Much has been made of the decision to place the Metropolitan Police in what is often referred to as special measures, where it joins five other forces from England and Wales. The many ways in which the Met has fallen short have also been amply aired, from the murder of Sarah Everard by a serving officer to the botched investigation of serial killer Stephen Port, to the racist and sexist mindset laid bare at some London police stations. Many crime rates in the capital have been rising sharply, as – naturally – has public dissatisfaction.

Nor should the blame game that has broken out between the Home Office and the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, come as much of a surprise. With the search for a new Commissioner to replace Dame Cressida Dick now in its final stages, this is becoming an argument about how to remedy the Met’s very evident failings and what its priorities should be in the immediate future.

The antagonism is nonetheless striking, with the policing minister accusing Khan of being ‘asleep at the wheel’ and Khan’s retort that he had long called for changes, only to be blocked by Patel herself and the Prime Minister. Such recriminations hardly bode well for administrative harmony, once a new Commissioner is in place.

But this latest quarrel should also suggest something else: that much of the very public agonising about what is required in a new Commissioner, including a determination to introduce radical reform, may be barking up the wrong tree. Is it really, or only, about the character of the new appointee? Might it not be at least as much about structures and responsibility? Because London has been here before, hasn’t it? And not so long ago. In the past decade, relations between the then Home Secretary Theresa May and the then-mayor of London – none other than Boris Johnson – were at times as tempestuous as they currently appear to be between Priti Patel and Sadiq Khan.

It is high time that England and Wales, if not the whole of the UK, had a genuinely national police force

They got off to an acrimonious start, over – guess what – the appointment of a new Commissioner, with Johnson unhappy with the original list and wanting the right of veto. The technical position is that the Commissioner is appointed by the Queen on the recommendation of the Home Secretary, who is supposed to have ‘regard’ for the mayor’s opinion. But it is not hard to see in this formula a recipe for strife. Four years later, in 2015, Home Office-City Hall relations became, if anything, worse, over Johnson’s pre-emptive purchase of water cannon for use in the event of a re-run of the 2011 London riots. In the end, the mayor had to concede defeat, even though he had the support of the then Commissioner, Bernard Hogan-Howe. National policy, as decided by the government, apparently overrode what the mayor judged necessary for London.

Now that it is his Home Secretary facing off against his successor as mayor, the irony can hardly be lost on Johnson. Even if the details of the disputes are different, the essence is the same: who is ultimately responsible for the force that polices London? Where does the buck stop; who has the final say? It is never good for the answers to such questions to be blurred in any power structure, but particularly not when the subject is policing.

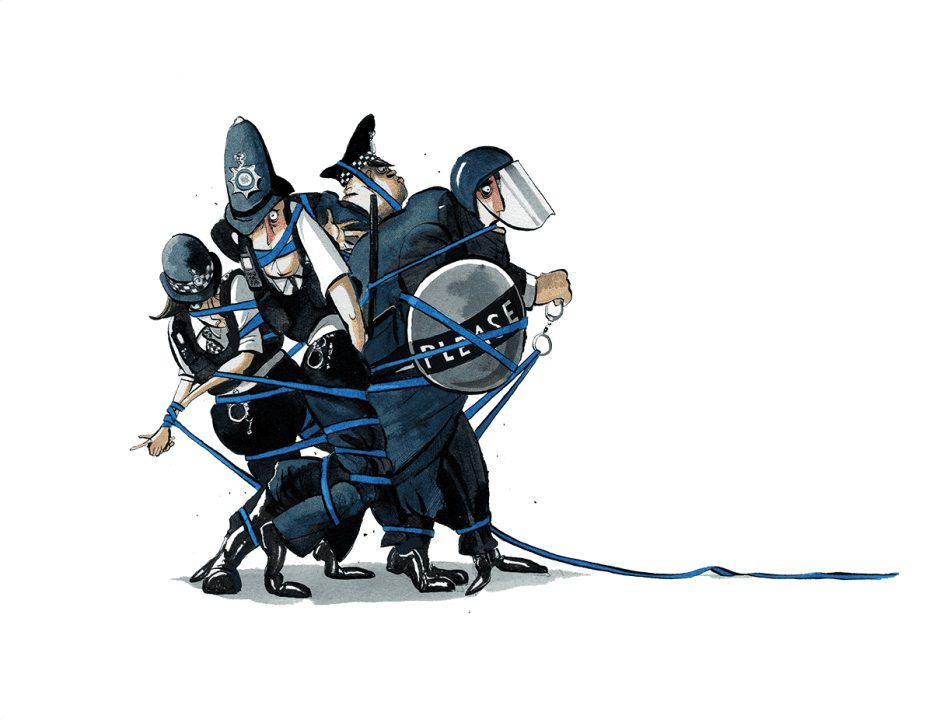

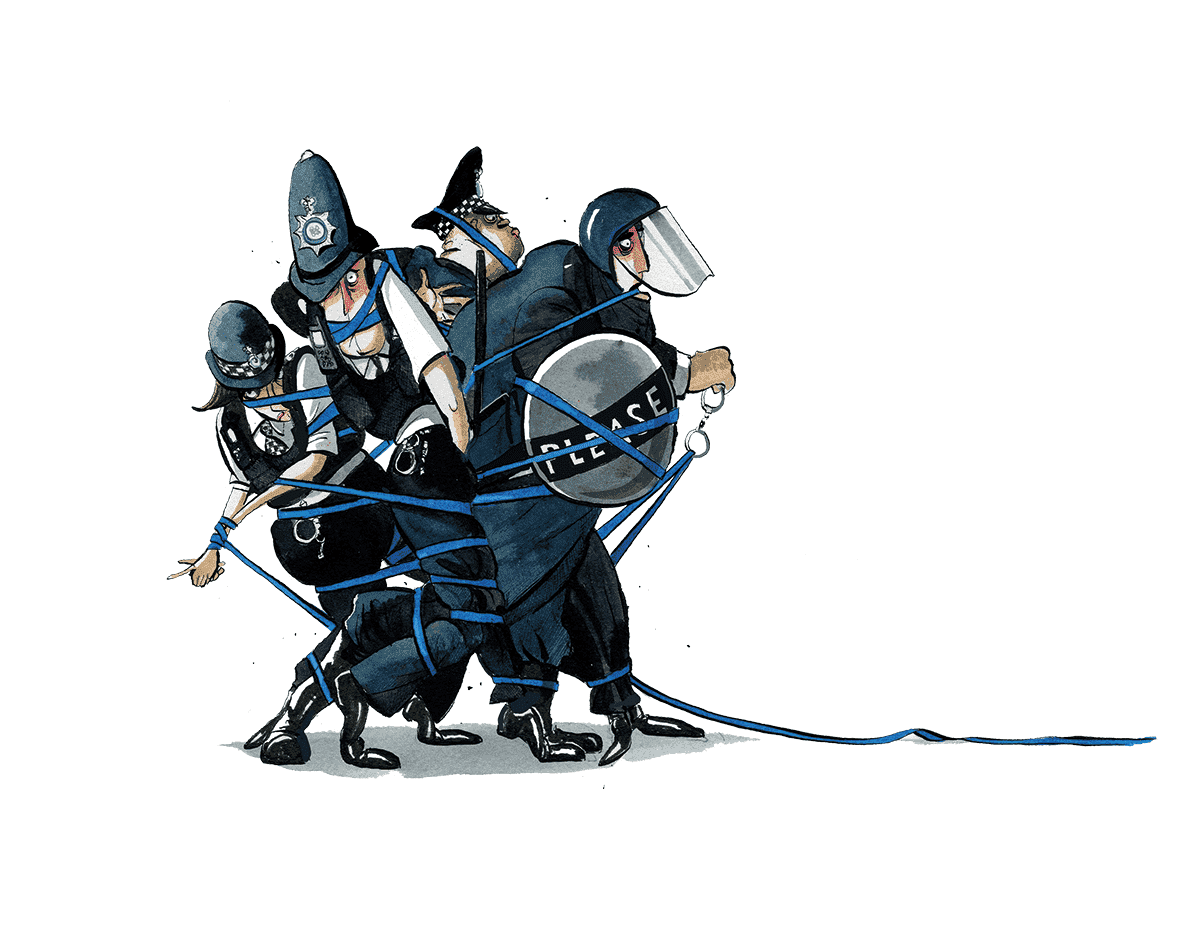

Surely, it should be obvious by now that the division of responsibility for the Metropolitan Police, between the Home Secretary and the Mayor of London, only invites discord. As does the dual role of the Met, as a quasi-national police force and the force whose job it is also to keep Londoners safe.

Among police forces in England and Wales, the Met is unique in that it is one institution, but its officers and Commissioner must serve two masters. I happen to think that Boris Johnson was right to consider the same methods of crowd control for London as are standard in many European capitals. I also happen to think that if the elected mayor is responsible, as he is, for the policing of the capital, the choice of who heads the London police belongs squarely at City Hall, and the mayor should not be able to pass on, or even share, the blame for mistakes.

The government probably has too much on its plate just now, what with inflation, the cost of living, NHS waiting lists, and the war in Ukraine, even to think about restructuring the Met, or – even better – overhauling the whole way the police service in England and Wales is organised. But the lines of any reform should be clear.

It is high time that England and Wales, if not the whole of the UK, had a genuinely national police force on the one hand, and a separate service responsible for day-to-day local policing on the other. The national force would have responsibility for dealing with the most serious crimes, including terrorism, other major investigations and all large-scale and international financial crime. Organised crime is currently the preserve of no fewer than three different agencies, including the City of London Police and the Serious Fraud Office and the National Crime Agency, and we wonder why we haven’t cracked money laundering.

This is how most European countries and even the United States organise themselves, and we should follow suit. With so much serious crime now having a national and international aspect, it is absurd that the closest England and Wales come to having a centralised police force is when the Met is summoned to help out one of the 43 regional police forces after a particularly heinous crime (the Soham murders in Cambridgeshire, or the Skripal poisonings in Salisbury).

The rising tide of public dissatisfaction, especially in London, and the scandalously low clear-up rate for so many crimes should be treated as an opportunity to look at structures and lines of responsibility again.

P.S. Let me add a personal footnote. I live within a ten minutes walk of parliament. Quite rightly, there are dozens of officers stationed in and around its precinct, and the same for Whitehall. They come out in impressive numbers to police protests, with their vans lining every side street. But the impression of plenty of police is deceptive.

The residential streets in the area must be among the least patrolled of any in the capital. Neighbourhood officers are few and far between, after all, there are plenty of police around, aren’t there? But the officers who are on duty are not there to police drug dealing or muggings or anti-social behaviour or shop theft. They are not there for us. Something similar can be sensed – though perhaps less acutely – in many parts of London, where the majority of police stations have closed. And it is one of the first things that anyone who is serious about improving not just the image, but the actual performance of the Met, has to change. Separating national from local policing duties would be a start.

Comments