One of the arguments made against leaving the EU was that Brexit Britain would have to subordinate everything in its foreign policy to economics and the need for trade deals. But the UK’s approach to China in recent months shows that this hasn’t turned out to be the case, as I say in the magazine this week.

On Tuesday, the government – in conjunction with Canada – announced measures to try and ensure that no products made using the forced labour of Uyghur Muslims end up in UK supply chains. Whitehall fully expects some kind of retaliatory response from China to this – just look at how Australia has been treated for saying there needs to be an independent inquiry into the origins of coronavirus – but went ahead anyway.

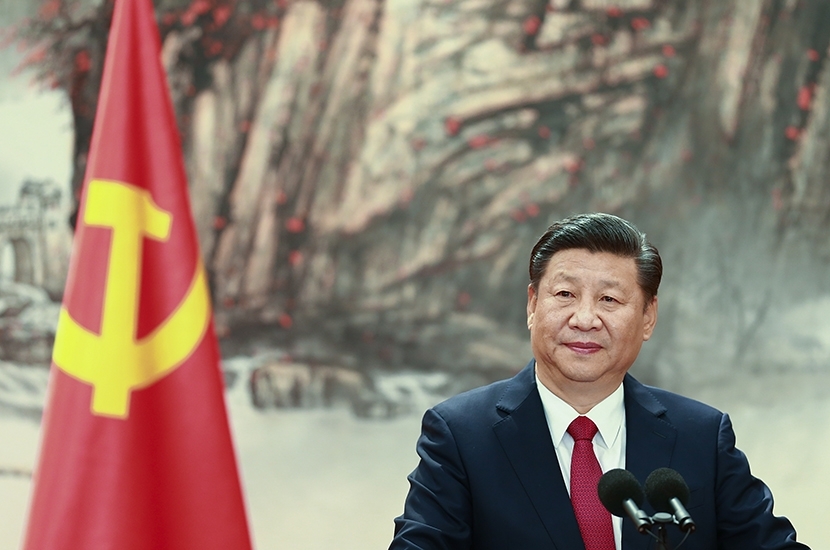

The toughening of the UK’s position on China is designed to send a message to the incoming administration in Washington: the UK will put principles before profit even at the expense of the inevitable economic retaliation from Beijing. The EU, meanwhile, is still pursuing a David Cameron-style policy of seeking Chinese investment. Look, for instance, at its recent economic treaty with Beijing (a policy which, ironically, Britain encouraged while it was an EU member state). One cabinet minister tells me the EU deal with Beijing, heavily pushed by the Germans during their presidency of the EU Council, ‘shows the EU isn’t going in the same direction as us on China’ and remarks that it’ll be ‘interesting to see what the Biden administration thinks about that’.

Some hawks in government want to go even further. One tells me: ‘The big pitch to Biden should be to break the Chinese domination in tech. We need to move these companies out of China.’ Interestingly — and in contrast to the Trump administration — the primary motivation isn’t to bring this manufacturing back to the West, but simply to shift it out of China. This will likely require an alternative mass manufacturing hub in Asia.

In the years ahead, Britain will need strong relations with the US, the EU, like-minded powers such as Canada and Australia, and the Asian democracies. Having left the EU, and the protection that being a member of a large bloc affords, the UK has a particular need for the current threats to the liberal rules-based order to be overcome. That can only happen if all these groups work together.

Comments