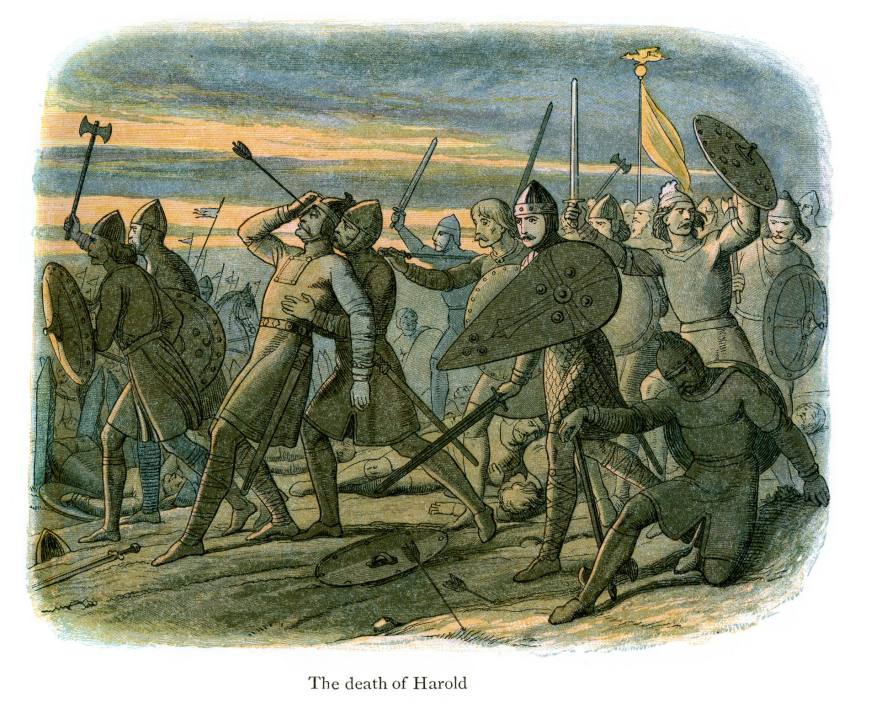

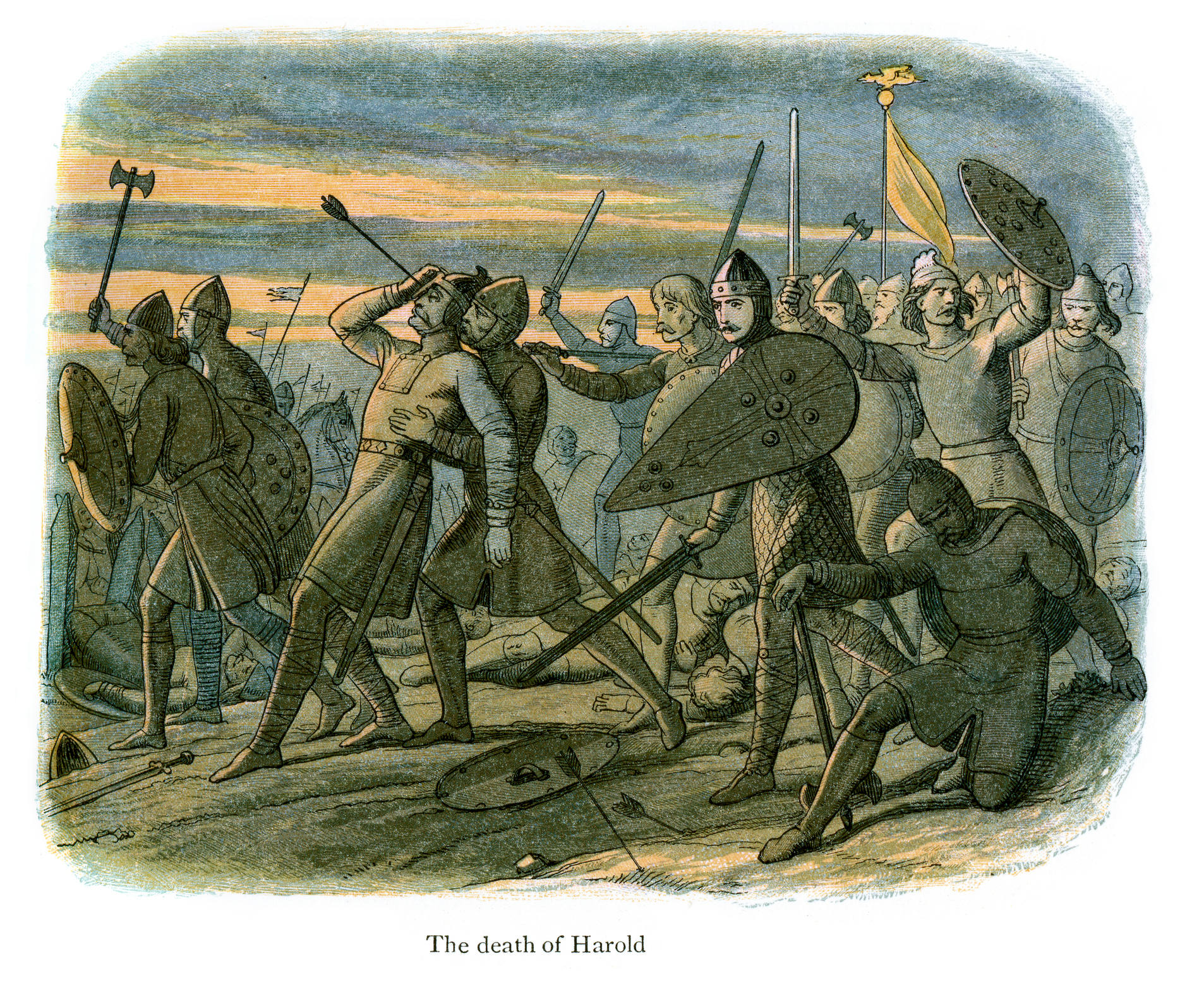

For a certain kind of amateur historian there is a moment, fixed in the imagination, endlessly revisited: it is still not yet late on that bright October afternoon in 1066, the shield-wall locked and braced, the hill still theirs, the horses floundering on the slope below, Harold upright, the sun sinking but not yet gone, the field not yet lost. You can stop it there if you wish: it is all still possible, still unspoiled, the arrow not yet loosed, the shadow not yet crossing the light. England unbroken, the language uncorrupted. All of it, still possible. And then – a shadow descends from the blue sky.

Nearly a millennium later, the Normans are back in the spotlight. The BBC’s King & Conqueror, airing today, promises a Game of Thrones-style Hastings, with James Norton as Harold and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as William. But why does England keep returning to that October afternoon, to the moment Harold fell?

For centuries the conquest has been told as disaster: the English broken on a hill, their ancient liberties snuffed out in the dusk. But that story only holds if you believe there was ever a native England to betray

At a reception this month to mark the Bayeux Tapestry’s forthcoming loan to the British Museum, Norton assured Emmanuel Macron that the Normans would be given a fair hearing. That an actor should feel obliged to placate a president about a battle fought in 1066 says everything about how contested the battle and its aftermath still is.

For centuries the conquest has been told as disaster: the English broken on a hill, their ancient liberties snuffed out in the dusk. But that story only holds if you believe there was ever a native England to betray. In truth the Normans were no more foreign than the Danes who had already taken the throne: Cnut and his sons ruled England for nearly 30 years in the early eleventh century. Edward the Confessor – son of a Norman mother, raised in exile across the Channel, speaking French at court and reliant on Norman advisers – was as much a product of Normandy as of Wessex. Harold Godwinson, who succeeded him, was half-Danish through his mother.

A ‘native’ England was never more than a retrospective fantasy, conjured after the fact – embroidered, quite literally, in the Bayeux Tapestry. Edward the Confessor was canonised in the twelfth century, and in the thirteenth his cult was enthroned at Westminster when Henry III rebuilt the abbey and translated the saint’s remains. When Henry named his son ‘Edward’, he was reaching back to that pre-Conquest past, stitching the Plantagenets into a lineage that could pretend to have survived Hastings intact.

After the Reformation the Saxons were pressed into new service: they became the image of an England before Rome, before Normandy, before the fall. Henry VIII’s propagandists cast his break with the Pope not as revolution but as restoration, a return to the freedoms of a church that had supposedly been native and uncorrupted before 1066.

By the seventeenth century the Conquest had become political ammunition. Radicals spoke of the ‘Norman yoke’, the idea that 1066 had shackled a once-free people under lords and landlords. The Levellers invoked it to claim the ancient rights of ‘free-born Englishmen’. Gerrard Winstanley, leader of the Diggers, went further: the land itself had been stolen in 1066, and must be restored to common ownership. To him the Civil War was not a revolution but the undoing of a centuries-old theft – the chance to set England ‘free from the slavery of the Norman conquest.’

Later centuries re-embroidered the story to suit their own needs. Walter Scott turned it into medieval costume drama: Ivanhoe fixed in the popular imagination a struggle of noble Saxons against villainous Normans, a romance that had little to do with the sources but everything to do with nineteenth-century nationalism. The Victorians adopted it as providence – a conquest that could be made to look like destiny. Across the Atlantic the same grammar of noble defeat was repurposed again, shaping the ‘Lost Cause’ myth of the Confederacy, where catastrophe was rewritten as chivalry betrayed – with consequences still poisoning politics today.

Harold’s England, like the Confederacy, survives less as history than as fantasy: defeat frozen at the moment before it curdles into loss, endlessly replayed because possibility is more consoling than truth.

But what, exactly, was lost? So-called Anglo-Saxon ‘freedom’ was less a birthright than a monopoly. On the eve of Hastings, five earls dominated the kingdom, while as much as a third of the population lived in slavery. Within 20 years of the Conquest that number had already fallen; within a century slavery had vanished. The Conquest was savage, but in this respect it carried progress in its wake.

William did not come to Hastings with soldiers alone; he carried Rome’s seal. Pope Alexander II armed him with a banner and a relic of St Peter. To us it looks like liturgical theatre, but in the eleventh century it was a thunderclap: Harold was not merely an enemy, he was an oath-breaker. William’s rage at that betrayal seems strange now, yet to contemporaries it gave his invasion a terrible certainty. This was not just conquest; it was punishment, judgement made visible in arms.

What followed was not a raid but a refounding. The Domesday Book counted the kingdom down to the last ox – a survey so complete nothing like it would be attempted again in Europe until the modern census.

The Normans brought more than administration. They brought scale, discipline, permanence. England was no longer a prize fought over but a base from which power pressed into Wales, Ireland and beyond. From Normandy their reach stretched further still – into Sicily, Antioch, Jerusalem. In Caen they raised the abbeys of Saint-Étienne and Sainte-Trinité; in Palermo the Cappella Palatina, where Byzantine mosaics blaze above Arabic arches; in Monreale and Cefalù they fused Latin, Greek and Islamic forms into a single vision. And in England, on the far edge of their empire, they built Durham – still one of Europe’s supreme architectural achievements in stone.

The legacy was not liberty preserved but a country recast: castles stamped into the landscape, cathedrals lifted skywards, a bureaucracy that reached every shire, a martial tradition that endures to this day. Harold’s fall was not the end of England but its invention: the island’s first rehearsal as something larger, harder, more entangled than it had ever imagined itself to be.

The gift was not freedom but certainty: the terrible clarity of a single crown, a single ledger, a single chain of command. It is the same clarity we still demand of politics: a straight line between promise and power. Which is why when Keir Starmer drones of duty or Jeremy Corbyn rhapsodises about justice, they are not reaching back to Saxon liberty but echoing a Norman inheritance. We are all William’s children now.

Comments