One influential figure on the centre-left told me recently that he isn’t bothered about who wins the Tory leadership contest. He argued that the tsunami of problems waiting to hit the new leader – rising energy prices, inflation and a creaking NHS, to name but a few – means the Tories will be in trouble regardless of whether it’s Liz Truss or Rishi Sunak who triumphs.

These issues are enough to sink any government, but especially one that has been in power for 12 years. Given how Boris Johnson dominated politics, whoever succeeds him will to some extent feel like a fresh start. But they won’t be able to pull off his trick of presenting their administration as entirely new.

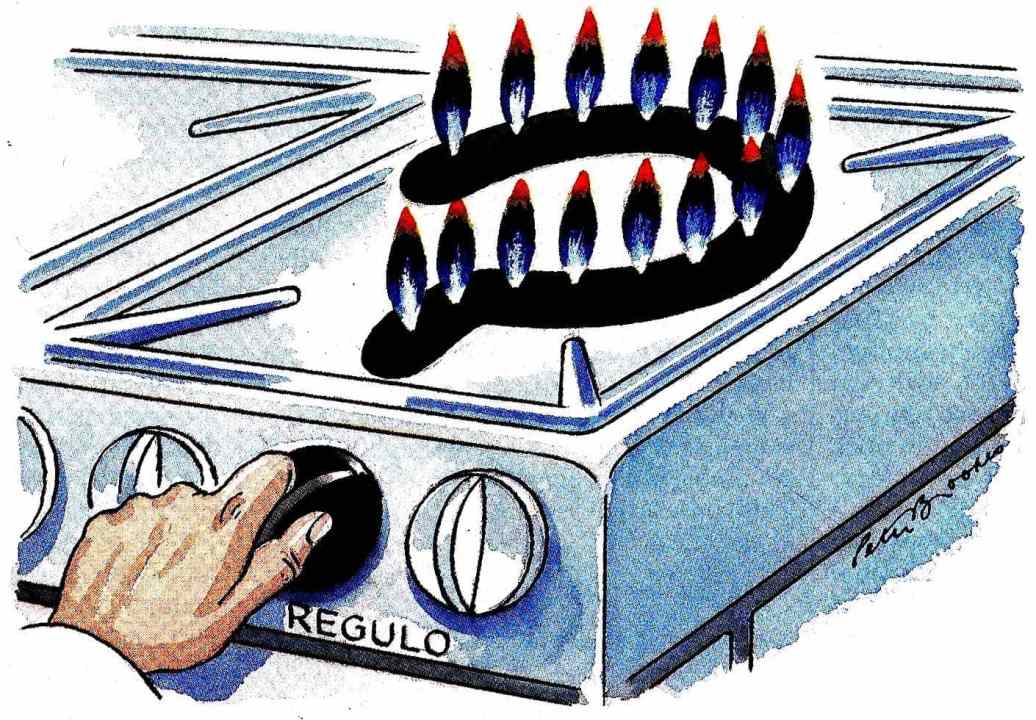

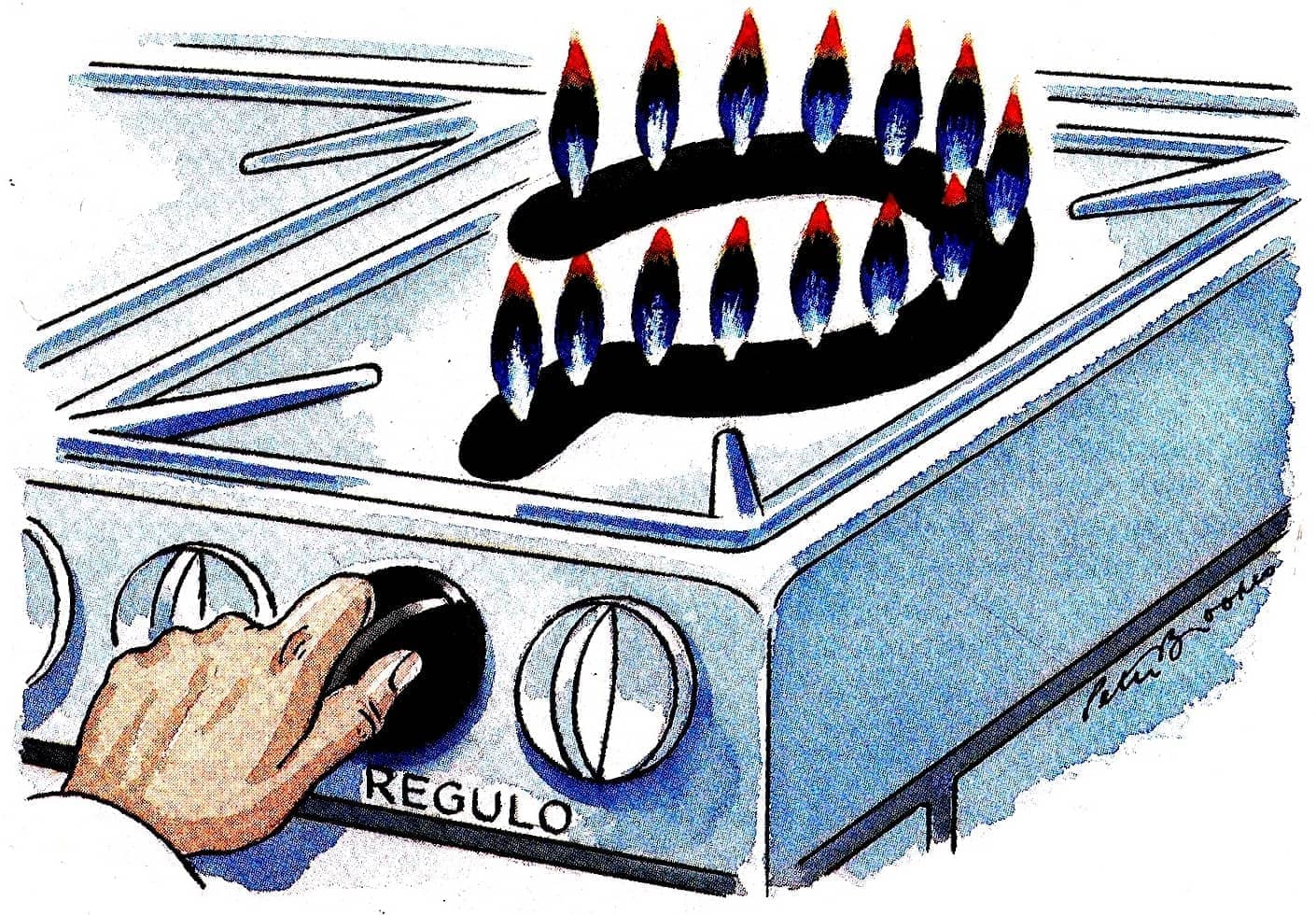

This is a particular problem for the party as mistakes made, or things not done, since 2010 have compounded the looming energy crisis. It was clearly an error to let the UK’s gas storage run down: Centrica shut the Rough storage site off the Yorkshire coast – which once accounted for 70 per cent of Britain’s natural gas storage capacity – in 2017. It was deemed too expensive to maintain and the government wasn’t prepared to support keeping it open. The belief that it would always be possible to buy gas on the spot overlooked the potential for market shocks.

It was also an error not to ensure that the UK’s power grid infrastructure was upgraded. If there are blackouts this winter it will be, in part, because of congestion on the grid. And it was a terrible mistake not to take action to deal with the fact that much of the UK’s nuclear energy was coming offline; Hinkley Point B, which provided 3 per cent of the UK’s power, was turned off just this week. Shortly before he resigned, Johnson attempted to pin the blame for the lack of nuclear planning on the last Labour government. But after more than a decade with the Conservatives in power, voters won’t want to hear such excuses from the new Tory PM.

After more than a decade with the Tories in power, voters won’t want to hear excuses from the new PM

The Tories have also worsened their own problems in this leadership contest. Their thoughts on the state’s failings have provided Keir Starmer’s Labour with its most effective attack video yet, featuring Kemi Badenoch declaring that the Tories hadn’t covered themselves in glory in their time in office, as well as clips of Sunak talking about bills going up and Truss predicting a recession.

Michael Gove might have been right when he spoke about parts of the government not working: ‘There are some core functions – giving you your passport, giving you your driving licence – which are simply, at the moment, not functioning,’ he said last month. But it’s remarkable for someone who was a Secretary of State until recently to come out with such a statement. Perhaps even more striking is that when Jacob Rees-Mogg, the minister for government efficiency, was asked this week what public service worked well in Britain, he replied: ‘Test matches are going reasonably well.’ This was obviously a joke, but it won’t inspire confidence among the electorate.

To paraphrase the American writer P.J. O’Rourke, in opposition the Tories can be the party that says government doesn’t work. But in government, they can’t be the ones to prove that. Voters won’t blame state failings on ‘the blob’ or working from home, but on the elected government.

As leader of the opposition, Starmer has operated on the principle that oppositions don’t win elections – governments lose them. He has backed away from the Corbyn-era policy prospectus, as well as many of the pledges he made in his own leadership bid, such as his commitment to common ownership of energy. Instead he’s running a small-target strategy, trying to offer the Tories as few attack lines as possible. Yet despite this, this autumn might not be the moment that the Tories lose the next election.

This is because the coming months won’t just be bad in Britain, but nearly everywhere. The public won’t look around and see this country as the sick man of Europe, but rather as one of many nations struggling to deal with the contemporary equivalent of the oil shock of the 1970s. Indeed, the UK – which relies relatively little on Russian gas (its imports make up under 5 per cent of UK gas use) – is in a better position than many other countries. In Germany, for instance, a quarter of the population is already in energy poverty. Households in Munich that cut energy use by 20 per cent will be paid a €100 bonus, and the authorities are considering setting up ‘heating havens’ where people can go to keep warm if they can’t afford to heat their homes.

It will also become clear to the public what is driving the European energy crisis: Vladimir Putin and his desire to break the West’s will to help Ukraine. This might make consumers more understanding of the situation – although however sympathetic they might be, they will still want help with their energy bills. The energy price cap is expected to rise to £3,358 a year in October and then £3,615 in January. These are huge increases considering that in April 2021, it was set at £1,138. Price rises on this scale will have an impact even on relatively prosperous households.

There’s been much talk in this contest of emergency budgets. But before a new prime minister can do anything else, he or she must work out how they are going to help consumers handle their bills. Sunak, whom I have been friends with for years, announced in May a £15 billion package of support, worth up to £1,200 for the most needy households. Yet given the current increases are considerably larger than expected back then, there will have to be significant further help – something both candidates have acknowledged. It will eat significantly into the supposed £30 billion of headroom in the public finances. The need to help households with their bills will limit the government’s room for manoeuvre elsewhere.

This autumn and winter will test countries across Europe. Beliefs that voters have taken for granted for decades, such as that there’ll always be enough energy to meet our needs, will be shaken. The challenge for the incoming prime minister will be to steer Britain through this crisis and ensure that the government can deliver what’s needed during this painful period.

Comments