After one of Jeffrey Archer’s minor tangles with the absolute truth, his friend the late Barry Humphries remarked: ‘We all invent ourselves to some degree. It’s just that Jeffrey has taken it a little further than most.’

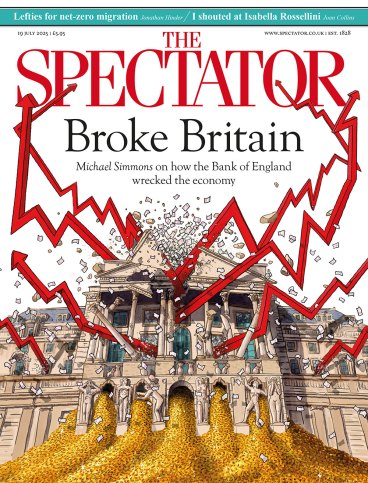

The remark came to mind last week as the media storm over the veracity (or otherwise) of the Winns’ account in The Salt Path reached its peak. As Dame Edna might have said, all travel writing is invented to some degree. It’s just that Raynor and Moth may have taken it a little further than most.

‘In Patagonia?’ Bruce Chatwin’s lodger is said to have remarked of the eponymous book. ‘I doubt Bruce even went downstairs.’ That’s unfair. Chatwin undoubtedly visited Patagonia. But accounts from others in the region itself do cast doubt on some of his reported encounters there. And I read The Songlines about his Australian travels in Aboriginal lands with increasing scepticism.

I have something here to declare. Of all my books the best-selling has been the first I ever wrote, Inca-Kola, about my travels in Peru and Bolivia. I’m proud of it, still in print after more than 30 years. But the book is the story of a single journey through the Andes. In fact my story was constructed from three distinct journeys. Everything I describe happened, even if I sometimes exaggerate a bit; but events didn’t always happen in the order in which they happen in the book.

And even where no violence is done to the narrative thread, no report can be divorced from the character, prejudices and powers of memory of the reporter. The world he describes is seen through the filter of his own attitudes, and by leaving out (which we must all do) we subtly alter the shape of what we leave in.

Between truth, truthiness and downright falsehood there’s a sliding scale

This column is not meant as an apologia for the Winns. I’m in no position to judge the truths or untruths of their story. What I do question is the existence in the genre of travel writing or journalism of any clear line between fact and fiction: any line which, once crossed, makes the author a liar. I’d go as far as to suggest that a measure of shapeshifting, of filtering in and filtering out, though built upon the real men, women and places the writer has encountered, can create a story that is in part a work of the author’s imagination. Some of the worst travel writing has been produced by a traveller’s attempt to keep a literal diary and offer a blow-by-blow report of everything that happened. Wilfred Thesiger deserves his place in the travel-writers’ hall of fame, but he’s a dreadful writer. It’s the things he did and the places he saw that elevate his journals; but he has written them up in flat, emotionless schoolboy prose that only fails to kill the story because the subject matter is so extraordinary.

The late Dervla Murphy did, on the whole, offer a day-to-day account of real travel experiences, but this sometimes deadens the writing. Her diary-making can struggle to bring to life scenes which in (say) Graham Greene’s or D.H. Lawrence’s hands would burn brightly in the reader’s imagination. Her derring-do, her pluck, her own remarkable personality, are enough to redeem her prose style but never quite to lift it into the category we’d reserve for (for instance) Patrick Leigh Fermor or Eric Newby. The former’s Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese has a luminous quality, but Leigh Fermor took his wife, and I’ve often wondered how Mrs Leigh Fermor’s account (had she offered us one) would have read. Newby’s short walk in the Hindu Kush made for a deservedly classic report but (in my experience) humour and truth make uneasy bedfellows, and I wouldn’t read Newby for a fair and insightful look at the peoples of Afghanistan. Rory Stewart makes a better fist of trying to understand, but he isn’t so funny.

I like Paul Theroux’s writing, but Theroux’s Patagonia in The Old Patagonian Express is hardly recognisable to this columnist, who has spent blithe weeks among kind and courteous people in the region, and whose memories are dominated not by skirmish and difficulty, but by the most magnificent landscapes. Like humour, disgust makes for lively writing, but may skew reality.

Were we to subject (say) Michael Palin’s or David Attenborough’s TV documentaries about our planet to the critical scrutiny that the Winns’ account of the Salt Path has met, we would encounter no personal dishonesty: but a look behind the scenes at how such documentaries are made would blow to pieces any idea that the journeys these presenters have made will have felt anything like the narrative we see on the screen.

Palin does not just happen upon every encounter filmed with the locals in remote places: camera crews, advance parties, editors’ ideas are often necessary to set up scenes that on the screen appear impromptu. And I remember Sir David telling me that the sound of migrating reindeers’ hooves in the snow is produced using custard powder and a pestle and mortar. None of us would wish Attenborough to bury himself in the snows of Lapland, but be clear, he isn’t always there.

I recall (in the last century) filming, for one of my Weekend World programmes, near a railway sidings north of King’s Cross. We had no time to travel to Liverpool for a Merseyside sequence for which this footage was presented as the backdrop, so King’s Cross had to do.

Between truth, truthiness and downright falsehood in travel journalism there’s a sliding scale. At one end lies the dullness of a mere schoolboy diary. At the other the alleged behaviour of Mr and Mrs Winn. Perhaps we should thank Raynor and Moth. First the nation was immensely moved, as we love to be moved, by the book, then the film. Then the nation revelled, as we love to revel, in the pulling down of what we had built up. The couple have delighted us twice. Can we ask more?

Comments