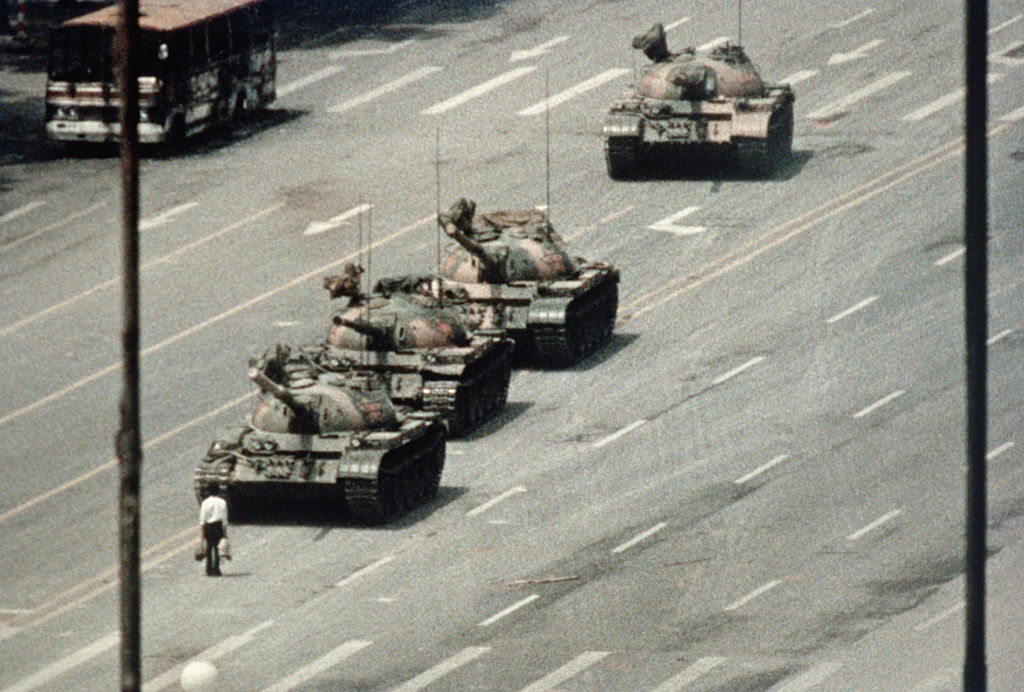

I was an argumentative teenager, and after emigrating from China to London one of the biggest rows I had with my British school friends was over Tiananmen. They’d insisted on calling it a massacre. I was adamant – it wasn’t a massacre, and the government did what it had to. Did my friends not understand that the protests had shut down the city of Beijing – not to mention other major cities across the country – for months? The protestors were a nuisance; they threatened the livelihoods of small business owners, blockaded roads, cost the country’s economy God knows how many yuan.

I didn’t back down then. But I wish I had done. To this day I blush whenever a friend dredges up that awful memory. Knowing what I do now, it’s hard to justify ever having been so naive.

My mind changed on this when I trawled through Wikipedia, trying to put pieces together and make sense of it all. The army rolled out under the orders of Deng Xiaoping, but wasn’t he to be credited with China’s reform and opening? It was in 1989, eleven years after the death of Mao. Obviously, everyone knew about the Cultural Revolution and the crazy, cruel, fatal revolutionary schemes of Maoism. In my mind, there were the dark Maoist times my grandmother lived through and the more liberal, enlightened and prosperous times under Deng that I knew as China.

So in some corner of my mind, I’d filed whatever doubt I had over Tiananmen into the ‘Maoist insanity’ drawer. I tried to find hard figures on the death toll, or evidence of the army misinterpreting their orders – for anything that absolved Deng, who I’d grown up regarding as an astute, modern, gentle reformer; someone who had been a victim of Maoism himself. So how could the reformer use the despicable tactics of the tyrant? To this day, I find this hard to understand.

It was when I visited Hong Kong university that I came across the Pillar of Shame. The blood orange structure reaches upwards, with the gruesome, suffering bodies of men and women melting into each other. It’s quite something – and especially for a memorial to exist in China at all. Didn’t Hong Kong belong to China now? How is it possible for the authorities to tolerate such monuments? On the walls, old frayed posters compared the death tolls under Mao to Stalin and Hitler. I don’t think I’d properly grasped mainland China’s radio silence on the topic until I saw what national memory should look like.

https://twitter.com/keithrichburg/status/1135787109770383360

But despite the censorship, the country hasn’t ‘forgotten’. Of course, Tiananmen is not in the textbooks, not on TV, not in film. But even in China, government power has a limit – it grates to hear broadcasters talk about today’s Chinese as being thought-controlled or suffering from national amnesia. I know young people who scaled the Great Firewall of China to find out more about Tiananmen after some teacher or parent had mentioned ‘June Fourth’ – the euphemism the Chinese use to describe the calamity. People debate and discuss it – granted, in the privacy of their homes or in quiet conversations in cafes and restaurants. No one has forgotten; it’s more that they don’t see the advantages in talking about it to a BBC reporter in the streets.

Millions of people will have come to learn about Tiananmen over there in the same way as I have done over here. But they will also ask: why talk about this to the foreign press? What is there to gain – and what is there to lose? In a one-party political system, there are more answers to the second question than are easily imagined here.

So Tiananmen is known, and mourned, in China. People just need to be careful how they do it. This is discretion, and it’s not to be confused with forgetfulness.

Comments