Is the EU-China investment deal dead? It was last week sunk down by 599 votes to 30 in the European Parliament, but that’s not being taken very seriously in Beijing if the national press is anything to go by. China’s state media is a fair proxy for what the famously opaque ruling party is thinking, and it has been calm in its analysis. All this offers an interesting insight into how China sees Europe.

For China’s press, European protests – even the vote – are just hot air. It points out that background work on the deal continues to go ahead. So the legal text for the supposedly dead EU-China deal is still being reviewed, finalised and translated into the EU’s 24 official languages – which will be early next year. By which point, Emmanuel Macron will be holding the European Council presidency. ‘I expect that the conversation surrounding the deal will return to impartiality and rationality’, said Zhou Xiaoyan, an Tsinghua University academic commented to Xinhua News Agency.

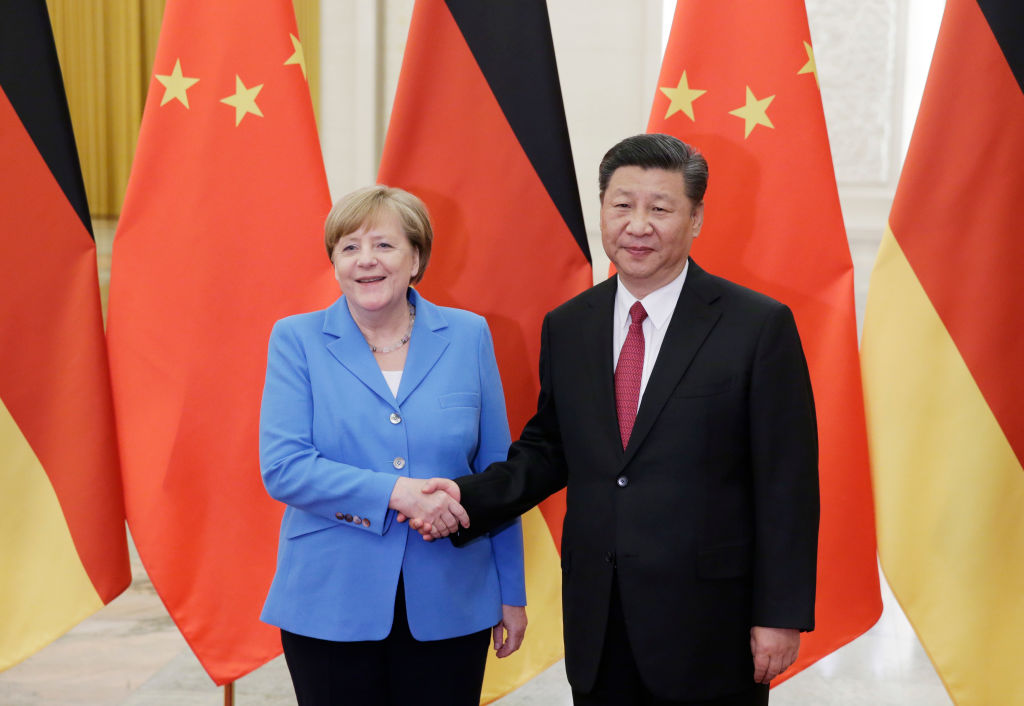

The feeling in China is that, for all of the drama in the European Parliament, the French and Germans want this to go ahead – and will get their way in the end. ‘It must be said that Germany’s understanding of the situation is much deeper than many European countries’, one writes, and ‘Thankfully, one EU country has maintained its rationality’, another said. In China, Angela Merkel has long been respected as a stable politician with the right priorities – i.e., not one to let a fuss about human rights get in the way of a good trade deal. Her campaign for building another massive gas pipe to Russia, Nord Stream 2, has come in defiance of outrage in the European Parliament. This will be closely followed in China.

But there is one threat. The incisive business paper, Caixin, points out that Merkel will soon be gone – and perhaps replaced by the Green Party’s Annalena Baerbock. ‘The vocal German Greens, who have been quite critical of the investment deal, may well be part of Germany’s next government, if not the leading coalition partner,’ it says. She certainly is vocal, having initiated an European Parliament resolution condemning human rights violations in Xinjiang, which paved the way for the EU’s sanctions on Chinese officials earlier this year.

China has always had trouble understanding why human rights concerns should play a part in trade talks or foreign policy at large. The commentary in state media assumes that leaders have to go through the motions, perhaps to assuage a domestic audience, but will ultimately seek a deal with Beijing. This mercantilist view risks underestimating the genuine strength of feeling over the Xinjiang issue. This might go some way to explain why China slapped sanctions on such a cross-section of British and European politicians. What was seen as a counter-productive move in the West makes more sense if you think, as the Chinese do, that human rights concerns are just noise in international trade.

For years Beijing has done well out of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s foreign policy maxim of ‘hide your strength, bide your time’. The CCP may not be keen on hiding its strength anymore, but when it comes to this investment deal (already seven years in the making), it is willing to bide a little more time. It is betting that, in the end, money will speak loudest in Europe. At the end of the day, it may even be right.

Comments