On 15 September 1885, the world’s most famous elephant, Jumbo, was killed by a train. Jumbo, the star attraction at P.T. Barnum’s travelling circus, was crossing the track at a station in Ontario, Canada. His handler, Matthew Scott, saw the danger. But ‘the elephant, fatally confused, trumpeted wildly and ran towards the oncoming train’. The force of the locomotive crushed Jumbo’s skull and drove one of his tusks ‘back into his brain’. But was this really an accident, or had Barnum, or Scott, or both, committed elephanticide?

When the engine hit him, Jumbo was dead within minutes. A bull African elephant is no match for a freight train. But if, for whatever reason, you needed to kill an elephant in 1885, there would be no better way than to engineer a train accident. Elephants, as John Sutherland points out, are very, very hard to kill. He gives us some examples. In 1826, an elephant called Chunee, an attraction at a London menagerie, started going wild, as bull elephants do from time to time when they reach maturity — they are subject to what Sutherland describes as a ‘storm of testosterone’. Chunee’s owner, who couldn’t live with the situation, hired two soldiers to shoot him. But the execution was a terrible mess. The soldiers lined up outside the elephant’s cage, and shot endless volleys into his thick hide. But this was not decisive. In the end, Chunee had to be stabbed to death with swords — a terrible, cruel death.

In another incident, this time in America’s Deep South, a circus elephant called Mary killed three men. After the third killing, in which she picked a man up with her trunk and flung him to the ground, she was sentenced to death by hanging. But the thing is, you can’t hang an elephant, not in the neat way you can hang a human being, anyway. ‘Elephants,’ as Sutherland tells us, ‘weren’t anatomically engineered for that kind of treatment.’ Another American-owned elephant, Topsy, was killed by electrocution. Thomas Edison, who wanted to demonstrate the dangers of the alternating current of his rival, George Westinghouse, was in on the act and even filmed the event, which sounds horrible. As the elephant died,‘smoke billowed up from her feet’, we are told.

I think I’m digressing a bit. This isn’t just a book about killing elephants; it’s a book about being horrible to elephants in more general ways. It’s very good. It’s one of those books that shows you the world through the lens of a small part of it. Sutherland’s tone throughout is one of dry wit; the track where Jumbo died, he points out, was known as ‘the grand trunk’. Sutherland makes Jumbo his main character, and shows us that by looking at this elephant’s life, and the lives of other captive elephants, you can learn a lot about people too.

Jumbo, says Sutherland, was captured by the Hamran tribe of East Africa, where ‘the killing of savannah elephants had been brought to a high art’. A horseman would approach the elephant from behind, and slice his or her leg open — by cutting the right artery, the elephant ‘bleeds out’ in an hour — there’s an awful lot of blood, although the death is, some say, painless. Anyway, Jumbo’s mother was killed in this way, and, there being a burgeoning market in exotic beasts, he was sold, via various dealers, to the menagerie at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. But he wasn’t a hit. He was depressed and ill — and very expensive to feed. So the French zoo gave him to the London Zoo in Regent’s Park, in exchange for a rhino. It was a lucky swap — the other elephants in the Jardin des Plantes ended up being eaten, even though, apparently, they tasted awful.

Sutherland’s main point might seem obvious: that trying to keep an elephant in captivity is, in every way, a bad thing. They just hate it. The only thing you can do, he explains, is break them, using whips and gaffs and pronged instruments. Jumbo, who arrived in England in a terrible state, with rotting flesh, his feet having been attacked by rats, was cleaned up. And Matthew Scott, his handler, seemed to develop an understanding with him. But at what cost? The elephant was in low spirits and self-harming: at night, he ground his tusks on the walls of his bunker. At the end of a long day, Scott and Jumbo would settle down to a boozy evening. Jumbo drank whisky, beer and even champagne. Sutherland, himself a recovering alcoholic, speculates that Jumbo might have been one too.

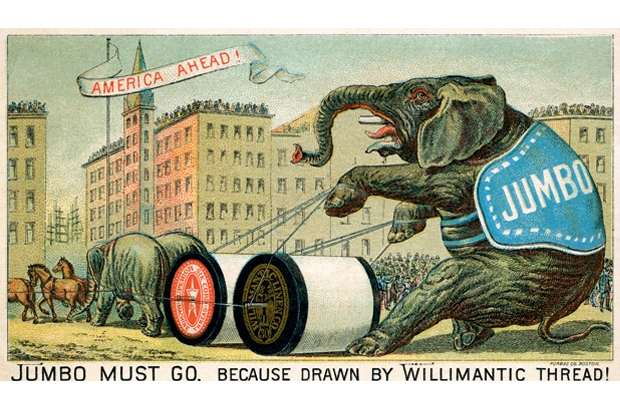

But you also see that Sutherland is making a deeper point— the elephant, so often a metaphor, is a metaphor here, too. The elephant in the room, if you like, the thing you can never quite get away from, is the idea that human beings think they can tame pretty much anything, when they can’t. During the day, Jumbo looked docile, but he was brutalised and dosed with alcohol at night. And then came the inevitable storm of testosterone, which his Victorian keepers couldn’t handle at all. That’s when they sold him to P.T. Barnum. The hard-headed Barnum liked Jumbo. And then, after a while, maybe he liked him less. It’s possible that Jumbo was more seroiusly ill than he looked; that he had become a liability.

Born in Africa, Jumbo was sold into slavery. He went to France, where he narrowly escaped being eaten; he was taken to England, where he was subdued, but where his keepers were embarrassed about his sexuality. In America he became a star and possibly a murder victim. Can all of this really have happened? It’s a tall tale. And rather superbly put together.

Comments