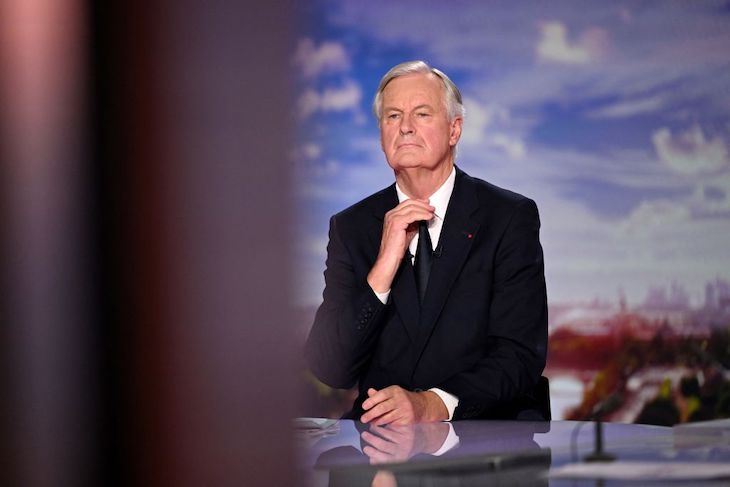

France’s 73-year-old prime minister, Michel Barnier, underwent surgery last weekend for a lesion on his upper neck. According to the government spokeswoman yesterday, the operation ‘went well’ and the PM is back at work after two to three days’ rest. French media have been characteristically tight-lipped about the health of France’s second in command and the Fifth Republic’s oldest prime minister.

French media have been characteristically tight-lipped about the health of France’s second in command

Le Monde – sometimes thought of as an unofficial organ of the state – merely trotted out the official communiqué; Le Figaro added that the operation was considered benign and that test results will be known in coming weeks. It is the first time in 40 years, as far as we know, that a serving French prime minister has been operated on, although presidents Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy were both hospitalised in 2005 and 2009 with minimal media fuss. Even with today’s prurient social networks, France’s mainstream media continue to display restraint about their leaders’ health.

It used to be said that when the English made polite conversation it was about the weather, the French about their health. But when it comes to their leaders’ health they are remarkably discreet, claiming respect for their private lives. France’s leaders are not required to make health conditions public and some have refused to disclose major illnesses while in office. Thus the terminal illnesses of presidents Georges Pompidou and François Mitterrand, though diagnosed while in office, were prudently kept under the carpet by the media, despite the French president’s finger being on the nuclear button.

For all France’s referencing of the word ‘Republic’ – usage of which over the last decade has all but replaced the word ‘France’ in the mouths of politicians – she is still unable to shake off more than a millennium’s worth of monarchy. The Fifth Republic, often dubbed the ‘republican monarchy’, confers on its president quasi-regal powers. Its founder, General de Gaulle, in his youth was sympathetic to monarchist authors; documents have revealed that he even sounded out the Orleanist branch of the French monarchy as to a possible restoration in the 1960s, as General Franco was later to do with the Spanish Bourbons. The Elysée Palace’s present occupant is regularly referred to as King Emmanuel (which he probably enjoys). His public address on the death of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022 graciously recognised her as having also been France’s queen. Two weeks ago during King Charles’s royal tour of Australia a visitor to France might have wondered whose monarch he was, given French media’s coverage of the trip.

Does the answer as to why the French are so discreet about the health of their political leaders lie in a deep-seated monarchical atavism? In 1957, a major work of medieval political theology appeared, The King’s Two Bodies. Based on study of the Tudor and French monarchies, its author the German-American Ernst Kantorowicz, argued that within a monarchical state the ruler was possessed of two bodies; the physical body and the body of the whole polity. Thus the king’s mortal body, with all the infirmities that might weaken it, is inconsequential in comparison to the body that cannot be seen representing the public weal. Hence the phrase: ‘The King is dead; long live the King’.

A prurient Anglo-Saxon media is unrelenting in its search to uncover the slightest infirmity in their political leaders, whereas the French are ‘more royalist than the king’ in not inquiring as to the defects, infirmities and peccadilloes of their political leaders.

In the light of Barnier’s surgery, a recent French radio panel discussion touched on the question as to whether French journalists should be more inquisitive about their leaders’ health. The subject of the King’s ‘two bodies’ was cited as to why the media should not pry into the state of the mortal body; the function is important, not the man.

Yet precisely because France is no longer a formal monarchy, the line of political succession is unclear. It is particularly so in the case of Michel Barnier. He is the perfect prime minister to sort out the country given his age and absence of ambition for 2027. France’s present contorted and tense state, the absence of any hope of a parliamentary majority for at least a year, and the impediment of major political figures refusing to succeed him for fear of spoiling their chances for the presidency, makes this prime ministership crucial. Barnier’s ‘body natural’, his corporeal being, his health, is vital for the salvation of France’s present-day body politic.

Comments