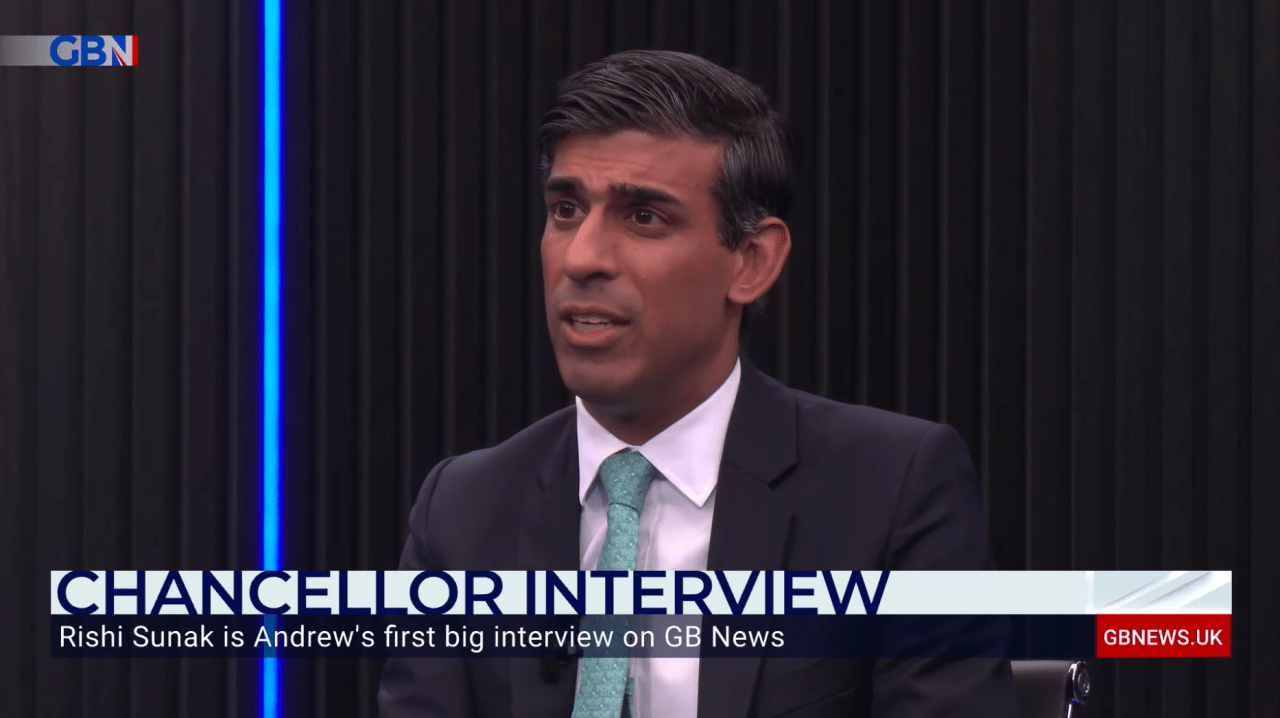

Chancellor Rishi Sunak agreed to sit down with Andrew Neil on GB News last night for what turned out to be a fairly brutal grilling. The Chancellor floundered under interrogation on the pensions triple-lock, the cost of climate-friendly policies and the Tories’ big-government instincts. However, one of the more uncomfortable moments came when Neil pressed him on the future of the £20 weekly Universal Credit uplift. The benefit supplement, which also applies to the basic element in Working Tax Credit, was introduced at the start of the pandemic because the government acknowledged that the coming recession would inflict particular hardship on those already on the lowest incomes.

Announcing the 12-month increase last March, the Chancellor said: ‘I cannot promise you that no one will face hardship in the weeks ahead, so we will also act to protect you if the worst happens.’ That meant, he said, taking measures ‘to strengthen the safety net’, citing the uplift by way of example.

When this March rolled around and we remained in lockdown, Sunak extended the uplift for a further six months, meaning it is due to expire at the end of September. Labour and various civil society groups are pressing for the extra £20 to be made permanent but there are no signs as yet that Number 11 is budging. It should take the Andrew Neil interview as a dress rehearsal for the next three months, when the Chancellor will come under intense pressure either to extend again or simply accept that returning people to the welfare status quo ante is a non-starter and make the uplift permanent.

The latter option may be the prudent thing to do politically but it is also, happily, good policy. If the government pulls away this economic ladder, it will drop millions of families into a worse financial position near the end of the year — i.e. in the run-up to Christmas. Among these families are the very D and E voters the Tories hope to make their own. (Whether that is a correct reading of electoral trends is another matter.) The £20 uplift is also a harder benefit to argue against because a) it has ‘£20’ in its name and b) the Chancellor himself described it as strengthening the safety net, implying that taking it away again would be weakening said net.

This is not a welfare policy like the housing benefit cap, where Labour’s objection to cuts didn’t necessarily chime with all of the party’s voters outside London. The uplift doesn’t play out as welfare recipients getting ‘special’ treatment or taxpayers’ largesse. It plays out in the context of the early days of a titanic effort at economic recovery. Even if the economy bounces back once the shackles have been lifted, the benefits are unlikely to be felt before the end of the third quarter and even then there is no knowing when they will reach those reliant on the uplift and — at least as crucially — those not currently on Universal Credit but whose employment situation is precarious enough to make them fear they soon might be. Bluntly, if the economy roars back to life, the Chancellor can get away with scrapping the uplift but if the reawakening is more gradual, it may be politically difficult to snatch it away suddenly.

At the start of the year, when it wasn’t yet clear whether Sunak would extend the benefit, the Chancellor was reportedly considering scrapping it while giving Universal Credit and Working Tax Credit recipients a one-off lump sum payment of £500, equivalent to six months of uplift money. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimated this would cost £3bn, or half of the bill for a full-year extension, and suggested the Exchequer could alternatively spend the same amount on a ‘tapering off’ policy that reduced the uplift over the course of the year and allowed families to adjust gradually to less cash rather than grabbing the money away in one go.

Undoubtedly, keeping the uplift for the long-term would be costly — £6.4bn a year, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. But the policy case is as strong as the financial outlay is daunting. The JRF says withdrawing the supplement would mean plunging 500,000, including 200,000 children, into poverty, with single-parent families suffering the most. Six-in-ten single-parent families would take a hit to the pocketbook. As the Resolution Foundation has noted, the UK had one of the lowest income replacement rates for unemployment benefit in the OECD before the pandemic hit, with welfare payments making up less than half of previous earnings at 48 per cent of the average wage, compared to an OECD average of two-thirds. Only Greece and Australia’s safety nets were less generous. The Foundation contends: ‘The welfare safety net we had in the run-in to the Covid-19 crisis was insufficient for families, contributing to the years of poor pre-pandemic income growth for low-income households’.

Even with the additional support, low-income families have struggled. Analysis by the think tank Bright Blue shows that almost half of Universal Credit claimants reported being behind on household bills last November, while a quarter said they were unable to keep up with rent or mortgage costs. If Number 11 is determined that the uplift must not continue beyond November, a lump-sum payment would go some way to softening the blow, but the Treasury should consider the merits of continuation. The Chancellor might balk at a permanent uplift but it is actually the middle-ground option between another bout of Osborne-style welfare brutalism and the more substantial increases in benefit spending required to bring Britain’s safety net in line with similar advanced economies. It would require tax increases to fund it, and so the Tories will have to decide if, as well as being a (relatively) big-spending party, they are now also a party willing to countenance asking the voters to pay more in taxes. However they decide to answer the question, a Tory party that believes in levelling up should recognise strengthening the social safety net as a key component of that project.

Comments