The Home Secretary has admitted a thing that has long been known to those of us without close protection officers: that in many communities, people often feel that ‘crime has no consequences’.

Her remarks this morning also acknowledged another pretty obvious fact: that the country has lost respect for the police.

Yvette Cooper’s words are strikingly overdue. The government’s own crime data for last year tells a sorry tale: in England and Wales, the proportion of crimes resulting in a charge was 5.7 per cent. An increasing number of cases are closed with no suspect identified – nearly 40 per cent. Nearly three-quarters of burglary cases are closed without an offender being held to account. With the highest ever level of shoplifting, half of those 430,000 crimes reported don’t identify a culprit. Recently on social media, the Met’s Deputy Commissioner Dame Lynne Owens intervened personally online to assist a victim of a phone robbery who had located her stolen mobile in a phone shop, but was unable to get local police to take any interest.

And then things begins to spiral. People, particularly in poor neighbourhoods, simply don’t report crime because they know nothing will be done about it. That in turn fuels more criminal impunity that damages community morale even more. Is it a surprise that Cleveland constabulary, the seat of some of the most vicious rioting, also has the highest level of shoplifting? It shouldn’t be.

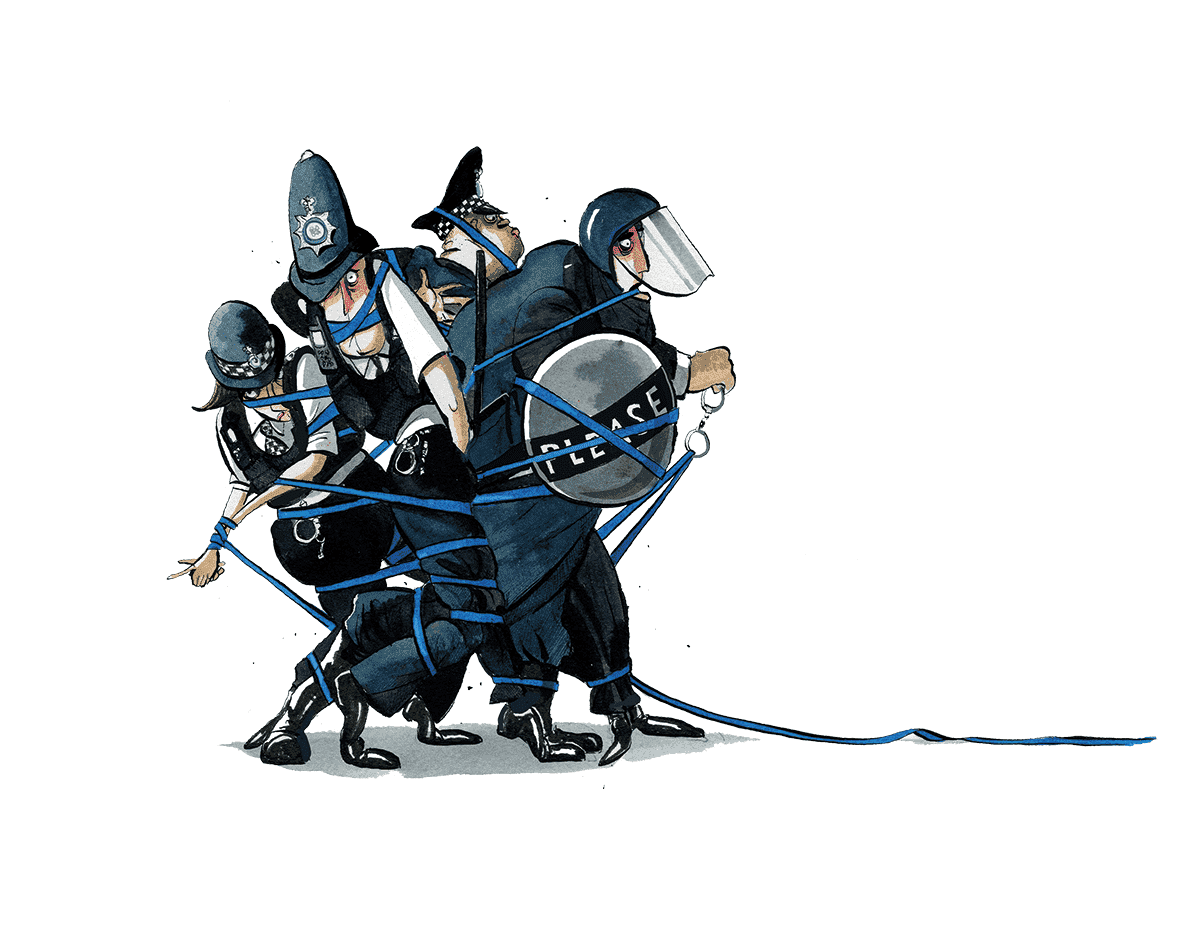

Policing these areas is such a thankless task. There are simply not enough cops to provide an effective neighbourhood presence, let alone to respond to disturbances. It’s pretty clear that police who withdrew from Harehills rioting in Leeds involving the Roma community – the cause celebre of the far right – did so not because of political pressure but simply because they were totally outnumbered and unprepared. That same pressure meant a few weeks later that cops, battered on the front line outside a Holiday Inn in Rotherham, could not contain the mob. Policing has withdrawn from communities that need it the most. It was neatly summed up by the Chief Constable of the Policer Service of Northern Ireland Jon Boucher speaking of his own force. Policing in the UK has been allowed to ‘decay’ by politicians. And here we are.

If respect for policing has declined – and all the available polling data suggests this – criminal impunity will increase. It’s important to add here that multiple scandals that have engulfed the Met, in particular Sarah Everard’s murder, have not helped. Some 47 per cent of female respondents to a BBC YouGov poll said they ‘strongly’ or ‘somewhat’ distrusted the Met, which is not surprising given they harboured a serial sexual deviant in plain sight in the ranks who went on to rape and murder.

But how does this relentless battering play out with the thousands of officers who have answered their government’s call to mobilise the Prime Ministers (barely) ‘standing army’? The officers who faced vicious assault from the very citizens they are sworn to protect? Police in Northern Ireland are used to levels of hatred so extreme that heavy armour, plastic baton rounds and water cannon are needed to separate officers from mobs armed with petrol bombs who would incinerate them if possible. Police this side of the pond were dangerously close to being overrun by people acting in a crowd who believed they were untouchable and they could say and do whatever they wanted.

So what to do? Tackling a culture of impunity and a crisis of trust requires political and operational leadership. We saw some of this in action as the criminal justice system ground a bit faster to imprison rioters and, for once, connect crime to consequence. Cynics suggested it would be great to see this alacrity demonstrated for other crime types.

But the only way to create enduring respect between police and citizens and reverse impunity is to get visible, accountable and effective police officers back into the neighbourhoods they’ve been forced to desert, where criminality has become a lifestyle choice that turns marooned communities into places decent people only want to get out of, not thrive in. These are the hard yards after the rhetoric disappears.

Comments