When I started working for Vanity Fair in 1995 I remember coming into the office one morning to discover that most of the senior editorial staff had disappeared. They weren’t at their desks, and phone calls went unreturned. Was this a Jewish holiday? It turned out to be the day Graydon Carter had set aside to write the ‘Editor’s Letter’, a monthly column at the beginning of the magazine signed by him but which he almost always asked one of his staff to write at the last minute. None of them wanted to be the poor schmuck saddled with the task.

The reason I mention this is because the previous book Carter ‘wrote’, a series of gripes about the George W. Bush administration, was a loosely stitched together collection of those letters. Which raises the question: which down-on-his-luck hack was roped in to ghost When the Going Was Good?

Below Graydon’s name on the title page are the words ‘with James Fox’, which sounds like the answer. But in the acknowledgments, Graydon says ‘The writing is mine’, and thanks Fox for ‘guiding me along the narrative path’, whatever that means. He adds that he and Fox were ‘assisted’ by Hannah Lack, as well as by a former colleague, Cullen Murphy: ‘He edited my copy when we were at Vanity Fair’ (he wrote the ‘Editor’s Letter’, presumably) ‘and he edited this book.’ Graydon then thanks a fourth person, Ann Godoff, his editor at Penguin Random House, who gave the manuscript ‘a skilled and spirited edit and polish’.

A few pages into what Graydon calls ‘this slim volume’, I began to think that the real author might be Craig Brown. The book reads like one of Brown’s pastiches in Private Eye stretched to 432 pages. Take this passage, in which the celebrated magazine editor describes a party the day after he announced his departure from Vanity Fair:

We also had a long-planned dinner the next evening with Sherry Lansing and Billy Friedkin, along with Candy Bergen and her husband Marshall Rose. Sherry couldn’t get over the fact that the story of my stepping down from the magazine was on the front page of that morning’s Times. ‘Graydon, dictators get the front page when they step down!’ Many days I look back on her statement and take it as a compliment.

That name-dropping followed by humblebrag is typical of the man I knew in the mid-1990s, and I congratulate the four-person ghostwriting team for having captured him so well. Or perhaps it really is his own work. I know Fox isn’t the literary journalist he once was, but could he really bring himself to write a series of sentences like the following?

When travelling on business, I stayed at the Connaught in London, the Ritz in Paris, the Hotel du Cap in the south of France and the Beverly Hills Hotel or the Bel-Air in Los Angeles. Suites, room service, drivers in each city. For European trips, I flew the Concorde. I took round-trip flights on it at least three times a year for almost a decade. That’s something like 60 flights. My passport picture was taken by Annie Leibovitz!

To be fair to Graydon, this is a passage about the extravagant lifestyle enjoyed by glossy magazine editors in the 25-year period he was at Vanity Fair (1992-2017), and some of the details really are jaw-dropping. Attending his first Leibovitz cover shoot, he learns that the food budget for herself and her staff for that one day was more than he’d spent on an entire issue of Spy, the satirical magazine he co-founded in 1986. Vanity Fair’s writers were paid the kind of money investment bankers earn today (Dominic Dunne was on half a million dollars a year), and Graydon not only spiked one in five submissions but paid full whack for the articles he rejected. ‘I never paid a kill fee,’ he says.

Graydon doesn’t disclose how much he was earning when he stepped down – only that when Si Newhouse, the billionaire owner of Condé Nast, suggested a starting salary of $300,000 to work for him in 1992 he told him to double it. One of the perks of working for Newhouse, he reveals, was that he offered his editors interest-free loans. Graydon appears to have taken full advantage of this, boasting of owning properties in New York, Connecticut, the south of France and London, not to mention a restaurant, a ‘fleet’ of classic cars and an aeroplane.

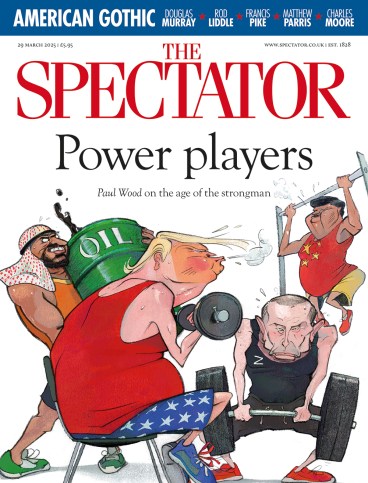

All this bragging gets quite tiresome and makes one wonder why Graydon still feels the need to impress people with what a big cheese he is. Isn’t having taken 60 trips on Concorde enough to allay his status anxiety? But he is that familiar figure from the memoirs of successful New Yorkers – an alpha male with paper-thin skin, who may remind you of someone. If the book can be said to have a villain it’s Donald Trump, whom Graydon dubs ‘the short-fingered vulgarian’, a not-so-subtle reference to his penis size, and he constantly ridicules the President for trying to rebut this allegation.

Isn’t having taken 60 trips on Concorde enough to allay Graydon Carter’s status anxiety?

Yet to anyone who’s worked for Graydon, the skewering of Trump for his myriad insecurities feels a lot like projection. During my stint as a Vanity Fair editor I recall one hapless intern finding himself sharing a lift with the boss and, because he couldn’t think of anything better to say, remarking that he hadn’t seen him around the office much lately. Graydon scowled at him, then a few days later dispatched one of his trusted lieutenants, Aimée Bell, to have a word with the chump. ‘You don’t tell one of the hardest working editors at Condé Nast that you haven’t seen him around the office much lately,’ she scolded.

One of Graydon’s saving graces – the thing that made him fun to have a drink with – was how full he was of malicious gossip about his rivals, which was the flipside of constantly bigging himself up. I remember him gleefully relaying the story of Tina Brown, his predecessor at Vanity Fair, being asked to show a documentary television crew around the offices for a segment on 60 Minutes, the prestigious CBS news programme, and getting completely lost within seconds. ‘In eight years of working there, she’d only ever gone from reception to her office,’ he said.

But, with the exception of Trump, most of the cast members here are showered with praise. Every time Graydon mentions meeting some Hollywood legend, he’s goes on to say what great friends they’ve become – unless they’re dead, in which case he tells you about his starring role at their funeral (pall-bearer, eulogy-giver). You have to go quite far down the celebrity food chain to find someone he’s prepared to gossip about. In the past 25 years, apparently, the only guests to have misbehaved at the Vanity Fair Oscar party were Paris Hilton, Harvey Weinstein and George Lazenby. Whatever the opposite of a tell-all memoir is, this is it.

In a rare moment of self-deprecation Graydon quotes Henry Porter, a former London editor of Vanity Fair, suggesting that he call his autobiography Magna Carter: How to Be More Like Me – which would have been a better title for this book. There’s a compilation of Pooteresque advice in the final chapter – ‘Always carry a handkerchief’ – and scarcely a page that doesn’t contain some supposed pearl of wisdom, often directed at would-be magazine editors. Which is odd, considering the book reads like an extended lament for the golden age of magazines, with Graydon convinced we’ll never see their like again.

The lesson I learned from him during my two-plus years at Vanity Fair is that dealing with the rich and famous on a daily basis is a ‘pride-swallowing siege’ (Jerry Maguire), unless you are as egotistical as them. Indeed, behaving like a sacred monster is often the only way to earn their respect. Perhaps that’s why Newhouse showered his top editors with so much gold, knowing that the only way to entice people like Tom Cruise and Demi Moore to pose for his magazine covers was to create some stars of his own and send them out to seduce them. In Graydon, he found his Norma Desmond, and the subtext of this book reminded me of her great line from Sunset Boulevard: ‘I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.’

Comments