It is ironic that Ukip – a party obsessed with a supranational institution – is mostly likely to gain its first taste of power in local government. Following last week’s elections they have an additional 161 councillors in England with concentrations of numbers in former strongholds of both Labour and the Conservatives.

The party’s path to local leadership will be tough as the electoral cycle is not in its favour. Most of the councils where they have new strength will not vote again for three years and those that do have more regular elections tend to elect on thirds, making for slow progress.

Nonetheless, it would take a brave psephologist to rule out the idea of a Ukip or Ukip-led coalition council somewhere in the country by 2016. For example, If Labour win power nationally, their vote will probably decline in subsequent local elections, and they will suffer at Ukip’s hands in places like Rotherham and Oldham. If the Conservatives remain in charge, the voters might wish to punish the government in areas like Basildon or Southend in Essex.

The transition from protest party to executive power can be extraordinarily difficult: look at the Greens in Brighton. So what should Ukip be doing to get ready?

The main thing is for the party to decide whether it really wants power at all. Ukip has a ‘no whip’ policy and its local government spokesman has said that his councillors should be ‘independents on steroids’. This is supplemented by plans for local referendums on practically all major local decisions.

This kind of direct democracy may be tempting to offer as a party of opposition, threatening the current establishment. But it will make forming a stable administration quite difficult. This is a problem, because any Ukip council leader will soon realise that their real job is to administer cuts to their budget over which they have little control. Larger councils face perhaps a 30-40 per cent budget reduction from central government after next year’s general election.

Ukip council groups will need to be able to agree and stick to plans to cut back valued local services such as leisure centres, parks and theatres while also piling money into statutory services for the ageing. They will rapidly discover that the best way to develop their income is to allow precisely the major housing developments and out of town shopping centres that they may previously have opposed and may well lose local referenda on.

This kind of pressure would divide even some well-whipped and firmly established council groups. If they cannot impose discipline on their members, then the kippers could fall apart under the strain.

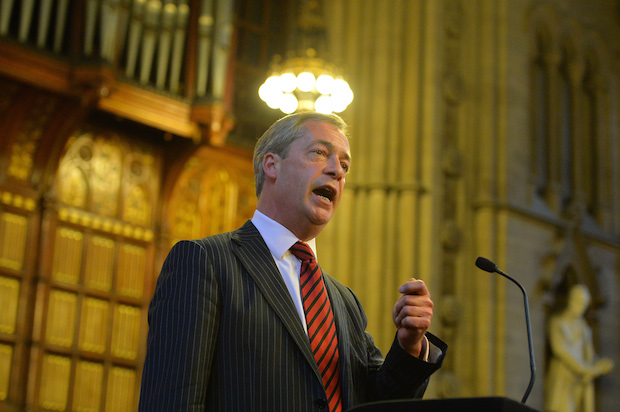

Nigel Farage’s proposals for making local savings amount to the usual call to cracking down on bureaucracy. But after four years of austerity, there is not a lot of fat left to be cut. Sacking chief executives will not fill a projected £14.5bn budget gap for England’s councils. Ukip needs a better plan.

The party will also have to reach an accommodation with the limited powers afforded to English local government. Councils cannot do much about immigration or the EU and, despite a certain amount of localism from the coalition government, they still labour under numerous inspections and well over 1,000 statutory duties to deliver everything from care homes to libraries.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of all will be the fact that leading a council often drives even the most radical protest candidate into fits of establishment-style respectability. Local government is there to fill in potholes and take care of old ladies. What happens when the party of cheeky saloon bar rebels takes responsibility for bogs and bins will be the biggest test of UKIP’s viability as a long term political force.

Simon Park is the director of the New Local Government Network

Comments