Does George Osborne need to adopt a Plan B? This will be the topic for a Spectator debate a week on Monday. But the argument is pretty clear to everyone with even a passing interest in the trials of George Osborne. Let’s look at the story so far.

His Plan A – accelerated fiscal consolidation – was based on two key premises:

- there was no alternative to cutting the deficit much more sharply than previously planned, because otherwise the markets would panic and long-term interest rates would rise sharply. As one Treasury Minister put it:

‘Britain’s AAA credit rating was under threat…George Osborne had no choice but to come up with a comprehensive deficit reduction plan—not to merely halve the deficit over four years, but eliminate it.’

- that fiscal consolidation would have only have a small impact on growth, or indeed might even be beneficial. Matthew Hancock, George Osborne’s former Chief of Staff (now a Minister at the Department for Business) discovered that ‘research into dozens of past fiscal tightenings shows that, more often than not, growth doesn’t fall but accelerates’.

The past two years have tested both assumptions, and found them failing. The deficit is now forecast to be if anything larger than before ‘Plan A’ was announced; yet, as deficit forecasts have risen. Rather than panic, markets have responded by dropping long term interest rates not just here, but in the US, Japan and indeed in every industrialised country that has an independent monetary policy and borrows in its own currency (ie, those not in the eurozone).

And should George Osborne take a bow, saying that these low rates are a reward for his cuts? Both economic theory and the empirical evidence demonstrate beyond serious doubt that the current low level of interest rates is the result of weak growth, both here and internationally.

Meanwhile, as the IMF has belatedly recognised, it now seems clear that the negative impact of ‘Plan A’ on growth has been significantly greater than expected, although matters have also been exacerbated by even more damaging policy mistakes in the eurozone, as well as high commodity prices.

What is the government’s response to this critique? At the moment, it appears to be to argue that the success of Plan A is demonstrated by the fact that ‘we’ve cut the deficit by a quarter‘. Leaving aside that cutting the deficit by a quarter by now was precisely what was planned before Plan A was announced in the first place; and leaving aside too that so far this year the deficit has actually increased sharply, how has this cut been achieved? Mostly, by cutting capital spending – public investment, as I explain here.

So what should we do? The main short-term problem, as Vince Cable argues, is a lack of demand. And this is easily remedied. The government can borrow money for essentially nothing (the yield on long-term index-linked gilts is close to zero).

It’s not as if we can’t think of anything to spend money on. The UK suffers from both creaking infrastructure and a chronic lack of housing supply, especially of affordable housing. In these circumstances, both common sense and basic macroeconomics argue that it is the role of government to channel those private sector savings into demand and investment, by borrowing more if need be. In addition, a temporary, but large, cut in National Insurance Contributions for both employers and low-paid employees would boost labour and consumer demand at the same time as improving work incentives. Broader and more comprehensive measure to tackle youth unemployment would also help.

So in the short term, there is plenty that can be done to help the UK economy. The main thing holding back growth in the UK is bad policy, here and of course in the eurozone. Over the longer term sustainable growth will require a whole host of policies: planning reform, increased aviation capacity, better quality education for disadvantaged children, better childcare provision, clearer pathways from school to work for those who don’t go on to higher education.

On all of these, we know what the problems are, but successive governments have failed to address them. One policy area that currently works very well, however, is the labour market, which has performed extraordinarily well of late. Three decades of successful reform have given the UK a flexible and generally well-functioning labour market, suggesting that there is little to gain from further deregulation. Spain and Italy need radical labour market reform; but we don’t.

There is however one area where deregulation is urgently needed, and that is immigration. The government has introduced a set of new burdensome and bureaucratic rules and regulations, including a quota on skilled migrants, that are designed expressly to make it more difficult for businesses to employ the workers they want. By the government’s own estimates, this will reduce growth and make us poorer. But another consequence has been to take a thriving, dynamic and high value-added export industry – further and higher education – and stop it from selling its product to foreigners.

As long as the UK policy debate focuses on immigration as a threat to be minimised, rather than as a potential driver of growth and innovation, then the UK will not be ‘open for business’.

The UK economy has many underlying strengths. Since 1995, GDP per capita has grown faster than in Germany, France, Japan or the US. This reflects improvements in the UK labour market, a more skilled workforce and a more competitive economy. There is, of course, plenty to worry about. We are still stuck in the longest period of stagnation in recorded economic history, thanks to damaging and unnecessary policy failures, both here and globally. But things could and should be better. If only policymakers would act.

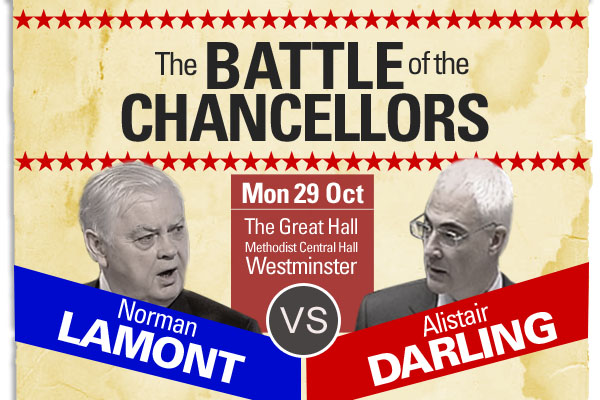

Jonathan Portes is director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and former chief economist at the Cabinet Office. To book your seats for the Alistair Darling vs Norman Lamont debate, a week on Monday, click here. Ryan Bourne from the CPS will respond tomorrow.

Comments