I’m in Sydney for the Voice referendum result – and it’s already over. No has won, by what looks to be a 60/40 margin. So an ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice’ will not be added to Australia’s democratic apparatus after an Aboriginal-led campaign asking Australians to reject identity politics. The results had heavy overtones of Brexit: affluent cities voting Yes and the left-behind areas voting No. The Northern Territory, which has the highest concentration of aboriginal Australians, looks to have rejected the proposal by 65/35. Aussies have voted to protect the principle of everyone being equal before the law and in parliament.

It’s hard to describe what the campaign has been like here. Corporates embraced Yes and advised their staff to vote accordingly (some have offered a day off work on Monday, to mourn the result). Sydney is draped in Yes flags put on flagpoles by the city authorities. I spent results night with a friend whose daughter had been given a Yes badge by her school to wear in class. The pressure was huge but the public refused to relent – and by a resounding margin. Anthony Albanese, who announced the Voice referendum on the day he became Prime Minister, has pledged to ‘accept the result with grace and humility’. Combined with what looks like a conservative victory in New Zealand elections, it’s quite a day for the right Down Under.

As per Brexit, the Yes side has ended up portraying it as a battle of good vs evil and ended up claiming that the No side was using disinformation and general black magic. One of the Yes campaigners, Ray Martin, observed that anyone voting No was ‘a dinosaur or a dickhead’ if they ‘can’t be bothered’ reading up on the issues. Thomas Mayo, a prominent Yes activist, attacked ‘a disgusting No campaign’ that had ‘has lied to the Australian people and I’m sure that will come out in the analysis’.

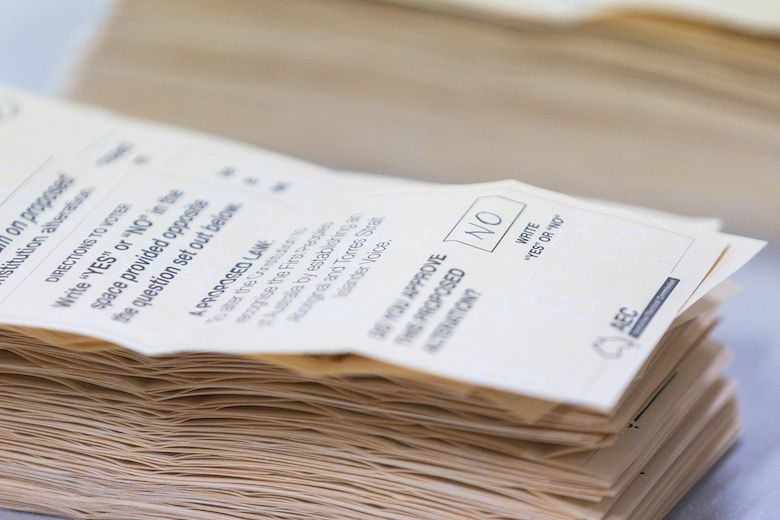

The Yes campaign never specified what form this new ‘voice’ would take. This vagueness was exploited by the No campaign, whose slogan was ‘If you don’t know, vote No’. The Aussie system of compulsory voting summoned to the ballots many of those who thought the whole enterprise a pointless distraction. But this is such a shock to the Australian system because the Yes campaign had started off expecting an easy victory. All along, Albanese could have just legislated for the inclusion of The Voice: he called a referendum because he was certain that he’d win.

The No campaign was led by Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, who we recently profiled in the magazine. Her parents, Dave and Bess, are pictured below, both speaking eloquently about the wider principles at stake. It’s a picture that sums up the No campaign’s message: one of unity. The No campaign wasn’t short of indigenous faces, challenging Albanese’s message that this was all about helping Aboriginals.

Price gave an extraordinary speech (watch it here), saying the vote showed that Australians had ‘said no’ to the ‘gaslighting, the bullying and the manipulation’ that the No supporters have been subjected to. The vote was a rejection of the idea that Australia has an original sin to absolve. ‘We are absolutely not a racist country,’ she said. ‘When we kept asking questions. We weren’t receiving any answers whatsoever.’ The No side was accused of misinformation, she said, but Yes ran ‘a campaign of no information’. The gap Australia needs to worry about is not between indigenous and non-indigenous people, she said: the Aboriginal middle classes ‘are doing very well for themselves’. The gap to focus on, she said, is that between the most marginalised and everyone else.

‘My family experienced three funerals yesterday. My family are still sitting in communities where largely they have been exploited for the purpose of someone else’s agenda. This referendum has been another one of those agendas… The Australian people were misled and the Australian people say this for themselves.’ It’s time, she said, to stop heeding ‘academics from the inner cities’ to work out what social change is needed.

One of those academics, the Yes-supporting Peter van Onselen, sums it up: ‘As someone who has advocated treaties for years, I am beyond pissed off at how badly the Yes camp has butchered its advocacy on this issue. But I won’t sugar-coat its failures and simplistically blame the No campaign for challenging the proposition. That’s democratic pluralism in action. There are legitimate reasons to vote No and anyone contemplating doing so doesn’t deserve to be labelled racists, dickheads or dinosaurs.’

And the wider issues at stake? Australian journalist Peta Credlin said: ‘Albanese has been trying to exploit the goodwill that just about every Australian has towards Aboriginal people, and our commendable instinct to want to end Indigenous disadvantage, to drive a profound change to our system of government, based on the notion that the settlement of Australia was fundamentally unjust. That’s why it needs to fail, and why the bigger its failure the better in the long run.’

Albanese had once spoken about a referendum on Australia ditching the monarchy and becoming a republic. I suspect we won’t hear much more about that plan now. The Voice campaign was fought along the Remain playbook, and it lost for the same reason. But the wider theme – of Australia rejecting identity politics as a divisive and inimical to social cohesion – is one that’s likely to resonate beyond Australia’s borders.

Comments