The origins of the tea’s name (spelled twanky on its first appearance in print in 1840), are as obscure as Chinese geography was then. It was attributed to a dialect version of two streams, a town or a region. In the pantomimic context it is notable that Twankay was Chinese in character, although in (the French version of) the tale from the Arabian Nights from which it derives, all the characters have Arabic names. Aladdin means ‘nobility of the faith’, the faith in question being Islam.

Twankey was easily taken up as a silly name in English because it fitted in with words such as twankydillo, used in folk songs as a refrain. The Oxford English Dictionary records twangdillo from the late 18th century as ‘the twanging of a stringed instrument’. But a song, ‘Jolly Roger Twangdillo of Plowden Hill’, appeared in a collection of earlier ballads published in 1723 by Ambrose Philips, the lampooned rival of Alexander Pope. (Philips gave rise to the term namby-pamby, used satirically of him by the witty Henry Carey, who mocked his dainty poems dedicated to the children of aristocratic patrons: ‘Namby-Pamby, pilly-piss,/ Rhimy-pim’d on Missy Miss.’) The fact is that Twangdillo suited Jolly Roger as a name because, so the great independent historian of slang Eric Partridge knew, twang was a common cant word in the 18th century, equivalent to the modern bonk.

In a song by John Gay, the author of The Beggar’s Opera, the refrain is not twankydillo but twinkum-twankum. This reminds me of that strange backwater of English law, free-bench, or in Anglo-Norman franc banc or frank bank. It was an entitlement by a widow to hold for life the property of her late husband. But in the manors of Torr in Devon or Enborne in Berkshire, if a copyhold tenant’s widow was found in an illicit liaison, she forfeited the estate unless she rode into the court of the manor backwards on a black ram, holding its tail and declaring: ‘Here I am, Riding upon a Black Ram,/ Like a Whore as I am./ And for my Crincum Crancum/ Have lost my Binkum Bankum.’ Binkum bankum referred to the bench free, and crinkum-crankum (the usual spelling) meant a thing full of twists and turns, or, more often, the pudenda muliebria, as we used to call them.

What I’m getting round to is that words in English beginning tw– are likely to be silly, and frequently low. That is why we (you and I) thought, when we first heard of people tweeting on Twitter, that it sounded daft. A bird’s tweet is also called a twit (as Eliot put it, as commalessly as Hemingway: ‘Twit twit twit Jug jug jug jug jug jug’). But a foolish twit is someone blamed or twitted, a shortened form of atwite, a word that goes back to before 1066. As David Cameron once truly remarked on the wireless, just before he became prime minister: ‘Too many tweets might make a twat.’ He apologised later for any offence caused, though he did not apologise for mispronouncing it to rhyme with cat instead of cot. What do they teach them at Eton?

Fundamentally Mr Cameron was right. Twittle-twattle is historically nothing but nonsense or twaddle, the contents of a twattle-basket or chatterbox. We are so used in English to verbs going sing, sang, sung that it seems natural for nonsense words or neologisms to follow the same pattern of ablaut (as the Germans called it) or apophony (as we hardly ever call it, borrowing from the French apophonie): bink, bank; crink, crank; twink, twank; twit, twat, twot.

If someone’s a twit, he may also be a twerp. Some people think that J.R.R. Tolkien established in the Oxford English Dictionary that twerp derived from the name of T.W. Earp, a contemporary of his as an undergraduate at Exeter College, Oxford. From the end of 1918, Tolkien worked at the OED (in the cavernous neo-classical surroundings of the old Ashmolean, now the Museum of Science, next to the Sheldonian). But the words on which he laboured all began with W: from waggle to wold. His twerp contribution came later.

All he did was to write in a letter to his son Christopher in 1944 about the poet Roy Campbell (whom he likened to Strider at the Prancing Pony), living years earlier in Oxford and ‘going about with T.W. Earp, the original twerp’. But whether Earp was the eponym, or whether his name coincided with a pre-existing word, no one knows.

The original twerp? A painting of T.W. Earp by Augustus Edwin John (Picture: The artist’s estate/Bridgeman Art Library/Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

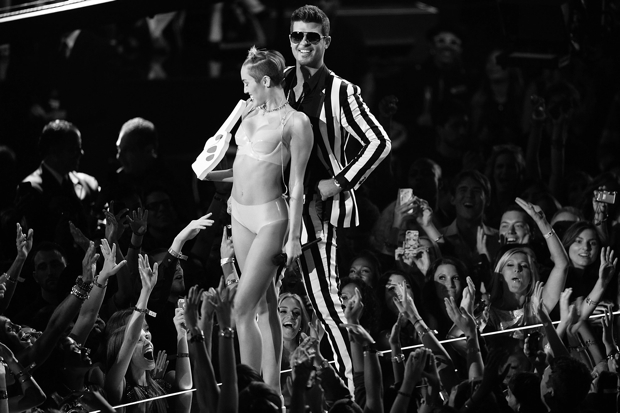

The original twerp? A painting of T.W. Earp by Augustus Edwin John (Picture: The artist’s estate/Bridgeman Art Library/Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)Which brings us to the bottom line, as it were: the lewd way of dancing expressed by the verb twerk. Like most people, I’d never heard of it before the reports of Miley Cyrus twerking away with Robin Thicke at the MTV awards this year. The OED online (the word not having made it into the dictionary itself) suggested that a ‘squatting stance’ was essential, but earlier usage, without the benefit of Mr Thicke, focuses on wobbling the bottom.

The best guess of its origin is as an alteration of work. It might have been spelled twirk (like shirk, itself also written sherk and shurk in the 17th century). There was a word twirk already, in the works of that marvellous man Nicholas Breton, the Elizabethan author of Fantasticks. It comes in his less entertaining pamphlet called The Praise of Vertuous Ladies (1599), which Miss Cyrus might read with profit. Are women more wanton than men, Breton asks. No: ‘We should finde a young man as wanton in looking Babies in a Ladies eyes as her with flirting him on the Lippes with her little Finger.’ And then, ‘If shee have her hand on the Pitte in her Cheeke, he is twyrking of his Mustachios.’ But the OED, finding the word nowhere else, guesses it might be a misprint for twirl. I’d be glad to hear if anyone has found an example elsewhere.

In any case, twerk has been around since the 1990s, all of Miss Cyrus’s conscious life. I fear she will be associated with it for however long remains to her. Twerk meanwhile takes its place between tweedledum and twitchety, in the louche society of twankers and twiddlers, twinks and twizzlers.

Comments