Over my quarter-of-a-century of being a doctor, I have overseen thousands of deaths. For a busy hospital physician, this is not an unusual number. Helping people die is a core part of our job.

In the Commons today, the Assisted Dying Bill gets its first reading. But the debate about this bill is missing a crucial detail: assisted dying is already something of a reality. For those in unsalvageable agony, I like to think it happens almost automatically. Neither people, nor the NHS, being perfect, there will be errors and omissions. But I’m confident that assisted dying, in a sense, happens often already, and I speak from experience.

As junior doctors we were taught that we had the power to kill

Hospital is the most common place of death. When the end comes, its preceding indignities and inconveniences, its terrors and agonies, are more than familiar to me. Working in a wedding florists, perhaps, or an exuberantly joyous restaurant – somewhere people went out of happiness rather than necessity – would have made for a different life. As it is, my experience of death is extensive and new legislation to support assisted dying would, in my view, be a terrible mistake.

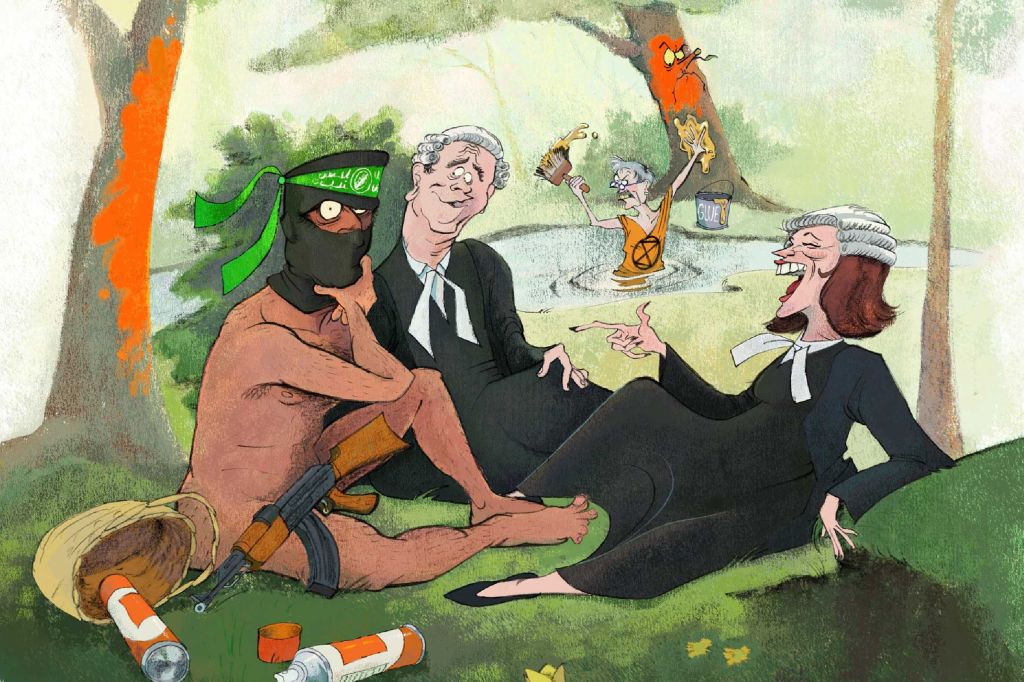

As junior doctors, we were taught that we had the power to kill. Not merely the technical ability, not only the moral and legal right, but often the duty. The doctrine of double effect holds it perfectly acceptable to cause someone’s death if you are doing it in order to relieve their pain. If I dose someone with morphine because they’re distressed, but in the full knowledge it may hasten their death, I act legally. My decision is subjective. I have no forms to fill in, no hoops to jump through, no supervisor to ask. If you suspect that I am deliberately describing my powers in such a way as to suggest that they are open to abuse, you are correct. I am doing so because it is useful to remember that powers always are.

Arguments justifying new laws for assisted dying tell stories – true and awful stories – of people tortured by suffering without any prospect of merciful release, at an apt time, via a fatal dose of medication. Perhaps their misery is that of decay, and not of pain. To decline into a state where one reasonably wishes to die, but is unable to commit suicide or to find anyone to help, is a horror. As, of course, is ending your life early because you feel that you are a burden, because you are depressed, or because you are nudged into feeling you should do so. About six thousand people kill themselves each year in the UK. Legislation to make assisted dying easier risks raising that number.

The problem, which does not get spoken of enough, is that no perfect solution exists when it comes to assisted dying; there is no system to help in one direction, without harming in the other. That people are willing to flex and break laws should never leave our mind. We should not forget that it happens now any more than we should pretend it will not continue.

Many poisons grow in our gardens or are sold in our shops. There are books and articles on how to end one’s life. I am not being coy in refraining from giving examples. It is wise not to publicise such things. Better that the barrier of effort keeps them from becoming too easy to find. Making something easier, even a little, has consequences.

Consider that minor irritation of modern life, the frustrating limit on how much paracetamol you are allowed to buy at one time. An intrusive bit of nanny-state public health policy, yes; but this rule has also likely cut the number of deaths from paracetamol poisoning. Even small changes have real impacts. Install railings on high bridges and it seems probable to assume that fewer people will jump to their deaths (nor do they necessarily go and find other methods: instead, they live). Making something even very slightly easier has serious consequences. If this bill becomes law, and we make assisted dying an option, we are introducing a change that is far more powerful than we may realise.

All effective interventions, we teach medical students, have side effects. The question is not whether a drug or a surgery or a piece of public health policy does good or harm; the question is whether it does more good than harm. Making euthanasia simpler and more available would undoubtedly save some people from awful misery and appalling deaths. The question is not whether it would have benefits, the question is what it would do overall.

In a long career of hospital medicine (about general practice, I cannot speak), I have never yet cared for someone who needed the help of this proposed legislation, someone with the judicious and irreversible desire to kill themselves, who was both unable to do so without help, yet free of the pain and distress that might allow me to act on their behalf. These people exist, and their suffering is terrible, but I do not believe they are many. Daily, however, I care for those who are depressed or suicidal, those whose spirits and hopes have faltered, those worried about being a waste of space or a burden on others. Even putting aside what it might do to relations between doctors and patients, legislation to make assisted dying easier would help some, but imperil many.

Comments