For a politician to draw attention to his own deficiencies is a desperate attempt to curry favour with the electorate that has been tried before with dismal consequences. The most famous case is that of the former Tory leader Iain Duncan Smith who, at his 2002 party conference, addressed the problem of his dullness as a political performer by saying that no one should ‘underestimate the determination of a quiet man’. One result was that Labour backbenchers would raise a finger to their lips and say ‘shush’ whenever this croaky-voiced man was speaking in the House of Commons. He tried to sound tougher at the next year’s Conservative conference by saying that ‘the quiet man is here to stay, and he’s turning up the volume’; but this made him look even sillier and only hastened his overthrow as party chief.

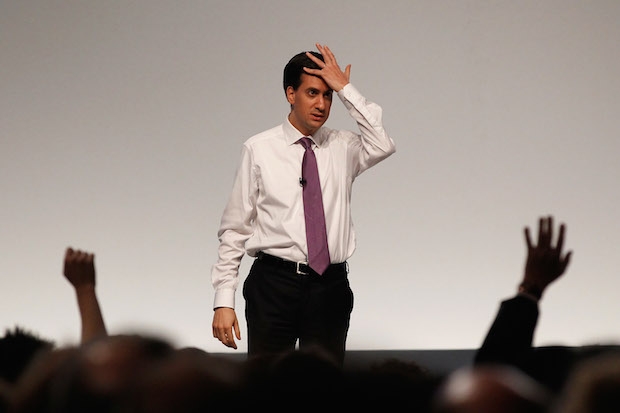

Ed Miliband did something similar when he confronted his wretched personal ratings in the opinion polls by admitting to looking weird and being useless at photo opportunities. But he tried to make these deficiencies seem like virtues by suggesting that he was bravely standing up against a ‘showbiz’ culture that was creating disillusionment with politics today. ‘I am not from central casting,’ he said. ‘You can find people who are more square-jawed, more chiselled, look less like Wallace. You could probably even find people who look better eating a bacon sandwich. If you want the politician from central casting, it’s not me, it’s the other guy.’ The other guy, David Cameron, was a master of presentation, of the photo-op; he, on the other hand, was a man of principle, one who cared about people, for whom good policies were all that mattered. It was inevitable, therefore, that some should ask why he had hired a voice coach, a ‘posture’ adviser, an ‘empathy’ expert, and an American spin doctor.

Self-deprecation can work. Ronald Reagan was a master of it. But when he said, ‘It’s true hard work never killed anybody, but I figure, why take the chance?’, he wasn’t drawing attention to a perceived defect but re-

enforcing a much-loved popular image. It wasn’t actually true that he was idle — his diaries show that he worked very hard — but Americans warmed to the idea of a relaxed, easygoing man in the White House; it made them feel comfortable and safe. Reagan may in some small respects have been a bit of a fraud, but he was basically authentic; and authenticity is surely the quality that a successful leader must have. But as Ed Miliband will discover, you can’t spin yourself into authenticity.

You can be authentic and still unpopular, of course. Edward Heath was an example. But you can’t earn respect without it. Margaret Thatcher was loathed by many people, but the undoubted strength of her convictions brought her victory in one election after another. As her former PR guru Lord Bell wrote this week in the Daily Mail, ‘It is one of the great myths of her rise to the leadership that she was an artificial construct manufactured by PR figures like myself and Gordon Reece…The idea that someone as tough and self-confident as Mrs Thatcher could be a puppet in the hands of advisers is just nonsensical.’ Boris Johnson could hardly be a more different figure, but his own brand of authenticity — that of a person who is true to himself and doesn’t even hide his flaws — is one reason for his enormous popularity.

This is not to say that presentation doesn’t count; think of Tony Blair. And David Cameron, while failing to convince people of his genuineness, has achieved much with his presentational skills. The old man who used to mow my lawn, the wise and cultivated Patrick Parkes, who sadly died this week, had been a lifelong Labour voter; but he told me he was pleased when Cameron became prime minister because he looked the sort of person who could convincingly represent Britain abroad. This is something else that people mind about, and it doesn’t work to Ed Miliband’s advantage.

There may, however, be more to Miliband than meets the eye. According to Ann Treneman, the political sketchwriter of the Times, who claims to have watched him ‘more than most’, he is not merely ‘detail-driven and an obsessive, an ideologue who believes he can take Britain into a new world with his policies’ (which are indeed very left-wing); he is a ‘baseball fanatic’ who is so infatuated with this American sport that he ‘is on his way to founding a religion about baseball’. This may well be completely authentic, though I don’t see how it will help him very much over here.

This is a preview of Alexander Chancellor’s ‘Long life’ column from this week’s Spectator. To receive three months of magazine for just £12 click here.

Comments