial disparities and set out plans to narrow them. The problem with this is obvious: clinicians who are incentivised to shrink ethnic gaps in sectioning rates risk overlooking cases of severe mental illnesses among black patients.

This could have deadly consequences. Black men are ten times more likely than white men to screen positively for a psychotic disorder. The causes are complex and uncertain: socioeconomic deprivation and drug use may be in part to blame. But dealing with disparities through equality targets, instead of addressing the root causes, will ultimately endanger both public and patients.

Another element of sectioning which the government is determined to change relates to patients with learning disabilities and autism, the treatment of whom the Labour manifesto described as ‘disgraceful’. The Mental Health Bill will prevent people with learning disabilities or autism from being detained under the Mental Health Act solely because of those conditions. Campaigning charities such as the National Autistic Society wish for these patients to be dealt with in the community, but the Royal College of Psychiatrists points out that when it comes to those primarily experiencing learning disability or autism, ‘there are times when community services are unable to manage the levels of risk some patients present with’. It seems this warning will be ignored.

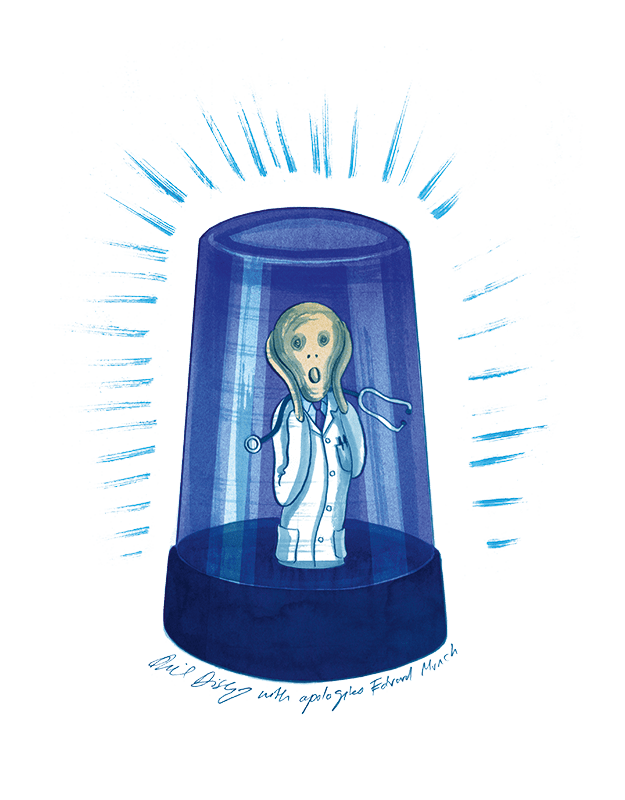

Dr Max Pemberton, a psychiatrist and Spectator contributor, tells me that the threshold for sectioning has increased significantly over the past ten to 15 years. Now it is ‘almost impossible’ to get somebody sectioned. He describes an ‘ideological shift to community care’ which he believes is motivated by pressure from both charities and politicians, as well as a desire among NHS bureaucrats to justify reductions in mental health beds. The threats posed to patients and the public by the raised thresholds for sectioning make him ‘incredibly anxious’.

Compassion for the mentally ill is essential, but compassion that excludes the innocent victims of untreated psychosis is sentimentality disguised as ethics. What needs reform is not the Mental Health Act but the state’s ability to provide enough beds, staff and places of safety so that doctors can detain individuals according to their professional judgment, without fear of litigation, cost pressures or ideologically driven equality targets.

It is easy to simply call for more funding for the NHS. Politicians should instead look at what measures can be taken to reduce demand on mental health services. None is easy. Unofficial acceptance of the possession of illicit substances – particularly cannabis, for which there is growing evidence of a causal link with psychotic illnesses (as Harriet Sergeant discusses in these pages) – may have to change. The over-diagnosis of mental illnesses must also be curtailed. The percentage of adults aged 16 to 74 with a common mental disorder who are receiving treatment has more than doubled since the turn of the century. This socio-cultural phenomenon creates unsustainable pressure on mental health services and is also a primary cause of the modern worklessness problem through the welfare system, further starving the state of resources.

Difficult though these changes will be, radical thinking is warranted when the alternative is the de facto rationing of treatment for severely mentally ill people and the subsequent threat to public safety. Reform which does not address the supply and demand of psychiatric care simply means fewer dangerous people sectioned – and more people stabbed.

Comments