For a man who has only delivered two Budgets, Rishi Sunak is no stranger to fiscal announcements. Last March’s £30bn spending splurge was just the start of hundreds of billions of pounds spent in the fight against Covid-19. Today Sunak pledged another £65bn: furlough and the Universal Credit uplift were both extended; incentive payments for businesses to take on apprentices were doubled; and ‘restart grants’ worth £5bn to help businesses get back on their feet were unveiled.

But this Budget wasn’t all giveaways. The Tory Chancellor announced a new, tiered system for corporation tax, which hikes the rate from 19 per cent to 25 per cent in 2023 for the most profitable businesses. He has also frozen personal income tax thresholds: dubbed a ‘stealth tax’, this will bump workers into higher tax brackets as wages rise while the thresholds don’t.

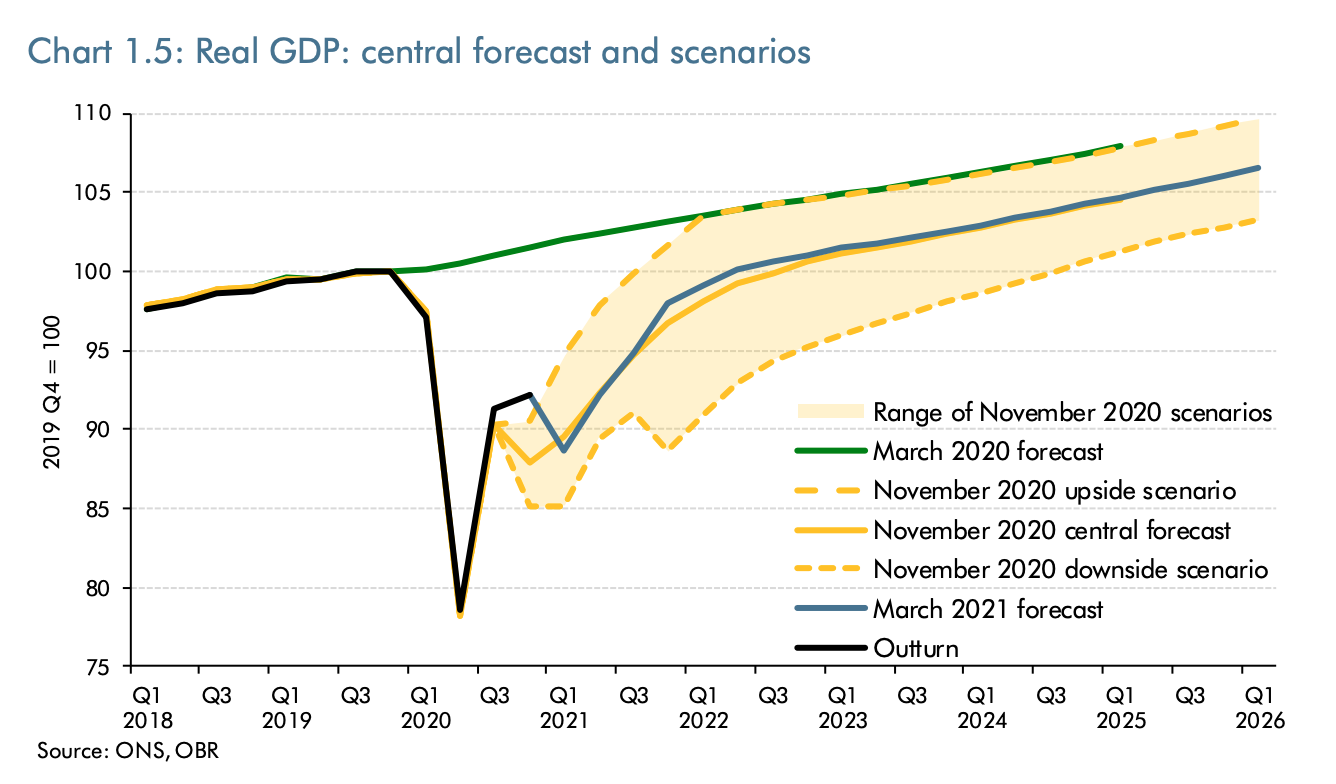

What does this mixed bag of policies mean for the UK’s economic recovery? The good news out of today’s Budget was an update from the Office for Budget Responsibility, which has moved forward its most recent forecast for GDP to return to pre-pandemic levels. This is now expected to happen in the middle of next year.

After contracting an astonishing 9.9 per cent in 2020, growth is forecast to be four per cent this year (reflecting a winter dominated by lockdown, and a summer in which restrictions are expected to be lifted), followed by a specular 7.3 per cent boom in 2022.

There are reasons to be hopeful about the UK’s growth prospects

The more problematic news, however, is that after 2022, growth rates are expected to fall back down to business as usual: hovering around a fine, but by no means impressive, 1.6 per cent rate.

As we continue to struggle through severe hits to the economy (another dip is predicted by the OBR this winter to account for the current lockdown), any positive growth figures might seem like good news. But if Sunak has plans to address the UK’s £2.8 trillion debt and sky-high deficits in the coming years without raising taxes further, it’s going to require a pro-growth agenda.

Based on today’s forecasts, the growth policies he announced (including ‘full expensing plus’ for business, which will enable them to reclaim investment expenses, with a subsidy on top), aren’t going to be anywhere near enough. After borrowing £355bn in 2020-21, the Treasury is set to borrow another £234bn – and borrowing above £100bn for the foreseeable future. While current spending can be described as ‘war-time’ spending, it’s increasingly clear the Covid crisis is not, as previously argued, a ‘one-off’ spending spree.

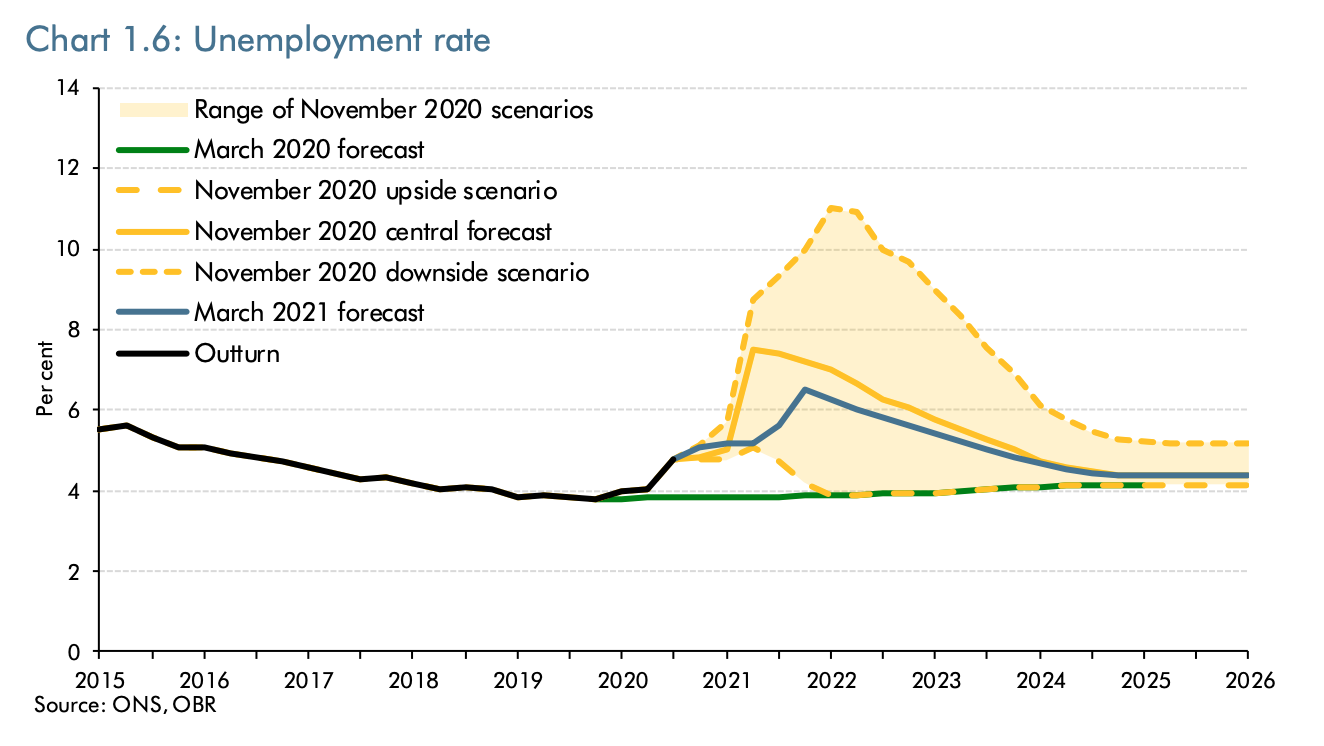

Still, there are reasons to be hopeful about the UK’s growth prospects. One of the best updates today came in the form of the latest unemployment forecasts: the OBR has dropped its initial forecast of an 11.9 per cent unemployment peak right down to 6.5 per cent.

However, the extension of the furlough scheme to the autumn – which, by the end, could see some employees having had their wages paid by the government for 18 months – suggests the Treasury is still worried about the employment revelations that will come to pass once the scheme is eventually lifted.

The reality is that when furlough lifts, many of these jobs will no longer exist. Sunak is betting that by September, a roaring summer of economic activity will have boosted GDP: conditions should be better for getting people back to work. But it’s not a bet without risks. Lingering intervention in the labour market is likely to stall the natural changes and shifts that are bound to take place after reopening. These are crucial for the economic bounce back to happen.

Today’s announcements were not designed to tackle the UK’s long-term economic prospects, but instead address two more immediate concerns: continuing to support people and business through the crisis, and getting the UK’s finances into a position to handle a small change to what is currently an extremely agreeable environment for borrowing money.

Sunak’s tax rises should be seen in this context: not to ‘pay down the debt’ which is most often referenced, but to cover servicing the debt – an area in which the Chancellor thinks the UK is vulnerable. The freeze to income tax, on its own, is estimated to raise over £19bn. This will go a long way to filling the fiscal black hole that would be created if interest rates, gilt rates or inflation crept up. The hike in corporation tax is estimated to force businesses to hand over much more to the Treasury: nearly £50bn.

On both of these counts, it would seem the Chancellor has succeeded: but his wins won’t come without costs, including the threat that a higher tax burden poses to going for growth. In this sense, it was a short-term Budget. But with the end of lockdown and Covid restrictions still months away, it was never likely to be anything more. After all, no policy or relief package can substitute for an open economy.

Comments