It’s not hard to understand Boris Johnson’s dilemma. He will hate the idea of a second lockdown, but his scientific advisers tell him it’s the best way to fight a second wave. He’s not sure if their fears are exaggerated, but how is he to know? There are not very many expert voices around No10 to challenge the SAGE committee’s assumptions.

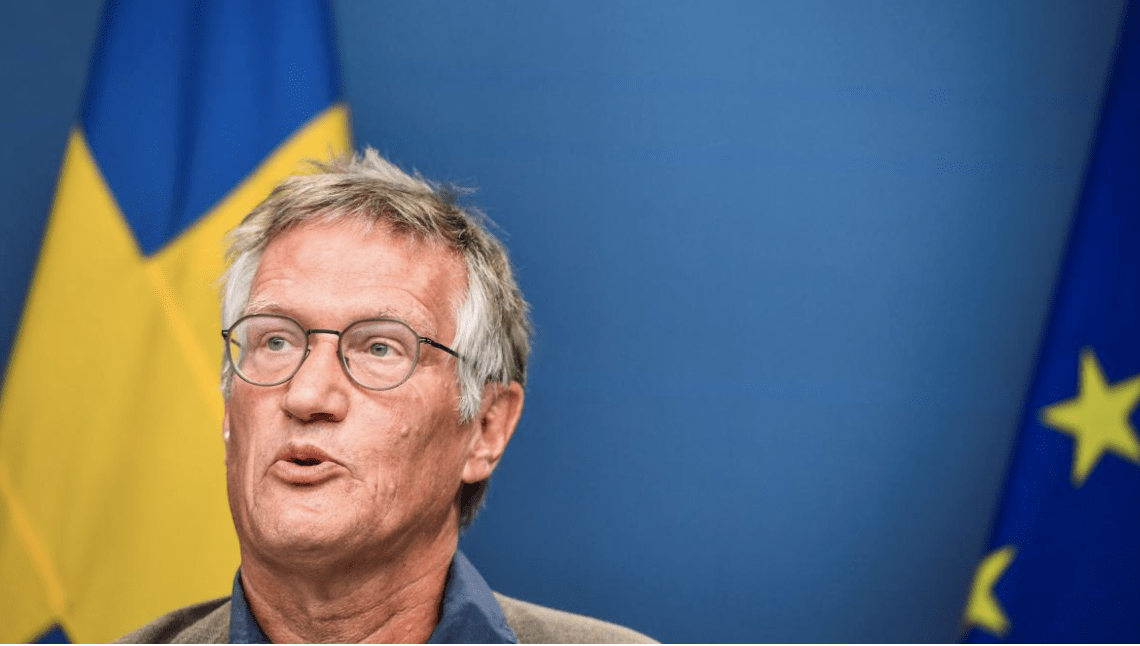

One idea could be reaching out to Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s chief epidemiologist, who has just been interviewed by Andrew Neil for our new Spectator TV. The Swedes were able to identify the exaggerations in the Imperial College London assumptions first time around – and might be able to check the assumptions No10 is being given this time.

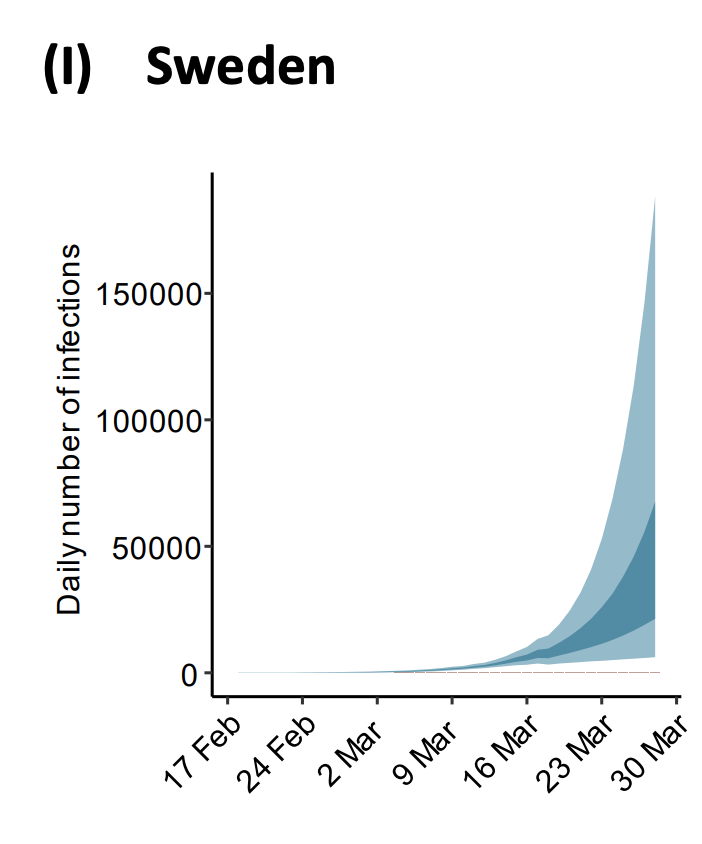

Sweden’s public health authority is well-stocked with experienced epidemiologists: Tegnell has experience in the field with Sars and Ebola and has seen first hand the problems of modelling. When Neil Ferguson’s Imperial College model was published, its verdict for Sweden was grim “Because no full lockdown has been ordered so far,” it said, the virus had kept growing exponentially in Sweden with a R-number of 2.6: ie, every infected person gives Covid 2.6 others. It’s a terrifyingly fast rate of growth – or would have been it been accurate. Swedish academics were quick to observe that Imperial’s assumptions pointed to 85,000 deaths (see note below).

But Tegnell didn’t buy it. His Public Health Agency had enough in-house expertise to spot the flaws in the Imperial College assumptions and came up with other figures which confirmed their refusal to lock down. And they were vindicated: Sweden had a problem in care comes but for society at large the virus had already been pushed into decline – never to surge again. In the end, Sweden has seen fewer than 6,000 deaths, almost half of them in care homes.

As Tegnell told Andrew Neil on Spectator TV:

“We looked at the [Imperial] model and we could see that the variables that were put into the model were quite extreme… Why did you choose the variables that gave extreme results? So we were always quite doubtful. We did some work on our own that pointed in quite a different direction. In the end, it proved that our prognosis was much closer to the real situation. Probably because we used data that we felt we could understand and coming from the actual situation, and not from some kind of theoretical model.”

Andrew Neil asked Tegnell if he’s saying of the Imperial model: rubbish in, rubbish out. He replied

“You have to be very careful about models. They’re not made to do prognosis, they are made to test various different kind of measures to take, to see what kind of effect they might have. Because as you said: rubbish in, rubbish out.”

Andrew Neil then this makes him wonder if the UK government interrogated the Imperial College data to the same degree that Tegnell did. “Yup. I think that’s a good question for somebody to look into in the future,” he replied. But then he made an intriguing point:

“If we could have more openness, and we could have had some more discussion on a technical level between countries before these decisions were taken, I think we could have arrived at something – together – that would have worked better than the situation we have right now.”

Britain is talking about a second lockdown and Chris Whitty, the Chief Medical Officer, wandering around Whitehall with studies and extrapolations that look a lot like the Imperial College London assumptions of yore. Given Ferguson’s track record, it might make sense for No10 to call up Tegnell and ask for a second opinion. Yes, Sweden and Britain are very different countries– but it’s the technical assumptions behind the models that matter. To compare notes on the basic behaviour and characteristics of the virus, and to have a frank conversation about how useful desk-based models really are. Tegnell indicates in his interview that he is open to working with the British authorities: No10 could do a lot worse than ask him to sense-check the assumptions Ferguson and Whitty are providing now.

PS As is now traditional, Imperial College has been in touch to distance itself from the 85,000 death figure saying it was made by other academics and that Prof Ferguson did not extrapolate his figures for Sweden. So it’s saying, in effect, it may have produced the below graph for Sweden but cannot be held responsible if anyone continued the graph using its published assumptions (ie: R~2.6). I’m very happy to expand on this point, because it’s important: at the time, no one knew who was right. We know more now. We know that the below graph, published on 30 March in Imperial’s Report13 was incorrect. Tegnell’s colleagues later published figures showing that Covid cases had started to fall before Imperial released its study. People changed their behaviour on a voluntary basis: as Johan Norberg says here, the Imperial model was unable to compute this. A longer analysis on on ICL and Sweden can be found here.

Comments