Yarnton, Oxfordshire. A teenage girl is dumped face down in a pit, her legs bent and tethered. Around her lie the crania, jawbones and ribs of several children. Taken alone, this scene of 9th-century carnage puzzles as much as it horrifies. When placed in the wider context of a seemingly universal need to ensure that the dead stay in their graves, it’s highly suggestive.

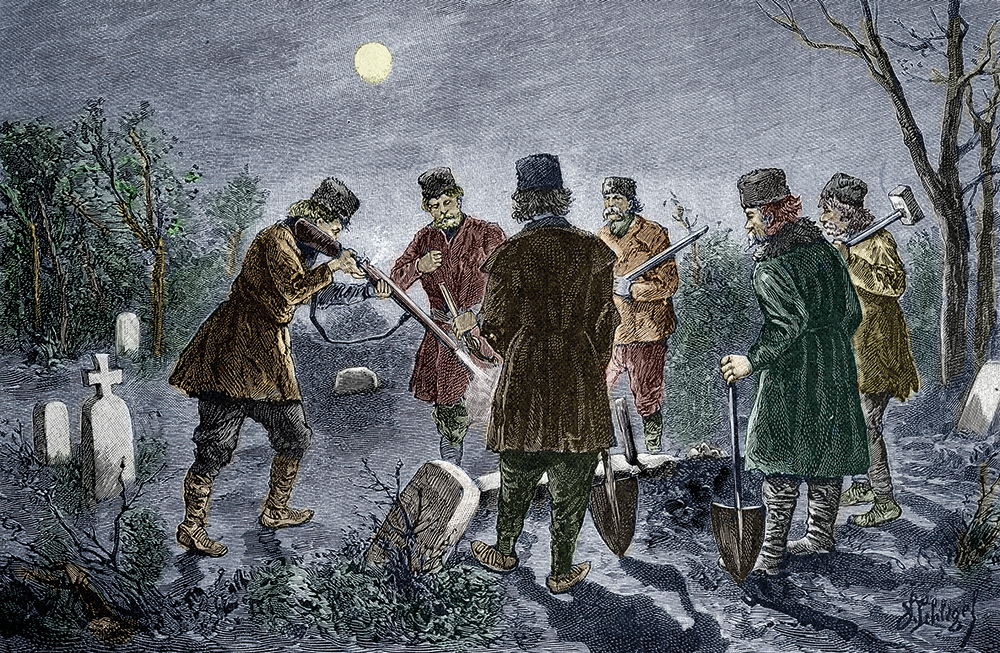

The subtitle of the medieval historian John Blair’s Killing the Dead is a tease, since vampire fiction is almost an afterthought. Folklore and imaginative literature are carefully separated from archaeological evidence. Rather than flamboyant bloodsuckers, Blair’s subject is the widespread activity of ‘corpse-killing’: bodies that needed to be further mutilated (sometimes considerably after burial) or ritually rendered harmless. Around 70 exhumations were recorded in New England in the space of a century. ‘Between 1784 and 1892, consumption-wracked families blamed the disease on the still-active internal organs of dead relatives, and took appropriate action.’

‘Since corpses do not in reality climb out of their graves and walk around, or become bloated with the blood of living victims,’ Blair states with typical coolness, ‘the question remains why people sometimes think that they do.’ His survey ranges over millennia, taking in anthropology, archaeology and the new discipline of archaeothanatology, which aims to ‘establish a theoretical and methodological framework for recording and interpreting excavated human remains’. But he has reservations: ‘The discipline seems to entertain no possibility of dead-killing activities.’ While historians of ritual need to respect scientific evidence, ‘scientists should also recognise that actions driven by belief and fear did actually take place and left material outcomes’.

The book provides many examples of such ‘outcomes’, with artists’ impressions of interments and detailed plans of excavations. Decapitation regularly occurs, sometimes – as in films – with a spade, but often with the head being wrenched off once decomposition has set in. Jawbones are severed and placed elsewhere in the grave. Damage to the left side of ribs indicate removal of the heart, which is sometimes, according to records, burnt and eaten by the revenant’s victims.

One myth that Blair is keen to quash is that vampires (broadly defined) are a Slavic construct. He maps a wide ‘vampire belt’ of post-1600 attitudes to the dangerous dead, ranging from Iceland to south-east Asia, and bordered to the north-east by regions with a strong background of shamanic belief. Marshalling the evidence over swathes of time and distance, he identifies the circumstances that push very different cultures into epidemics of corpse-killing.

Why would your kindly granny become a monster, post mortem, bent on harming you?

He probes the intriguing inconsistencies in this belief system. Why would your kindly granny become a monster, post mortem, bent on harming you? Do the dead walk in corporeal or spiritual form? Why are clearly high-status women targeted for mutilation? Why is St Cuthbert’s miraculously preserved corpse proof of sainthood when a similarly intact corpse is suspected of being under demonic control? Above all, what’s so threatening about young women and children, surely the most blameless and harmless members of a patriarchal society?

Despite Bram Stoker’s assiduous reading of the folklore, Count Dracula, Blair points out, is actually atypical; blood-drinking is more likely to be done by the living as a means of laying the unquiet corpse, and those suspected of being vampires are the recently dead, not centuries old. A literary exemplar Blair does have time for is Sheridan Le Fanu’s vampire novella Carmilla, because it captures so well the archetype of the dangerous female corpse. The status of women has fluctuated throughout history and Blair theorises that the memory of powerful queens and abbesses lingered after their decline, leaving fear and suspicion of female agency.

Among the book’s many wonderful stories, none is more startling than that of Michael Kasparek of Slovakia, who began a rampage shortly after his death in 1718. ‘He rode around on a white horse, breaking into houses and inns, eating and drinking and interrupting wedding parties.’ He also managed to make his wife and ‘four maids’ pregnant. ‘On going to bed, his victims felt something cold on their bodies, which hit, bit and strangled them. All of them had visible wounds on their hands and necks.’ Even having his ‘fresh, plump and beautiful’ corpse burnt on a pyre didn’t stop the rout. He continued to ride around insulting people, until his heart was placed in a church. Bizarre collective self-delusion and sleep paralysis is Blair’s conjecture.

Writers will no doubt continue to disinter the undead in their fiction, a recent example being Gabrielle Griffiths in her novel Greater Sins, which contains several of Blair’s motifs: a society under stress, an uncannily preserved body and the fear of female power. Let this be their handbook. Perhaps now someone will tell the tragic story of the Yarnton girl.

Comments