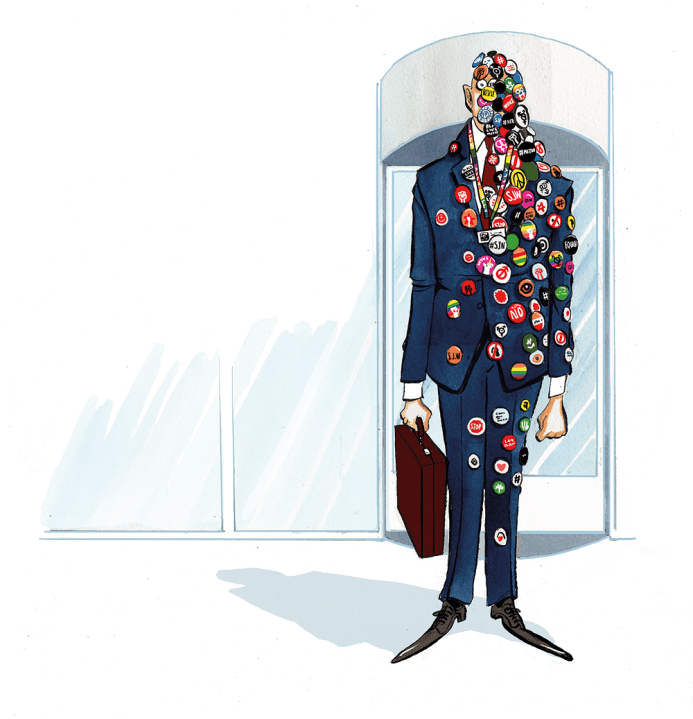

Everyone thinks they know what the Blob is. A great wobbly blancmange of Sir Humphreys and (these days) Lady Tamaras: a public sector elite, slow to action but quick to push its ideological agenda in all manner of insidious ways.

Wrong. Or rather, this is only the half of it. Whatever the gargantuan size of the state compared with pre-pandemic, what few people realise is the extent to which the private sector has been incubating its own Blob for years.

To illustrate how Blob PLC can achieve its ends and – crucially – why people have gone along with it, we must follow its successful campaign to make British business bow to the diversity gods, and how it started at the very top – with the boards.

The trouble began with Lord Davies, affectionately known in his banking career as ‘Merv the Swerve’ after the Welsh rugby no. 8 of the same name, ennobled by Gordon Brown and made a minister for business. In 2011, Vince Cable, business secretary in the coalition, published a report from Lord Davies called Women on Boards. It asserted: ‘Research has shown that strong stock market growth among European companies is most likely to occur where there is a higher proportion of women in senior management teams.’

The basis of this claim was a 2007 report by an American organisation called Catalyst, set up to ‘expand opportunities for women and business’. Not an entirely disinterested party, then. These reports, amplified later by two McKinsey studies, became the go-to texts which formed the foundation myth of Blob PLC’s diversity dogmatism.

As Alex Edmans and Ross Clark have written in this magazine, drawing on research by John Hand and Jeremiah Green in the US S&P 500 index, there is actually no evidence of a link between more diversity in a company and better stock performance.

Another of Lord Davies’s similarly baseless insights at the time was that the global financial crisis might not have happened if women had been in charge, due to their supposed lower appetite for risk. On these two commandments hang all the diversity laws and their prophets.

Naturally, boards should recruit from as wide and deep a pool as possible to increase the likelihood of finding the best people for the job. But the hypothesis that women (or indeed people of colour) bring better performance remains unproven.

Well, the wheels cranked into motion anyway. It was also widely believed at the time that the push for diversity was fashionably European. In 2005, Norway had introduced a 40 per cent quota for women on its listed boards. Twenty years later, it extended this to any private companies which employ more than 30 people.

In Britain, Lord Davies set a 25 per cent ‘target’ for women on boards, which later became 33 per cent and then 40 per cent, irrespective of the actual number of women working in corporate life at the appropriate level. The new Listings Rules issued by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in 2022 enshrined this, but they also dictated that at least one of the top four jobs of CEO, CFO, chairman and senior independent director (SID) must be held by a woman. The result was a stampede as boards rushed to appoint a female NED as their mandated SID to get around this awkward rule unless and until they felt able to put them in one of the top three jobs.

The hypothesis that women (or indeed people of colour) bring better performance remains unproven

Initially, soothing words were deployed to reassure the doubters among FTSE 100 chairmen, who would bear the initial brunt of the changes. A campaign group called the 30% Club was formed to win over the sceptics. If that didn’t work, they were pressured into compliance.

Before the target was set in 2011, Cable had threatened quotas, so targets and goals were initially greeted with relief. Veterans of nudge theory will recognise the technique, but the idea of legal quotas never went away. Just two years ago the FCA drew up plans to require all the firms they regulate to have targets for age, ethnicity, sex or gender, disability, religion and sexual orientation. Their own costing estimated this would set businesses back £561 million. After a backlash, these plans were halted in March.

Even without legal quotas, it was always a fiction that companies did not have to comply with the targets. Yes, in theory they could choose to explain why they were not doing what everyone else appeared to be doing. But, predictably, companies that didn’t comply were named and shamed. The rolling Davies review was replaced in 2015 by the Hampton-Alexander review, still supported by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, to ‘monitor progress’.

CEOs took an active role in persuading their boards to appoint more women, especially when it meant the heat would come off their own faltering attempts to diversify the workforce and senior management teams.

Even by the end of the 2010s, the corporate world had still failed to grasp that the male/female imbalance on boards was a problem not of lack of demand but of appropriate supply: women are more likely to leave corporate life early to have a family, and if they return at all, they come back too late to scale the heights.

The truth is that positive discrimination and all-female shortlists suited some women at a certain age and stage who were in no mood to be as patient as their predecessors. They took the leg up and went along with the fib that their presence would raise all boats. After all, the men had had their way for too long. There was a scramble to secure the best women on to the most prestigious boards, which meant that a small number of the best qualified women were in impossibly high demand (the so-called ‘golden skirts’).

It suited activists, equally, to believe that this was real progress. Some asserted that all this rapid change was still by merit alone. The more honest appeals to the case for diversifying the talent pool were lost in the rush to get results. Qualified men were overlooked and under-qualified women were fast-tracked well before they were ready.

Ever since 2011, these changes have coincided with the growing influence of proxy advisers, such as ISS and Glass Lewis, which had been early adopters of diversity dogma. Their role meant that passive tracker funds (that automatically invest in large stocks and do not employ their own governance teams to advise on such matters) were able to shift the tiresome burden of diversity issues from their shoulders. They automatically required the companies they invested in to adopt diversity dogma. These companies feared for their reputations as ‘good citizens’ and so our pension providers powered this diversity drive.

These trends were abetted internally by the growth of HR functions, which champion anything of this kind, and externally by their advocates in the consulting and headhunting firms, on the principle that all change is good for the order book.

The gender diversity drive was swiftly followed by full-fat DEI, for which gender had been the bridgehead. The E was for equity (initially equality, but this was magically upgraded almost overnight) and inclusion (who could be so cruel as to be against that?).

The same strategy has recently been put into action in regard to race. Sir John Parker, a well-liked panjandrum of corporate life, was asked in 2015 to lead what duly became known as the Parker Review. Result? Every FTSE 100 board was now to have at least one director from an ethnic minority by the target date (2021 for the FTSE 100, 2024 for the FTSE 250).

He used a rather watered-down justification: ‘Many of us in business would attest that our experience on boards that embrace gender and ethnic diversity benefit in their decision-making by leveraging off the array of skills, experiences and diverse views within such a team.’ This is far less dramatic a claim than had been deployed to get gender diversity off the ground. Perhaps this

is a sign of its shakiness, but it could also be a reflection of the fact that the ethnic diversity push was necessarily more modest since it involved 14 per cent of the population instead of 50 per cent. Even for the magic thinking of DEI, it would be impossible to make a strictly commercial case for the addition of one non-white director in every company.

But the push has meant that three of the four tasks about a company’s nomination committee work mandated by the Financial Reporting Council are to do with diversity.

Worryingly, today’s DEI zealots still make no mention of the need to assess and promote cognitive diversity, which in any rational world would seem to be the most important thing if you are seeking better decision-making. On the contrary, the next targets of Blob PLC – if its takeover of the public sector is any guide – will be to collect socioeconomic diversity data (what type of school you went to, your highest-earning parent’s job when you were 14) and then use it as a sifting mechanism in recruitment, removing candidates from ‘privileged’ backgrounds on the basis that this too will strengthen company performance.

If the effects of diversity targets were bad between 2010 and 2024, we can expect them to become even worse now, since Labour ministers will be fully on board with officials on such matters. There are differences between the public and private sector Blobs, but the main ideological point at which they intersect is their self-flagellating desire to ‘correct’ capitalism and atone for society’s sins.

This impulse to tell business what it is to do is chipping away at legitimate commercial autonomy and the meritocratic integrity which most people still assume (and shareholders certainly would hope) the business world stands for.

At a time when growth is needed, this is dangerous displacement activity. The private sector must see the Blob for what it is and be prepared for what comes next. The fact that this article is written under a pseudonym is evidence of the scale of the problem.

Comments