The Chinese Communist party (CCP) is spooked by Halloween. In Shanghai, police have rounded up people gathering in costumes that included a Donald Trump with bandaged right ear, Spiderman, Deadpool and Batman. A man dressed as Buddha was also shown being escorted away in videos posted on Chinese social media, but quickly deleted by online censors. The aim seems to be to prevent a repeat of last year’s celebrations, when revellers used the occasion to take a tongue-in-cheek poke at the CCP, and costumes included a surveillance camera and hazmat suits (a swipe at Covid lockdowns).

It has at times been like a game of cat and mouse

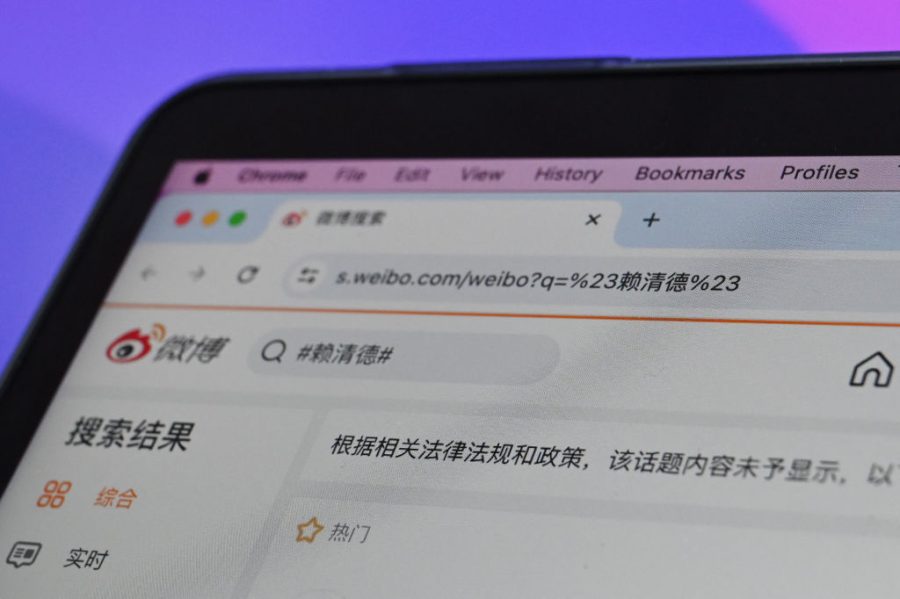

The online censors have the most difficult task perhaps, since Halloween – which is surprisingly popular in China – is fertile territory for memes, puns and homophones. It will provide a test for a new campaign by the government to close what has been one of the last remaining ways for people to discuss sensitive subjects and poke fun at an increasingly humourless and paranoid CCP. The ‘clear and bright’ campaign claims to be targeting ‘irregular and uncivilised’ online language, according to the Cyber Administration of China.

‘For some time, various internet jargons and memes have appeared frequently, leaving people more and more confused,’ thundered an editorial in the CCP’s People’s Daily. ‘They also form a hidden erosion on the daily communication and ideological values of minors, which can easily lead to adverse consequences.’ ‘Obviously ambiguous’ words required ‘rectification’, the paper said.

Often the word play is quite subtle, such as the use of ‘your country’ instead of the CCP’s preferred ‘my country’ as a way of criticising CCP rule. When Joe Biden announced he would not stand for re-election, censors targeted posts commending elderly or incapable leaders for retiring early, fearing it was veiled criticism of Xi Jinping – which, of course, it was. Historical allusions are another popular technique for side-stepping censorship. Last year, the censors erased all reference to Chongzhen: The Diligent Emperor of a Fallen Dynasty, which attributed the fall of that dynasty to the emperor’s ineptitude and paranoia. They scrubbed all screenshots and comments, including, ‘Bad moves one after another, the more diligent [Chongzhen was], the more the kingdom died.’

Perhaps the most famous visual pun was Winne the Pooh, images of which were used to reference Xi, with whom the rotund bear shares a remarkable likeness. Poor old Pooh Bear has now been well and truly outlawed from the Chinese internet. When censors banned the use of the #MeToo hashtag on Chinese social media, users began posting images of a bowl of rice (pronounced mí in mandarin) and a bunny rabbit (tù). In discussing protests in Henan province over bank fraud, netizens (as members of internet communities are often called in China), used the characters for hélán, which means the Netherlands, but sounds an awful lot like Henan to sidestep the restrictions. Another pun, zhèngfǔ, sounds a lot like the mandarin word for government, but means totally rotten. There was even a way of describing censorship, which originated with the word for river crab, which sounds almost the same as the word for harmony – and if something has been harmonised, it has been censored.

It has at times been like a game of cat and mouse. The 4 June anniversary of the Tiananmen square massacre is always a busy time for censors and those looking for ways to sidestep the controls. One imaginative netizen doctored the famous photograph of a protester facing down tanks, replacing the tanks with a row of ducks. It came soon after a Dutch artist named Florentijn Hofman created a 53 feet tall sculpture of a yellow rubber duck and took it on tour to China, floating it on rivers and lakes in a number of cities. That made rubber ducks immensely popular, but didn’t stop the CCP from banning any further reference to them on the Chinese internet.

China’s Great Firewall, as the system of internet censorship is referred to, is the world’s most extensive and technologically sophisticated. It has had several upgrades since it first emerged as a way of blocking websites and an evolving list of keywords deemed dangerous by the CCP. These days it can spot images and is complemented by an army of internet police, who do not just censor but join conversations in order to blunt or steer them. The Great Firewall is also integrated with other elements of the surveillance state, including cameras with facial or gait recognition and location and other behavioural data from mobile phones and social media aimed at imposing the CCP’s claustrophobic control.

The CCP is deploying artificial intelligence (or at least machine learning) in its censorship and surveillance efforts. Still, its bid to crack down on wordplay and memes may be a challenge. As Ai Weiwei, the exiled Chinese artist once told me, ‘The Communist party is probably the funniest thing that exists – but it doesn’t have a sense of humour.’ In the battle with China’s brave netizens that is a handicap for the party and a vital asset for those battling to maintain a semblance of free expression.

Comments