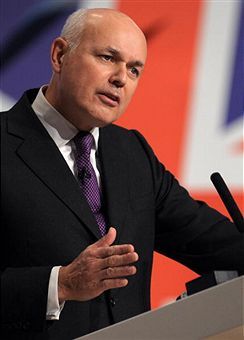

Before everyone gets too excited, Iain Duncan Smith is not saying in his speech today that immigration is a bad thing in itself. But he is saying

that it has consequences, some of which impinge on native Brits. Many of these consequences are, as it happens, writ in the official statistics. As IDS highlights – and as Coffee House has

detailed before – a good number of the jobs that sprang up

during the New Labour years were accounted for by immigration; and there are signs that the process is continuing still. This is one of the reasons

why the number of jobs in the economy can increase, while the dole queues barely shorten. Workers are imported, rather than nurtured.

Before everyone gets too excited, Iain Duncan Smith is not saying in his speech today that immigration is a bad thing in itself. But he is saying

that it has consequences, some of which impinge on native Brits. Many of these consequences are, as it happens, writ in the official statistics. As IDS highlights – and as Coffee House has

detailed before – a good number of the jobs that sprang up

during the New Labour years were accounted for by immigration; and there are signs that the process is continuing still. This is one of the reasons

why the number of jobs in the economy can increase, while the dole queues barely shorten. Workers are imported, rather than nurtured.

This isn’t the fault of the immigrants themselves: they are selling their skills as well they might, and to willing buyers too. But IDS’s suggestion that immigration needs to be “controlled” nonetheless is nothing new. It was, for instance, the policy of the last government to prioritise certain skilled immigrants over others. One rationale they gave for this was to “maintain the highest possible levels of British graduate employment.” Even the Lib Dems, who will no doubt be wary of IDS’s speech today, called for measures to “manage migration” in their manifesto, including a “regional points-based system to ensure that migrants can work only where they are needed.”

Which leaves IDS’s exhoration that British employers give British workers a chance – and “not just fall back on labour from abroad” – as perhaps the most eyecathing passage of his speech. British employers might reply, in turn, that they do give British workers a chance, but they are often found lacking in comparison to their foreign counterparts. As The Spectator’s recent supplement on “Britain’s Skills Crisis” emphasised, this country has skills gaps among its workers, and Polish builders, Bangladeshi curry chefs, whatever, are more than able to occupy the breach. “Make Brits more employable,” the employers will say, “if you want us to employ them.”

But, thankfully, this is exactly what IDS plans to do. His Universal Credit will make the path to work clearer and more accessible. And Chris Grayling’s Work Programme aims to train claimants in those sorts of skills that will make them more employable. If they pull it off – if they create British workers for British jobs, as it were – then employers will be compelled to give Brits not just a chance, but a pay packet as well. If they fail, then the coalition faces one of its starkest nightmares: a recovery that amounts to a jobless one for some of the most downtrodden parts of the country.

Comments