Growth plans are a high growth industry — with every day bringing yet another set

of ideas, from one quarter or another, for how the government can fix the economy. And one suggestion pops up quite frequently in all these plans: bring forward spending on infrastructure. This is

often presented as a simple thing to do, with few (if any) downsides. But how realistic is this?

Growth plans are a high growth industry — with every day bringing yet another set

of ideas, from one quarter or another, for how the government can fix the economy. And one suggestion pops up quite frequently in all these plans: bring forward spending on infrastructure. This is

often presented as a simple thing to do, with few (if any) downsides. But how realistic is this?

We know that infrastructure is important for growth. Economic texts generally suggest that the ‘multiplier effect’ (when government spending leads to more private spending later on)

from is higher for infrastructure spending than for spending in other areas, such as health and welfare. We also know that the UK’s infrastructure needs to improve. It performs poorly in

international surveys, and there are problems with congestion on roads and airport capacity in London.

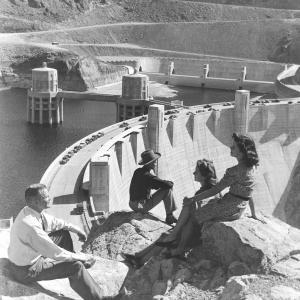

All of which suggests that the government should spend more money to get unemployed people working on infrastructure projects. This was the approach taken in the US, in the early 1930s, with the

construction of the Hoover Dam — which employed thousands of workers, including large numbers of previously unemployed men. But there are some serious problems with relying on this approach

for the here and the now. Here are three of the main ones:

i) The short term economic benefit of bringing forward infrastructure spending should not be exaggerated. Prioritising infrastructure spending is, for instance, unlikely to have

much of an impact on unemployment. The days of building damns with thousands of unemployed workers with picks and shovels are long gone. Modern infrastructure projects are capital intensive

projects and employ, in most cases, very skilled labour. Businesses are already struggling to find the requisite skilled labour, with a recent CIPD survey showing that 23 per cent of firms have

engineering vacancies that are hard to fill.

ii) Bringing forward spending increases the chance of building the wrong thing. Not all infrastructure projects are good for growth. The focus must be on building the right

infrastructure, not just building infrastructure. (Indeed, the focus should also not just be on ‘building,’ but also on improving how projects are funded and regulated, and freeing

their operation.) Athens is a good example of how it can all go wrong, with Olympic venues now vacant and fenced off. There are many other examples of white elephants, including bridges to nowhere

(such as the Hamada Marine Bridge in Japan) and unused airports (such as Castellón Airport in Spain). Infrastructure projects are financially large commitments and very difficult to reverse.

Adopting a ‘build it and they will come’ attitude is asking for waste.

iii) Increasing borrowing to fund infrastructure risks stretching the Government’s fiscal credibility to breaking point. On current trends, the coalition is likely to miss its target

of eliminating the structural deficit before the general election. Markets will be looking for reassurance that this is because of a downturn in world growth (especially in the eurozone), and not

because of a weakened commitment to deficit reduction.

It could be argued that under Gordon Brown’s ‘Golden Rule’ spending on infrastructure (capital spending) should be treated differently from other spending. Yet, after Greece, the

markets are likely to have much lower tolerance for national accounts that are engineered to mask spending and debt. The government would be quizzed about where the money for extra infrastructure

spending is coming from, as well as about the difference between its reported debt ratios and the true level of public debt. Any gains in credibility from establishing the Office for Budget

Responsibility could be lost.

In sum, when it comes to infrastructure, the coalition must resist the temptation of quick fixes. Ministers are right to want to improve the UK’s infrastructure, but rushing projects forward

risks wasting money and damaging the coalition’s fiscal credibility. Weak growth makes it more, not less, important to ensure that decisions are based on clear cost-benefit grounds, and not

on political whim.

Patrick Nolan is chief economist at Reform

Comments