Rod Liddle fears he may be doomed — although the modern Church of Englandis reluctant to admit that anyone at all suffers eternal damnation

Not so long ago, when I was making a film about some aspect of Christianity for Channel 4, I asked a Church of England bishop about the concept of heaven, what it was like up there, whether or not there was a Starbucks, would we all get our own rooms and is there WiFi etc. He looked at me as if I were mad. In fact, the expression on his face was exactly the same as when I put the same question to the science writer and paradoxically committed atheist Richard Dawkins. ‘Oh, good grief… I really wouldn’t bother yourself with any of that nonsense,’ he said, after ascertaining that I had asked my question in all seriousness.

When he expanded a little on this dismissal it was to the effect that we live on in the memories of the people we have known, and through the consequences of our acts. This seemed a markedly less fun and indeed concrete version of heaven than the one I had been brought up with; in fact it seemed closer, ecumenically, to Belinda Carlisle’s exegesis on the subject ‘Heaven is a Place on Earth’, in which she assures her ‘baby’ that we are only beginning to understand the ‘miracle of living’, a theme reprised a decade or so later in similar theological fashion by Ms Britney Spears, in her declamatory anthem ‘Heaven on Earth’. Later I asked the bishop about God and he looked perplexed for a while and waggled his hand from side to side, possibly, possibly not, who the hell knows?

This is an apt time to consider heaven and what it might actually entail. Obviously, because we are celebrating Easter and that moment when Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after His crucifixion, the desolate, empty tomb subsequently discovered by his startled and suitably impressed disciples. But more pertinently for me, I have just had a complaint upheld against me by the Press Complaints Commission. In my quotidian conception of heaven, with its ledger book of reckoning between good deeds and bad, then the PCC stuff might just be the thing to swing the balance and send me hurtling downwards — at the very moment the Daily Mail’s Jan Moir is admitted. I assume God takes the PCC seriously; in fact when I think of God the vision I have in my head is not a grey-haired old gentleman, but one of those young female Liberal Democrat MPs they have on Question Time every week. I always assume that the quotidian reckoning will be on the severe side and the final verdict delivered in the strident tones of a Guardian leader page article about something Israel’s been doing.

I am not sure what the official position of the Church of England is regarding heaven; certainly it seems to be changing. And yet the change seems to have been brought about less as a consequence of scientific onslaught than a shift in the politics of the Church over the last 50 or so years; and most certainly away from the concept of heaven as a ‘reward’ for simple, pious, belief. This is a notion still held dear by many evangelical Christians, of course, the most extreme of whom believe that an very small number of people — the figures vary, but 44,000 is one I have heard mentioned quite often, a town the size, although not necessarily the disposition, of Redcar — will be taken up to the meet the Lord at some terribly glitzy function, as a consequence of their especial piety. But for mainstream Anglicans this idea has withered a little, to the sort of position advanced by Søren Kierkegaard: who knows what’s up there? Maybe nothing. Maybe something. What a mystery it all is.

The science, as always, has been appropriated by both sides; scarcely a month goes by without a new study into near death experiences, in which the bright, distant lights seen by people who have technically ‘died’ are explained as the brain running through a few final programmes before it shuts down for good. Or, conversely, that the lights cannot be explained away in such a manner, and that people who claim that during medical procedures under anaesthetic they have left their bodies lying on the operating table, floated up to the ceiling, drifted down corridors and done a little light shopping, should have these claims taken seriously. Experiments have been done to see if these people were imagining such journeys or if they ‘really’ occurred, and the results have tended to be inconclusive. The fact remains that if you tend to believe in life after death, the science is not going to demolish that faith, nor for that matter reinforce it.

My point, though, is that it is the political aspect of heaven which seems to make it less palatable to the modern Church of England, rather than a straightforward rational dismissal of what atheists would describe as far-fetched wishful thinking. The first and most important objection is that the Church of England, more than ever before, believes that its purpose and the purpose of its followers is to alleviate misery on earth right now; that while Christianity has always placed a great importance upon goodly works, fighting poverty, healing the sick and so on, this was secondary to a belief in God.

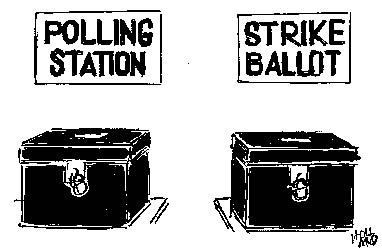

It seems that this is no longer so and that what was once a characteristic of Anglican Christianity has become almost its sole raison d’être. And there is a second political objection to heaven, which is related to the first. The Church of England loathes, perhaps more than anything else, including the devil, the notion of exclusivity. The idea that one could be allowed into heaven simply for having signed up to the correct set of laws and shibboleths is absolutely antithetical to the Church of England. It is a short step from this to the position adopted by the bishop I mentioned at the start of this article; that heaven cannot really exist at all. I suppose it is worth dying to see if they are proved wrong.

Comments