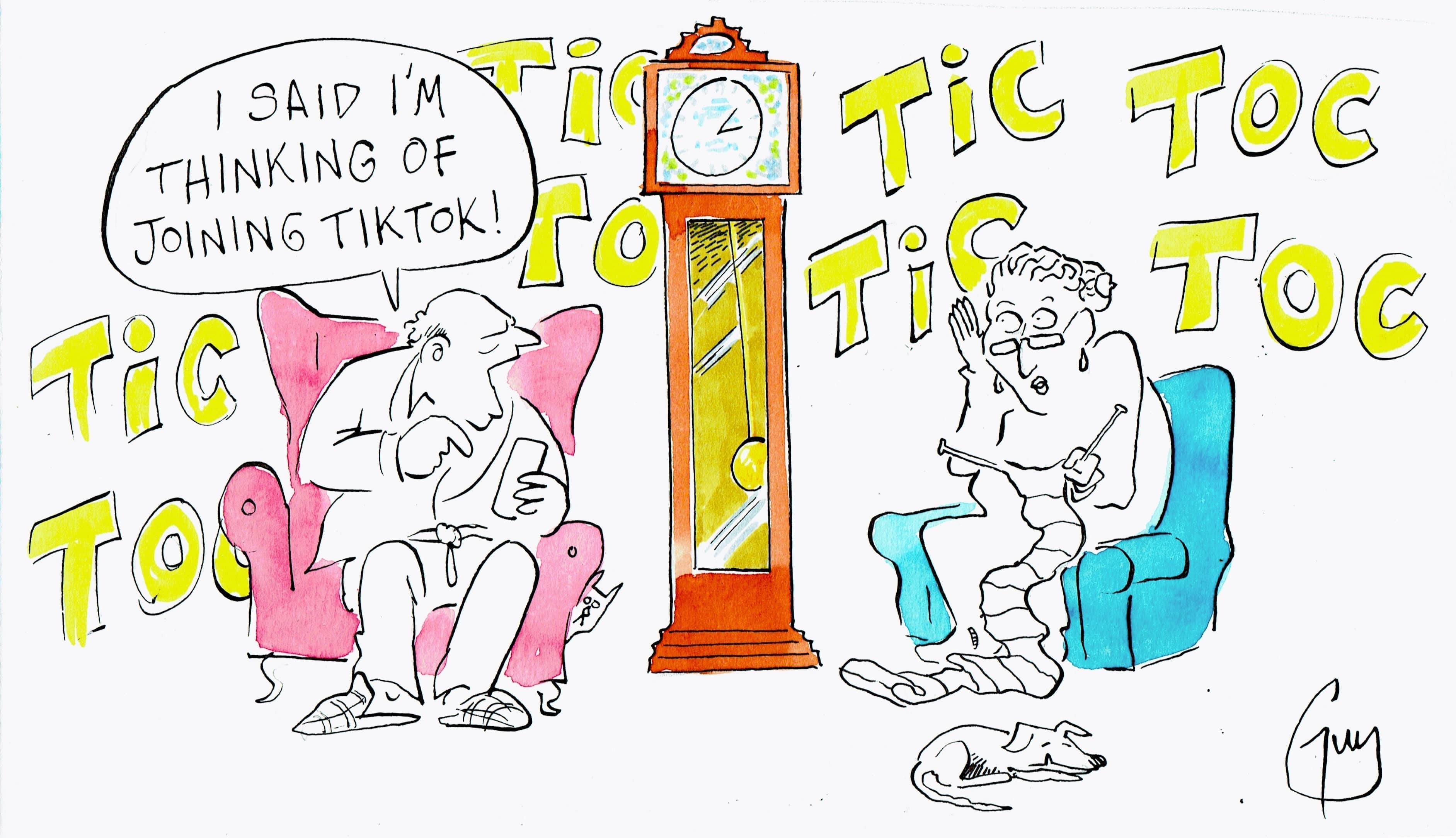

Just over a week ago – and to some derision from both friends and followers – I proudly announced I had started a TikTok account. The criticisms were wide and varied. Buzz words included ‘Sad’, ‘Tragic’ and accusations about an interest in young people that wouldn’t be decent to print here, but that Boris would probably shout across the despatch box.

I’m going to go out on a limb and speculate that your average Spectator reader isn’t the absolute target market for a site like TikTok. But Michael Gove probably wasn’t the go-to punter for a hard house night in Aberdeen, so you never know.

My reasons for joining TikTok were fairly simple. I’m aware – and grateful – that the appeal I have is predominantly to men of a certain vintage. Men of a certain worldview. Men who like me can still look like an electrician even if they’re wearing a dinner jacket. As a comic I appreciate anyone who parts with their hard earned cash to see me on tour. Equally, on a pragmatic level, it makes sense to try and widen your appeal to young people too, people who don’t need to take into account wear and tear on the knees when sitting down for an hour of comedy.

I was aware that TikTok ‘skewed young’ in the same way Viking River Cruises ‘skew retired’. Throw in the fact that TikTok is also a bit of a wild west when it comes to copyright it all seemed like a good way to get some short clips out there and earn some respect from teenage relatives who seem to regard comedy panels shows in the same way I viewed The Generation Game.

TikTok surmises that, without curation, all we’d watch is videos of ourselves staring at ourselves.

I’m glad I did it – not just for promotional reasons, but for the insight it’s given me into a side of both young people and a Britain I knew nothing about. It turns out that as things change they also stay the same. Teenage girls still do choreographed dance routines. Either that or lip-synching somewhat narcissistically to Billie Eilish. Thankfully the algorithm quickly learns this isn’t your thing, but it worried me a little. Primarily because in my childhood the girls on the estate would often spend their Saturday afternoons working up dance routines to Janet Jackson. God knows the effect on their psyche if those dances had been available to a global audience of a billion people.

Other videos are simply chaotic and funny. On Twitter, rewards are given for pithy humour and clear thinking. On TikTok credit goes to someone nodding their head in time with their Cockapoo. You might think that cat videos were already a popular phenomenon on Youtube, but this site takes that genre and runs with it.

I’ve often criticised the liberal control of media entertainment. However, if YouTube taught us that, left to our own devices, we’d just watch cat videos, TikTok reveals that, without curation, all we’d watch is videos of ourselves staring at ourselves.

One interesting element of the humour is how much of it relies on exaggeration. Kids deploy supreme hyperbole in their reactions, whether it’s to a trailer for a new film or a single message on a Whatsapp group which has sent them into a tailspin. This is an extension of GIF culture, which I’ve always found fundamentally dishonest when used by Brits. You get one of your most reserved mates posting ‘Me reacting to Boris like…’ and they’ll have a video of some fabulous drag queen vibrating with rage until their weave falls off. If GIFs were truthful for British people 90 per cent would be an image of someone shrugging their shoulders whilst desperately trying to conceal deep levels of judgement and contempt.

In fairness to the kids, however, maybe taking the small moments and making them big is a natural instinct for people a generation who became young adults during lockdowns. What choice did they have when the most exciting part of the day was fist-fighting their siblings over who had the privilege of going to the Co-op to get milk.

A less savoury element is the comments section. Twitter is given a hard time for being ‘toxic’ and a ‘cesspit’. But TikTok is like travelling back in time to the most rancorous part of the Brexit wars and ordering everyone a round of shots. Not only are insults flying, they’re coming from the kind of lads who ask other people to get cider for them.I’ve had to stop myself returning fire replying when I realised the kid giving me a history lecture hadn’t started GCSE history.

Away from the judgemental eyes of Journos and public figures, where ordinary people can trend for off colour comments, the rows on TikTok can rumble on for days.

Thankfully, some of it can be charmingly innocent. One lad replied to a clip of mine with ‘You are a good comedian….NOT’. I imagine he was well happy with that. I don’t know if he actually got it from Wayne’s World, but if he did it was probably in one of 20,000 digestible 15 second clips.

In the same way Facebook existed for years before lawmakers became concerned about its darker corners, I suspect the blind spots on TikTok will exist for some time before they face public scrutiny. And let’s be honest, the fact that a 45-year old gammon like me now has an account is probably a sign that young people may migrate further still in the not too distant future.

For now, I’m glad I set up an account. One of the things I liked about being a teacher before I became a comedian was that I kept a foot in the mind and world of the young. You knew the new words and trends and I’m reassured to see that some things really don’t change. Young girls like practising dances. Good looking people like staring at themselves. Young boys still think ‘nukeing’ things is a genuine diplomatic option. So yes, on balance I think TikTok is great and will continue to do so – right up until my son wants to open an account.

Comments